Scientist of the Day - Edmund Cartwright

Edmund Cartwright, an English cleric and inventor, died Oct. 30, 1823, at age 80. Cartwright's name is one of those that you memorize when you are learning about the Industrial Revolution in grade school, along with Richard Arkwright, John Kay, James Hargreaves, and James Watt. However, it is a rare individual who can tell Arkwright from Cartwright. If you need a hint, Cartwright was the one who loomed largest.

According to the conventional story of the progression of the textile revolution, which has a great deal of truth to it, first came the flying shuttle (Kay, 1733), then the spinning jenny (Hargreaves, 1764), then the water-frame (Arkwright, 1769), and the Watt (soon Watt-Boulton) steam engine (1775). As the thread and yarn started to pile up, what was sorely needed was a speedier way to weave cloth. Cartwright, who had recently taken holy orders, decided to tackle the problem, and in 1785, he designed his first power loom. It did not work very well, and it was only then that he saw a conventional treadle loom, and he was flabbergasted at how much better the traditional design was. So he had another go, and by 1787 he had built an improved loom, running on water power, and this time he really had something. By 1789, he had coupled his loom to a Watt and Boulton steam engine, and the revolution in textile manufacturing was off and running.

Initially there was a great deal of resistance – violent resistance – from textile workers to the power loom, and at least one manufacturer who ordered Cartwright looms had his factory burned to the ground. Cartwright did not profit much from his invention at first, and then his patents ran out, but in 1809, the British parliament granted him £10,000 for his essential contribution to the Industrial Revolution, which was a huge amount, almost comparable to the £18,750 that had been awarded to John Harrison for solving the longitude problem with his chronometer. The best part of Cartwright's story is that he was an Anglican minister as well as a textile pioneer. That means he is one of the few persons about whom you can say "he was a true man of the cloth" and have it come off as a double entendre.

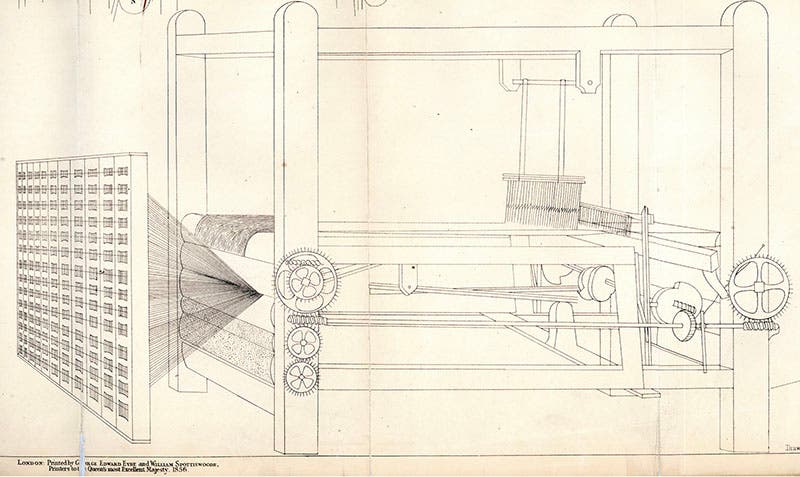

By all accounts, Cartwright’s looms had a lot of problems, and it took inventive contributions from many others to make the power loom a viable force in textile manufacturing. So it is hard to find an original Cartwright loom to illustrate his invention. The best image we have is a version of his patent application drawing (third image), redrawn later (thanks to Jeremy Norman for discovering this and including it on his History of Information website, from which we borrowed it).

Consequenly, most of the power looms preserved in textile museums are mid-19th-century or later. Still, a view of one of those historic sites, such as the Queen Street Mill in Harle Syke, about 20 miles north of Manchester, with 300 Lancashire power looms amassed under the roof of one shed, gives you a pretty good idea of why Cartwright’s invention was so impactful.

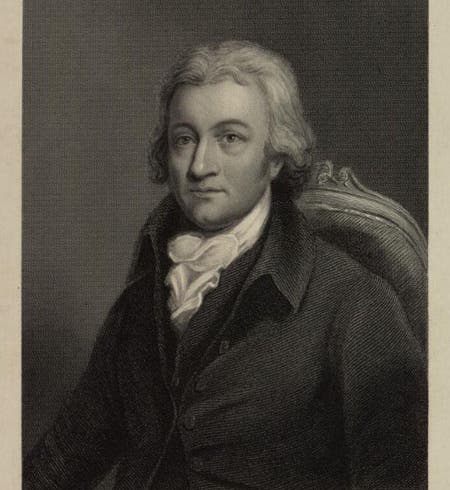

There is a stipple-engraved portrait of Cartwright at the National Library of Wales (first image). In William Walker’s ink-and-wash drawing of “Famous Men of Science in 1807-08” (before 1862), which was later engraved and preserved in the National Portrait Gallery in London, Cartwright is at far right. In the detail of the wash drawing that we show here (fourth image), he is seated right in the middle, looking to your right, between the chemists Charles Tennant (left) and James Reynolds (right), who look straight at you. You can read more about Walker’s drawing and engraving at our post on Walker.

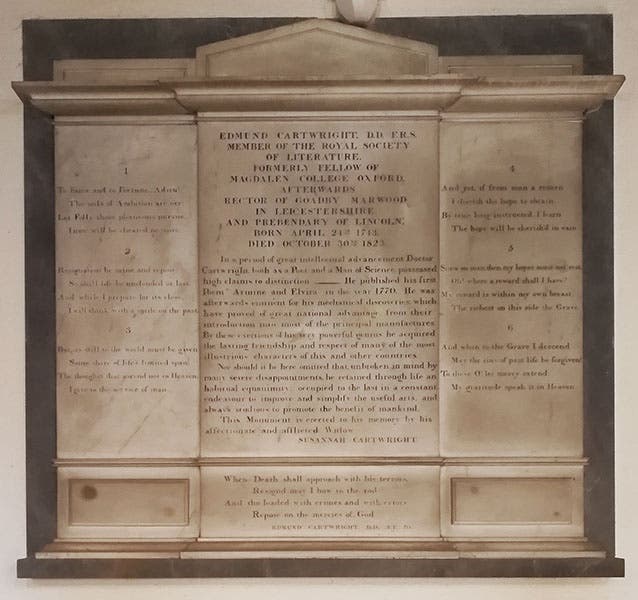

Cartwright lived out his remaining years in Hastings, East Sussex, and is buried in St. Mary-the-Virgin churchyard in Battle. There is an elaborate memorial stone for Cartwright inside the church (fifth image), which you can enlarge and read on the findagrave.com website

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.