A Visual History of Eclipses

On Monday, April 8, 2024, a total solar eclipse will cross North America from Mexico to New England with the path of totality passing over 13 U.S. states before entering Canada. To help you get ready for this historic event, Finch Collins, Assistant Curator of Rare Books at the Linda Hall Library, put together this visual history from the Library's History of Science collection.

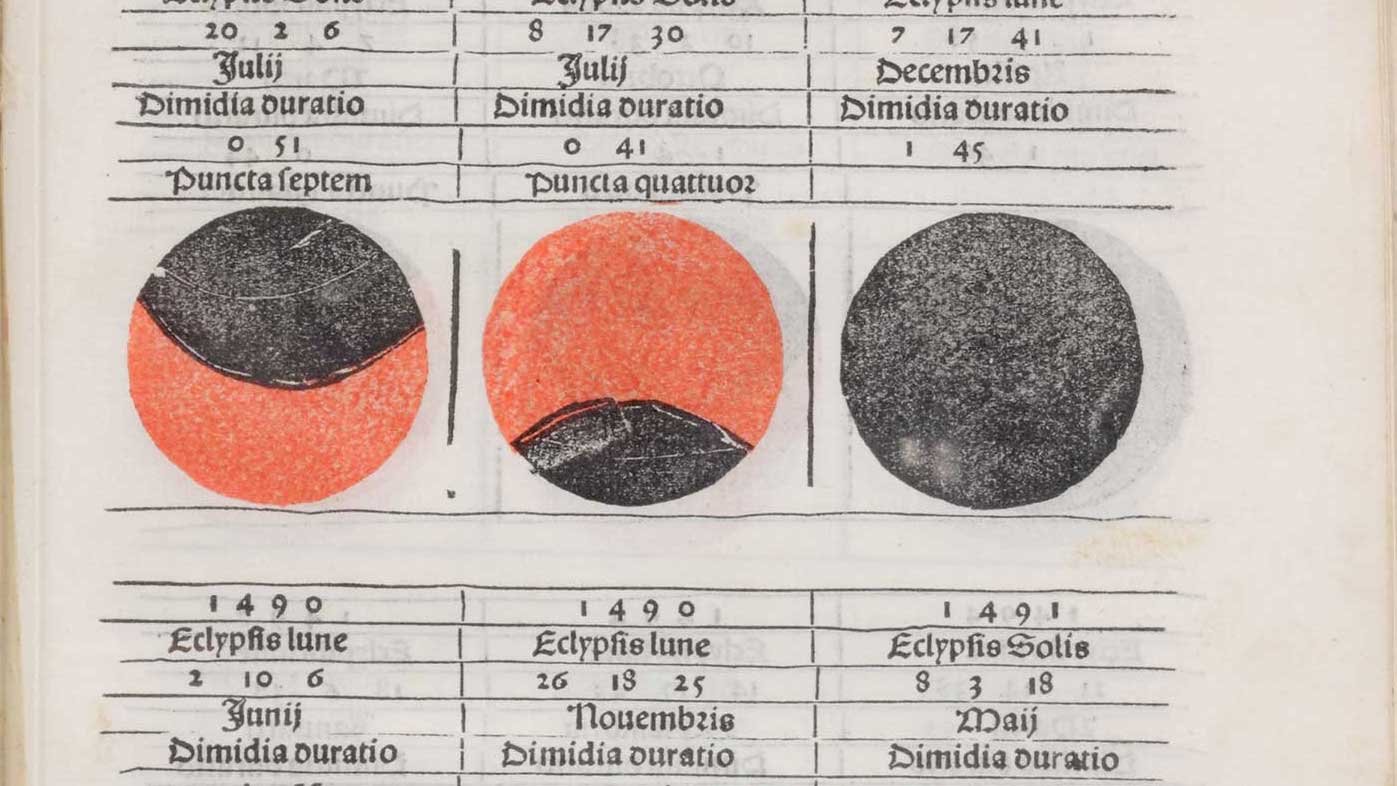

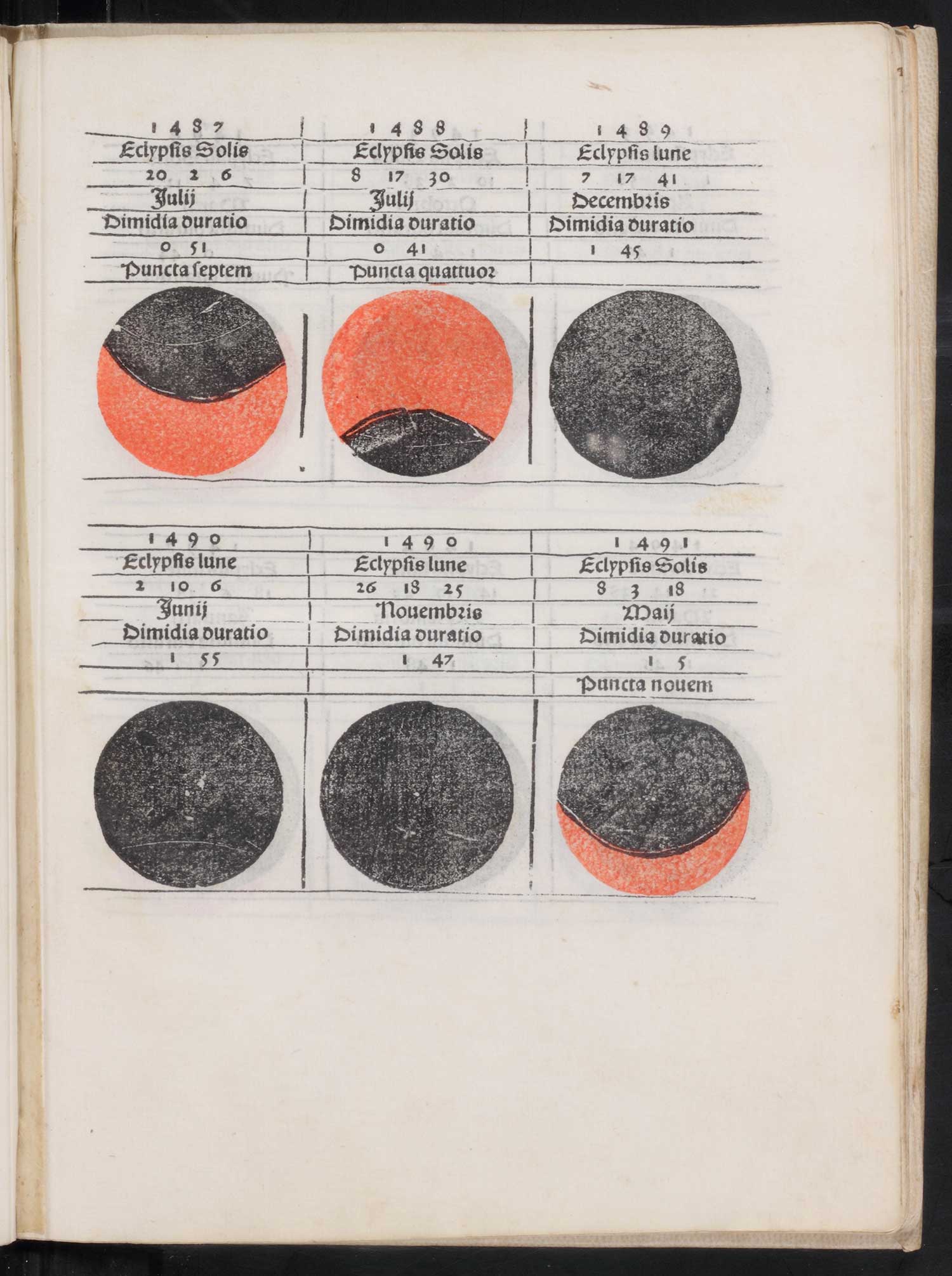

Joannes Regiomontanus, In laudem operis Calendarij. Venice: Erhard Ratdolt, 1485. Leaf B5r.

In the late 1400s, printed calendars contained all sorts of useful information: the dates of Christian holidays, the positions of the sun and the moon on each day, and upcoming solar and lunar eclipses. Regiomontanus’ 1485 In laudem operis Calendarij, or Calendarium, uses two-color printing to illustrate eclipses. This page shows three solar and three lunar eclipses from 1487 to 1491 and predicts their time and duration.

These color images were dramatic innovations in early European printing. At a glance, a reader could understand that the red ink showed the visible portion of the sun and the black ink the obscured portion. More information on Ratdolt’s innovations in color printing can be found in the stellar After Hours with Erhard Ratdolt.

The book concludes with practical tools for the reader to make their own astronomical calculations, including spinning volvelles and a brass pointer that tells the hour for any European longitude. The Linda Hall Library copy has notes and hand-drawn diagrams on the last few pages, suggesting that a past reader used this copy of Calendarium to better understand the movement of celestial bodies and the order of the known universe.

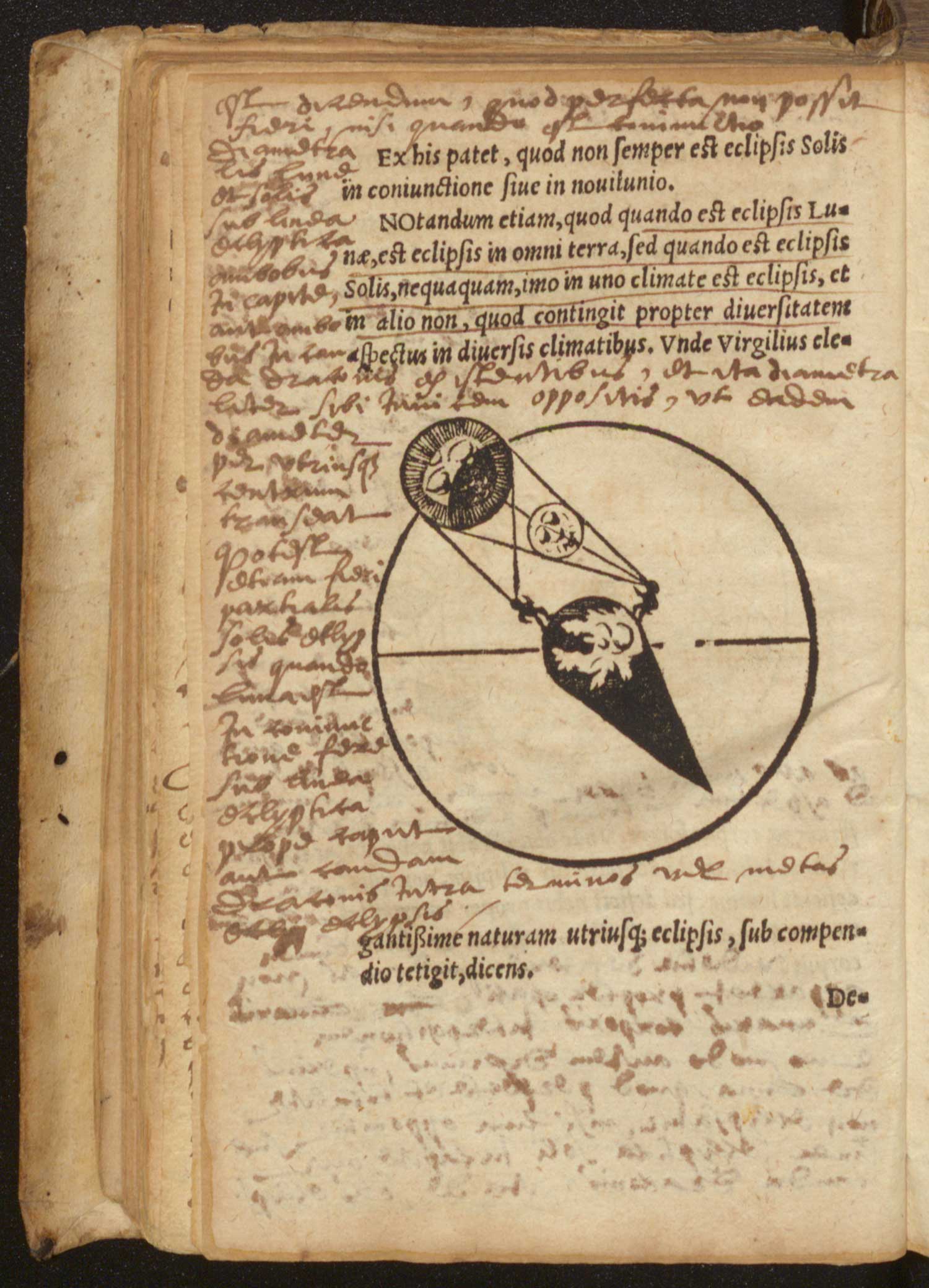

Joannes de Sacro Bosco, Libellus de sphaera. Wittenberg: Ioannem Cratonem, 1553. Leaf G1v.

Sacrobosco’s Sphaera was the single most popular textbook on astronomy in Europe from the 1200s to the early 1600s. One of Linda Hall Library’s copies, published in 1553, is filled with underlines, marginal annotations, and inserted pages of handwritten notes. A past student, perhaps the “Mignoti” whose name is written on the title page, was very engaged with the text!

The section on solar eclipses includes a charming illustration showing solar eclipse totality based on location. In the center, two stick figures stand on the Earth. The Sun orbits the Earth in a ring, and the Moon orbits between the Sun and Earth. From the rightmost figure’s perspective, the eclipse is total, and the Moon casts a complete shadow onto the Sun. From the leftmost figure’s perspective, however, the shadow cast by the Moon is partial. The annotations, though difficult to read for our modern eye, elaborate on the differences between solar and lunar eclipses.

If you’re curious for more on Sphaera and medieval European astronomy, Sacrobosco has been featured in the Library’s Scientist of the Day series.

Giovanni Jacope de Marinoni, Ungula Solis lucida culminans in eclipsi. [Vienna: 1748?].

This single-sheet, anonymous report details the movement of the moon across the sun during a solar eclipse seen from Vienna, Austria on July 25, 1748. The report describes the “bright hooves” of the sun that are formed as the moon moves in front of the sun during a solar eclipse. At top, two images show the shadow of the moon and the hoof-shaped sliver of sunlight that remains. Linda Hall Library is the only library in the United States that has a known copy of this report.

The report is part of a seventy-four letters, reports, and pamphlets gathered by the French astronomer Jean François Séguir. Sixty-nine of those items, including this one, are bound together into a book. Séguir was a naturalist and astronomer who corresponded with astronomers across Europe, sending and receiving handwritten and printed observations, reports, pamphlets. Séguir wrote notes on and around the items he received. We can attribute this report to Giovanni Jacope de Marinoni, an Austrian mathematician and astronomer, because Séguir wrote a table of contents at the front of the volume.

De la Rue, Warren, “The Bakerian Lecture: On the Total Solar Eclipse of July 18th, 1860, Observed at Rivabellosa, Near Miranda de Ebro, in Spain,” in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 152 (1862).

Photography was transformative in solar eclipse observation. In the 1850s, Warren De la Rue devised the photoheliograph, a special-purpose telescope which enabled him to take a daily photograph of the solar surface. In 1860, he and his team carried the photoheliograph to Spain to photograph the July 18th total solar eclipse. De la Rue’s photographs, presented in the 1862 issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, proved that coronal mass ejections were not artifacts of telescopes, human eyesight, or the photographic process, but physical emanations from the sun. Plate 7 reproduces De la Rue’s photograph of coronal mass ejections at the start of totality in beautiful chromolithography. The Moon’s De La Rue crater is named after him.

A Lady Astronomer [Elizabeth Brown], In Pursuit of a Shadow. Cirencester: Baily & Woods, [1890s].

In Pursuit of a Shadow narrates two eclipse-chasing journeys by Elizabeth Brown, a female solar astronomer working in the late 1800s. As a woman, Brown was excluded from the highest formal scientific circles. Her 1887 and 1889 eclipse travels were likely self-funded, as she was not part of the official Royal Astronomical Society observation team. The Royal Astronomical Society did not accept women as fellows until 1916.

Brown published In Pursuit of a Shadow anonymously and anonymized the identity of her companion. Recent research by Joel Beckles and Deborah A. Kent has identified this companion as Brown’s second cousin, Miss Martha Louis(a/e) Jefferys, born 1859. Brown and Jeffrys traveled to Russia and the West Indies to observe the solar eclipses. In Brown’s account of the 1887 eclipse in Russia, she describes how a cloudy sky frustrated the observers, both formal members of the eclipse team and those making their own way.

The Linda Hall Library copy of In Pursuit of a Shadow is inscribed in the front, gifting it to a “Millicent, from Aunties Juno & Louie” on February 24, 1898.

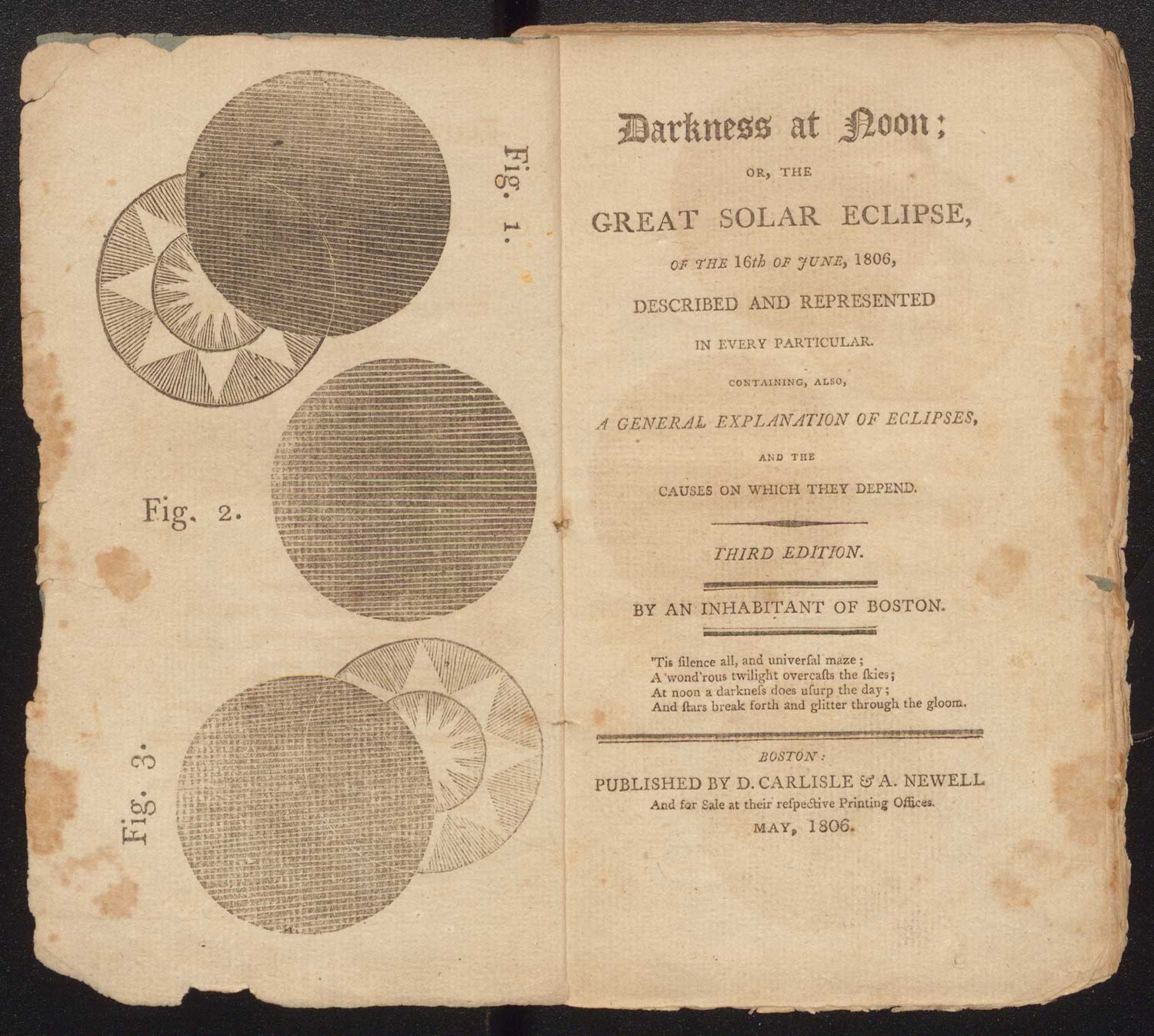

Newell, Andrew, Darkness at Noon: or, the Great Solar Eclipse of the 16th of June, 1806. Boston: D. Carlisle & A. Newell, 1806.

In 1806, a solar eclipse passed over the northeast of the young United States, with the path of totality including the bustling city of Boston. Andrew Newell, a printer and instrument maker, authored and published this anonymous pamphlet to educate Bostonians on the coming “darkness at noon.” The pamphlet is small and fragile, which makes its survival to the present even more extraordinary. The Linda Hall Library copy is still covered in blue paper and bound together with a single string, as it left the bookstore in May of 1806.

While Newell’s explanation remains accessible, if written in archaic language, his instructions for viewing the eclipse should be left in 1806. Newell advises the reader to view the eclipse through “a piece of common window glass, smoaked on both sides sufficiently to prevent any injury to the eye.” If you’re viewing the eclipse next week, do not take this leaf out of Newell’s book!

![Giovanni Jacope de Marinoni, Ungula Solis lucida culminans in eclipsi. [Vienna: 1748?].](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/ea434b70-56bb-45fb-a83e-72b929d9b6bb/3-Eclipse_de%20Marinoni.jpg?w=1500&h=1426&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![A Lady Astronomer [Elizabeth Brown], In Pursuit of a Shadow. Cirencester: Baily & Woods, [1890s].](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/faff57d2-7e1f-4831-ad47-f41b7db8e4ac/5-Eclipse_Elizabeth-Brown.jpg?w=1500&h=1071&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)