Scientist of the Day - Othniel C. Marsh

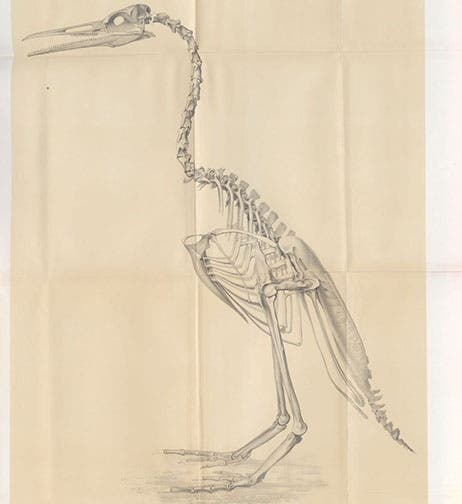

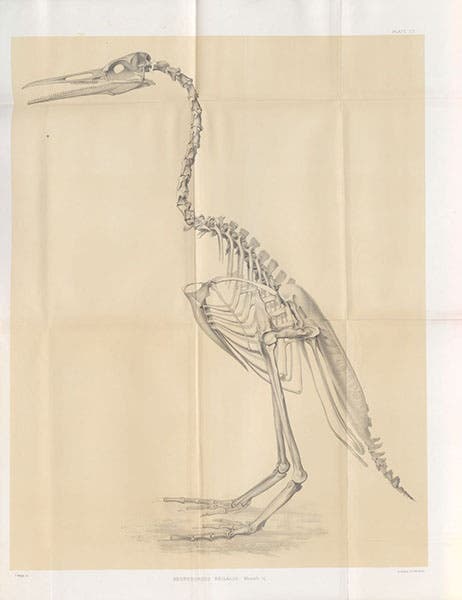

Skeletal restoration of Hesperornis regalis, a flightless bird of the Cretaceous era, named and described by O.C. Marsh, lithograph in Odontornithes: A Monograph of the Extinct Toothed Birds of North America, Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, vol. 1, pl. 20, 1880 (Linda Hall Library)

Othniel Charles Marsh, an American paleontologist, was born Oct. 29, 1831, near Lockport, N.Y. His family was poor, but thanks to a rich uncle, George Peabody, he was able to attend Phillips Academy and Yale College. He toured in Europe, saw continental museum collections, and came back ready to collect on his own. He was one of the first eastern paleontologists to look for fossils out west, which was just being opened up by the transcontinental railroad. He searchd at first on his own, then with hired bone hunters, and eventually in absentia, directing things from New Haven. His expeditions turned up such famous prehistoric beasts as Brontosaurus and Stegosaurus, and he convinced his uncle to endow a repository at Yale, the Peabody Museum of Natural History, to house his growing collection. We looked at the dinosaur side of Marsh in an earlier post in 2018.

But Marsh is also known for discovering the first Cretaceous birds in the United States, which turned out to have great significance for supporters of Darwinian evolution. Thomas H. Huxley, an active defender of Darwin, had been the first to propose that birds evolved from dinosaur-like reptiles, but he really had no evidence except Archaeopertyx, a fossil of Jurassic age found in Germany in 1861 that had a body structure similar to Compsognathus, a small dinosaur, but clearly had feathered wings. But of fossil birds that had reptilian attributes, there were none.

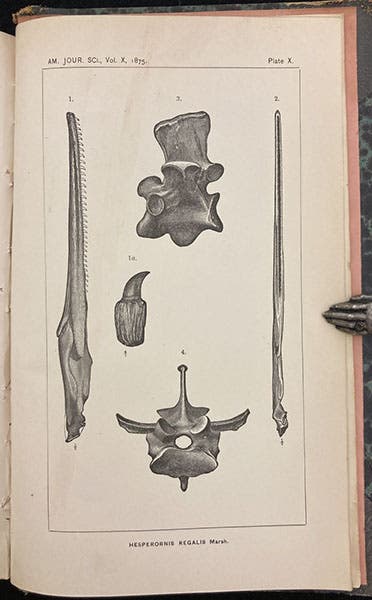

Marsh made his first trip out west with students in 1870, spending most of his time in Kansas, where he found, among many other things, a fossil foot- bone that he did not, at the time, recognize as avian. The next year, 1871, he found a partial skeleton of a flightless bird that he thought (over-enthusiastically) might have stood 5 feet tall. But the skull was missing. He named it Hesperornis regalis, the “regal western bird”. In the following year, 1872, a student of his found a more complete skeleton of Hesperornis, this time with a skull. It was virtually complete. The skull was long and thin, and it had rows of small conical teeth all along the lower jaw and in the rear half of the upper jaw. At this time Marsh finally realized that his 1870 foot-bone had belonged to a Hesperornis.

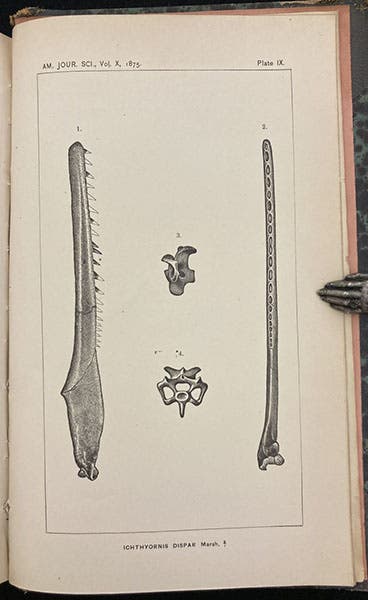

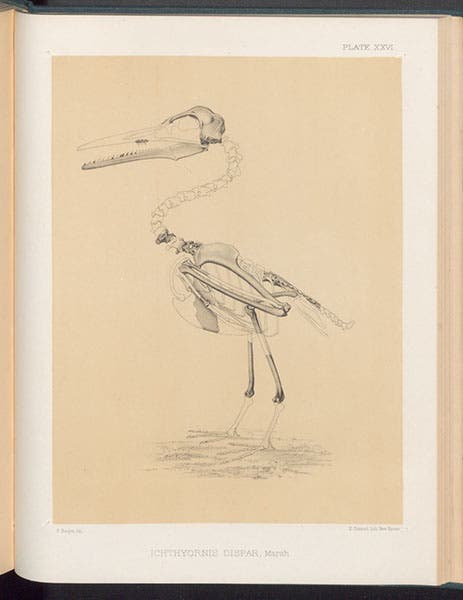

Meanwhile, a Kansas geologist, who would later work for Marsh, Benjamin Franklin Mudge, found in 1871 a much smaller bird-with-teeth fossil from the same formation; he sent it to Marsh, and Marsh named it Ichthyornis dispar. This one could clearly fly, toothy bill and all. It was an even better candidate for a link between birds and dinosaur-like reptiles.

Marsh published at least four short papers on Hesperornis and Ichthyornis in the American Journal of Science, which was published at Yale, giving Marsh a ready outlet for his articles. One of those papers, in 1875, was accompanied by plates illustrating the skulls of the two Cretaceous bird-like specimens, both of which we show here (third and fourth images).

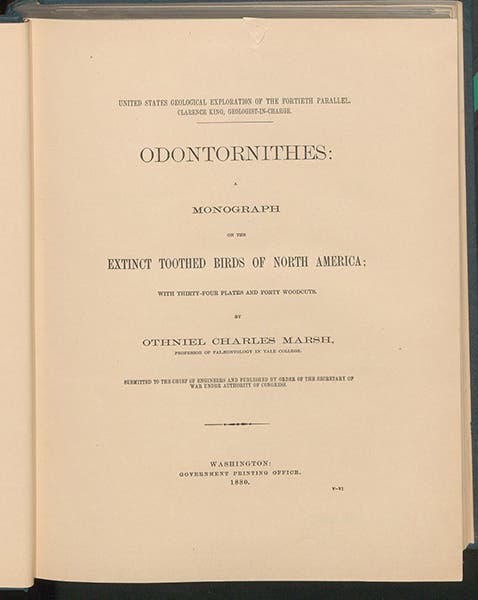

Marsh continued to acquire specimens from his collectors in the Midwest, and he decided to prepare a large monograph on what he called the Odontornithes, the toothed birds. Marsh was friends with Clarence King, who had been leading in the late 1860s and early 1870s an expedition to explore along the 40th parallel. Marsh was not part of the expedition, but when King published the results of his survey in 6 large quarto volumes, he convinced the government to print, as volume 7 (1880), Marsh's Odontornithes. Not only that, he directed that they should print 1000 extra copies of vol 7, which were given to Marsh, who promptly reissued them as vol. 1 of a journal founded on the spot, Memoirs of the Peabody Museum. Since we have a copy of King's Survey Report in our Government Documents, another in our History of Science Collection, and we have the Memoirs of the Peabody Museum, we have three copies of Marsh's Odontornithes. We took our images from the Memoirs volume, since it was in the best condition for scanning (fifth image).

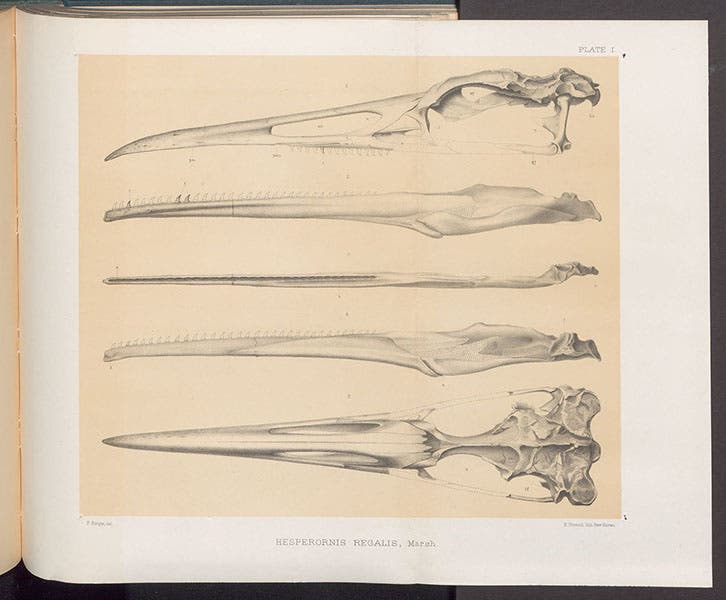

The monograph has 34 large lithograph plates, some of them folding, so it cost the government a pretty penny (and Marsh nothing) to print. We show three of the plates here: plate 1, the pieces of the skull of Hesperornis, with their teeth in place (sixth image); plate 20. a restoration of the skeleton of Hesperornis (first image); and plate 26, a restoration of the smaller Ichthyornis (seventh image). The two restorations appear the same size in the lithographs, but Ichthyornis is twice natural size, while the Hesperornis is half its natural size (about 3 feet tall standing up).

Marsh sent a copy of his book to Darwin, and Darwin replied with a cordial note, sent the day after he received the book, in which he commented: "Your work on these old birds, & on the many fossil animals of N. America has afforded the best support to the theory of evolution, which has appeared within the last 20 years." You can read the letter for yourself on the Darwin Correspondence website.

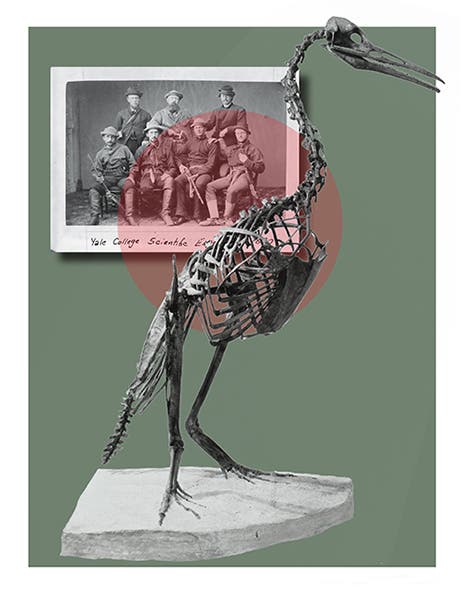

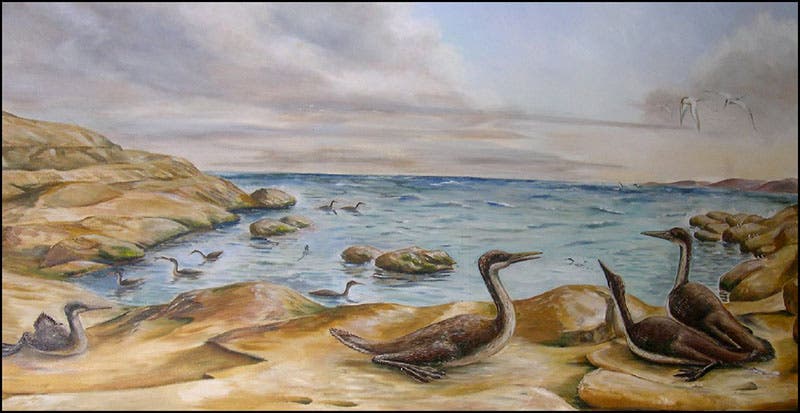

Many fossil specimens of Hersperornis have been found, and they are popular for museum displays, in the form of diving skeletons, standing skeletons. life-like restorations, and paintings and murals. We show here a standing skeleton at the Peabody Museum (eighth image, posed against a 1872 photo of Marsh and his western companions, which we included in larger format in our first post on Marsh). as well as a swimming skeleton in the Canadian Fossil Discovery Centre in Manitoba (ninth image), and a mural on the walls of the Natural History Museum at the University of Kansas in Lawrence (tenth image)

We have at least one more aspect of Marsh’s career to discuss, his discovery of a variety of ancestral horse fossils, including Eohippus, which pleased T.H. Huxley no end. We will not be discussing the "bone wars" between Marsh and Edward C. Cope, which is a too-often-told tale that you can read about in many other fora, including quite a few books. The Wikipedia article “Bone Wars” is as good a place as any to slake your thirst, if such a thirst you have.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.