New Acquisition: A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, 1955

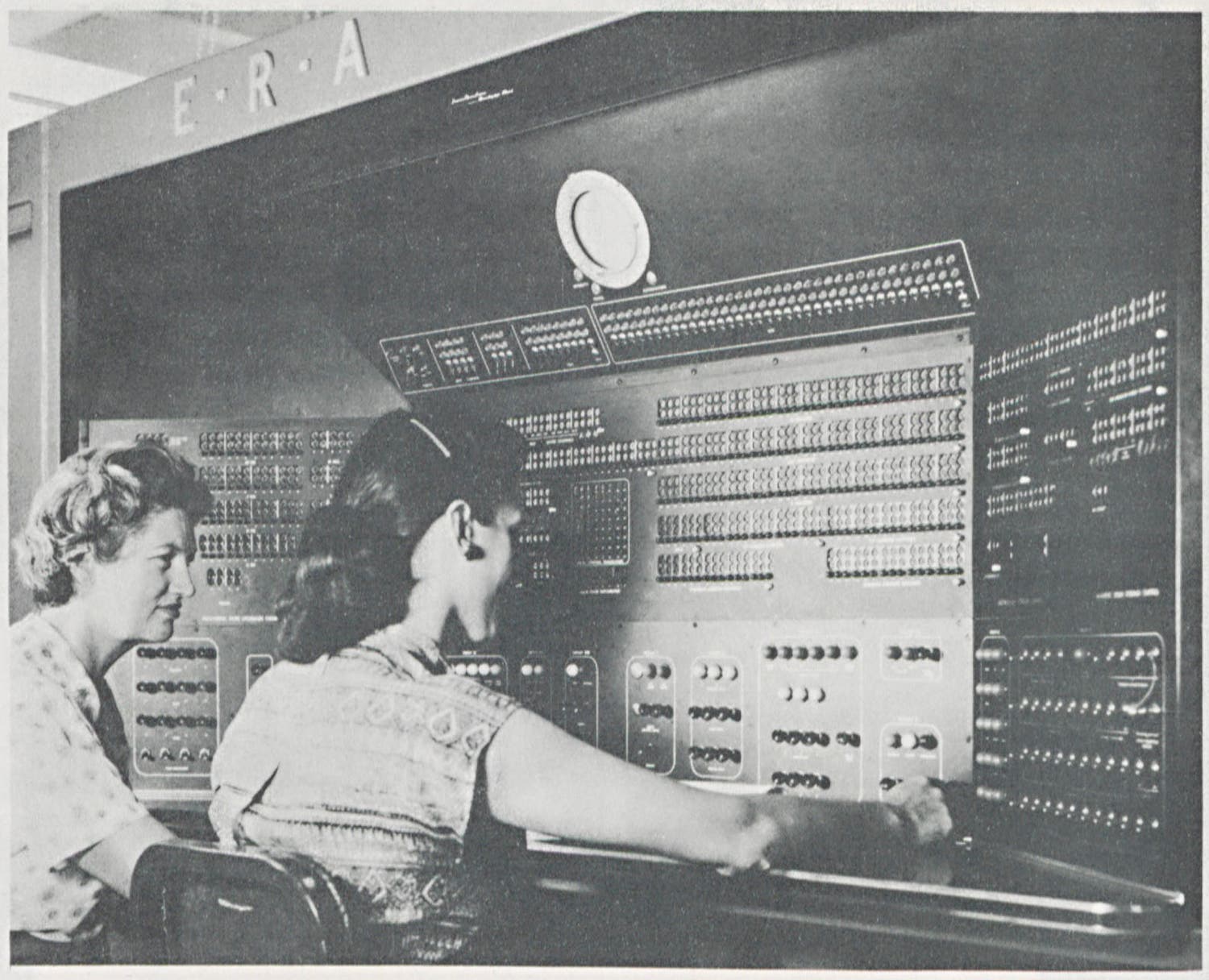

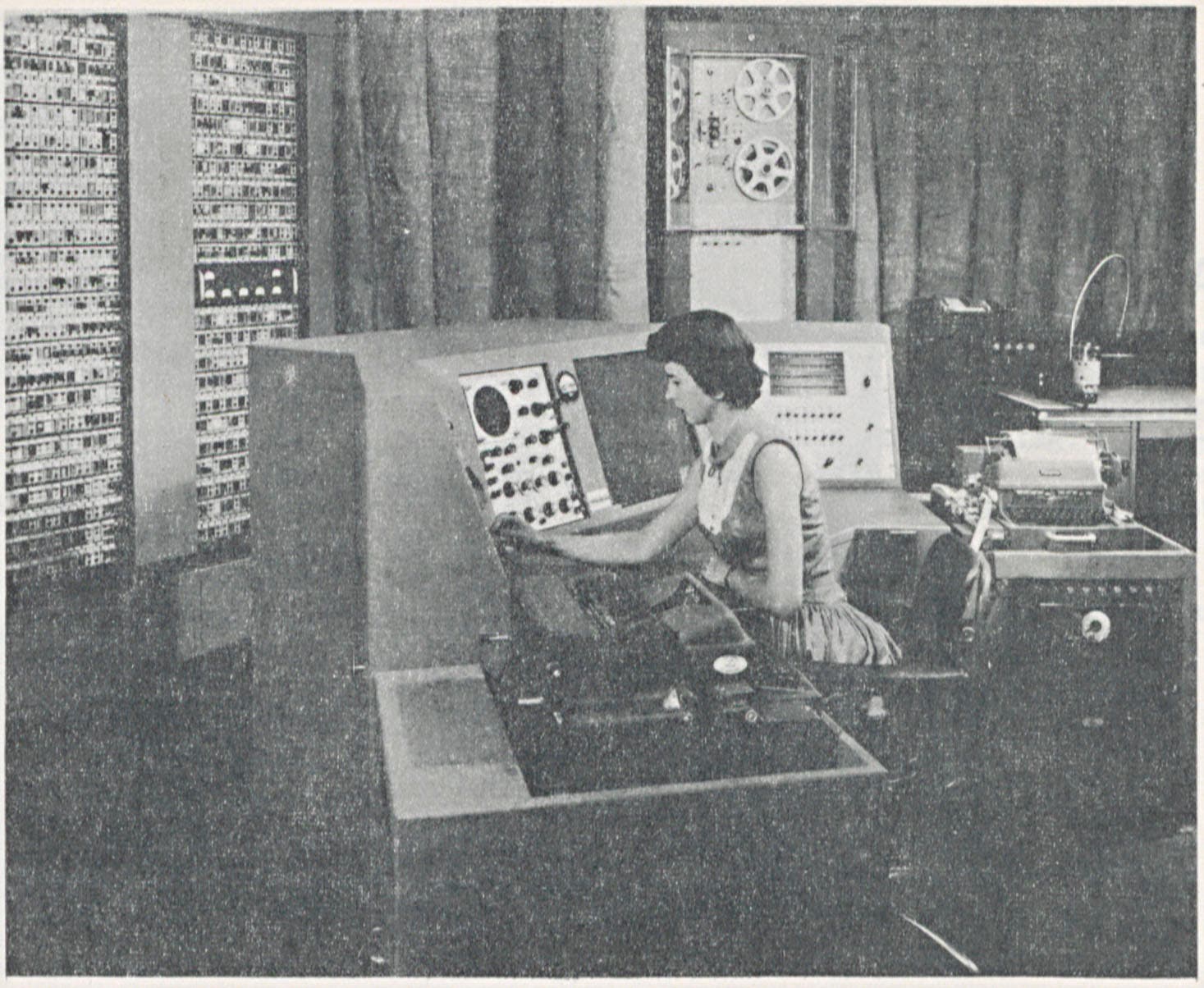

Two women program and operate a UNIVAC-SCI computer, in A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, by Martin H. Weik, 1955, p. 189.

In 1955, digital electronic computers were new technology. Things we take for granted today, like stored programs and direct keyboard input, had to be invented and incorporated into new models. Early computers evolved almost as quickly as they were built. Before 1945, mechanical or electromechanical computers used physical switches in binary positions to perform computer operations. The first programmable electronic computer, the ENIAC, was completed in 1945 and could make calculations one thousand times faster than electro-mechanical machines.

Ten years after the ENIAC’s completion, where was the field of computing? One document, acquired by the Library in April 2024 from the Washington D.C.-area rare book firm Type Punch Matrix, presents information on that rapid evolution as it was happening.

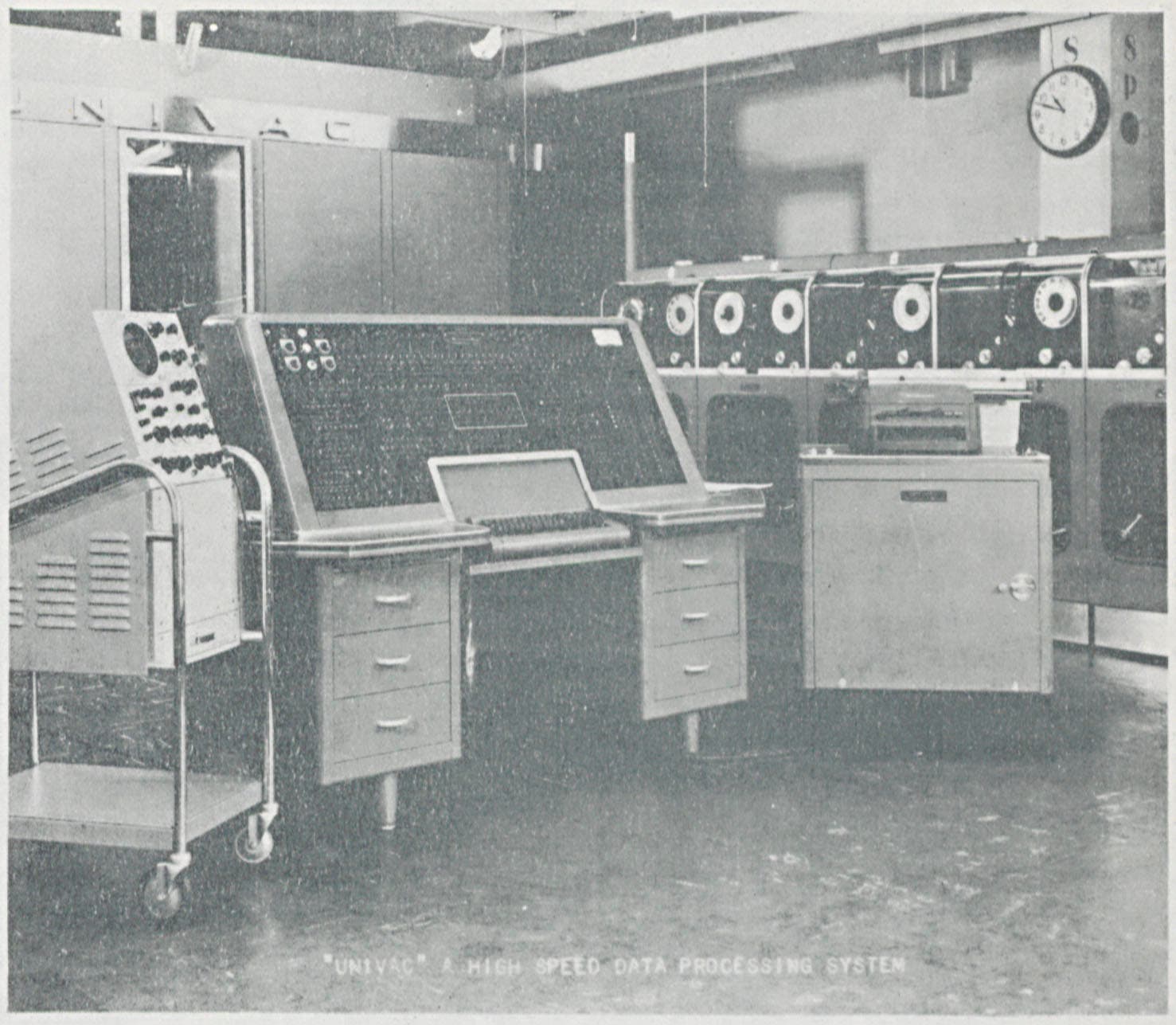

The UNIVAC, or Universal Automatic Computer, in A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, by Martin H. Weik, 1955, p. 177.

A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, published by the U.S. Government in 1955, details eighty-eight computers then in operation in the United States. The survey was overseen by Martin H. Weik, the director of the Ballistic Research Laboratories (BRL) at the U.S. Army Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland; his name appears on the title page. In a 1996 interview, Weik described their motivation for the survey:

“[W]e wanted to get data on a lot of machines that were available, either about to be built, being built, or being applied. There was little information about experience on computers and applications on computers, so we thought it would be a good idea to find out all about all the computers that existed in the world at that time. So, we came out with the idea to survey all the computers.”

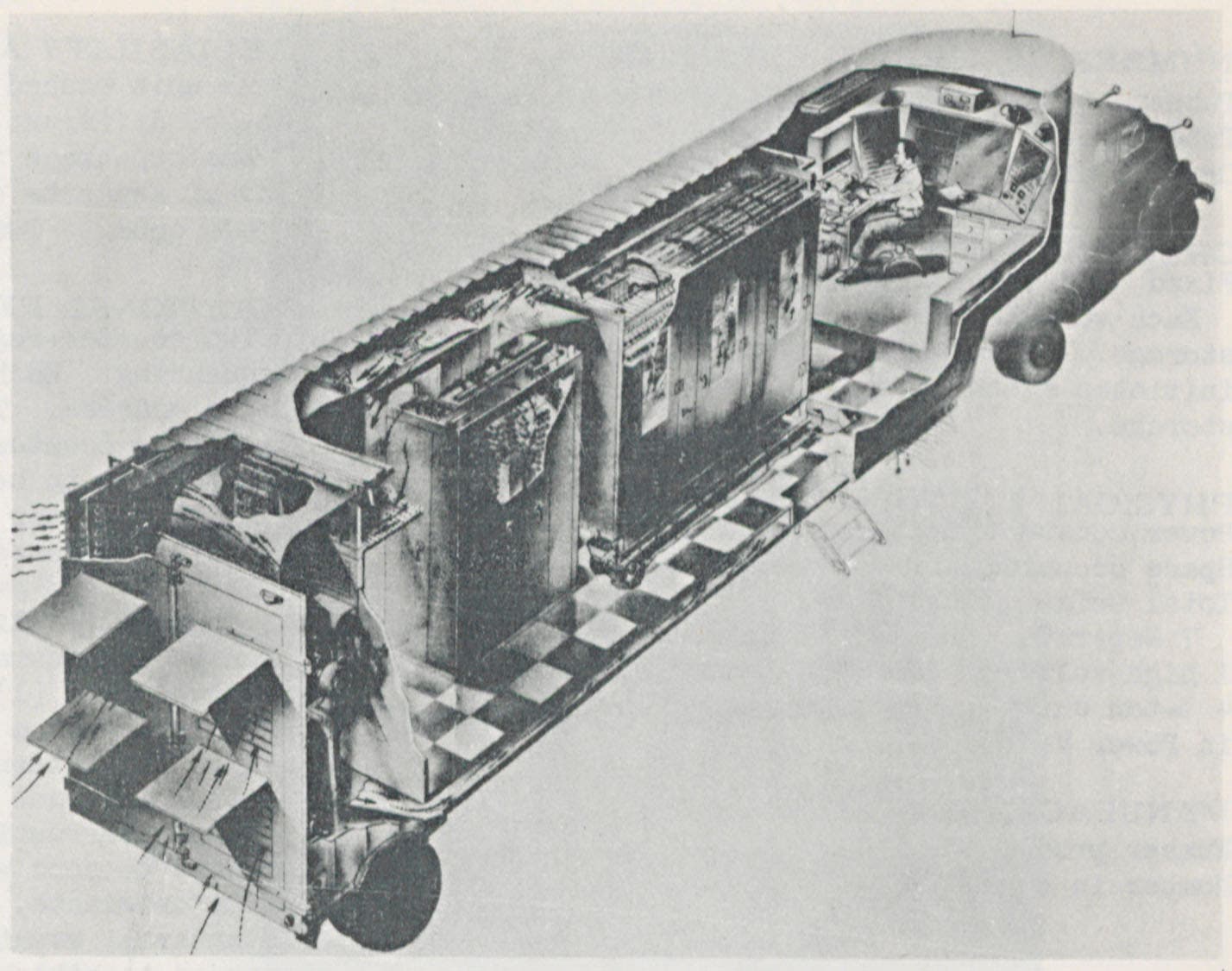

The DYSEAC, or Second (DY) Standards Electronic Automatic Computer, shown housed in a semi-trailer. In A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, by Martin H. Weik, 1955, p. 25.

The report describes the input, output, arithmetic, control, and storage units of the computing systems, as well as information about the manufacturer, personnel requirements, and cost. These were massive and expensive systems, and many existed in only one copy. This portable DYSEAC is portable because it’s built inside a semi-trailer!

![Stamp of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Library stating the report was “cancelled [sic] as surplus to requirements.” From the LHL copy of A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, by Martin H. Weik, 1955, front wrapper and title page](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/863d181b-0bfc-42d8-b8bc-57d89eea6962/06.2024%20New%20Acq%20Survey%204-3543_0001.jpg?w=1195&h=712&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Stamp of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Library stating the report was “cancelled [sic] as surplus to requirements,” and ownership stamp of the H.M. Nautical Almanac Office, struck through. From the LHL copy of A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, by Martin H. Weik, 1955, front wrapper and title page.

Our copy of the report has stamps from the Royal Greenwich Observatory (RGO) Library at Herstmonceaux Castle in Sussex, UK, which has a complicated history of its own. The Royal Observatory was commissioned in the 17th century by the British crown (for a story of an 18th century astronomical rivalry that takes place at Greenwich, I recommend After Hours with Historia Coelestis). By the 20th century, atmospheric pollution in Greenwich, outside London, impeded astronomical observations. The observatory merged with the H.M. Nautical Almanac Office (HMNAO) and moved to the rural Herstmonceaux Castle in the 1930s. The RGO closed in 1998, one year after this report was deemed “surplus to requirements.” It’s possible that the HMNAO, which produces astronomical data, were considering investing in a computing system for their calculating needs.

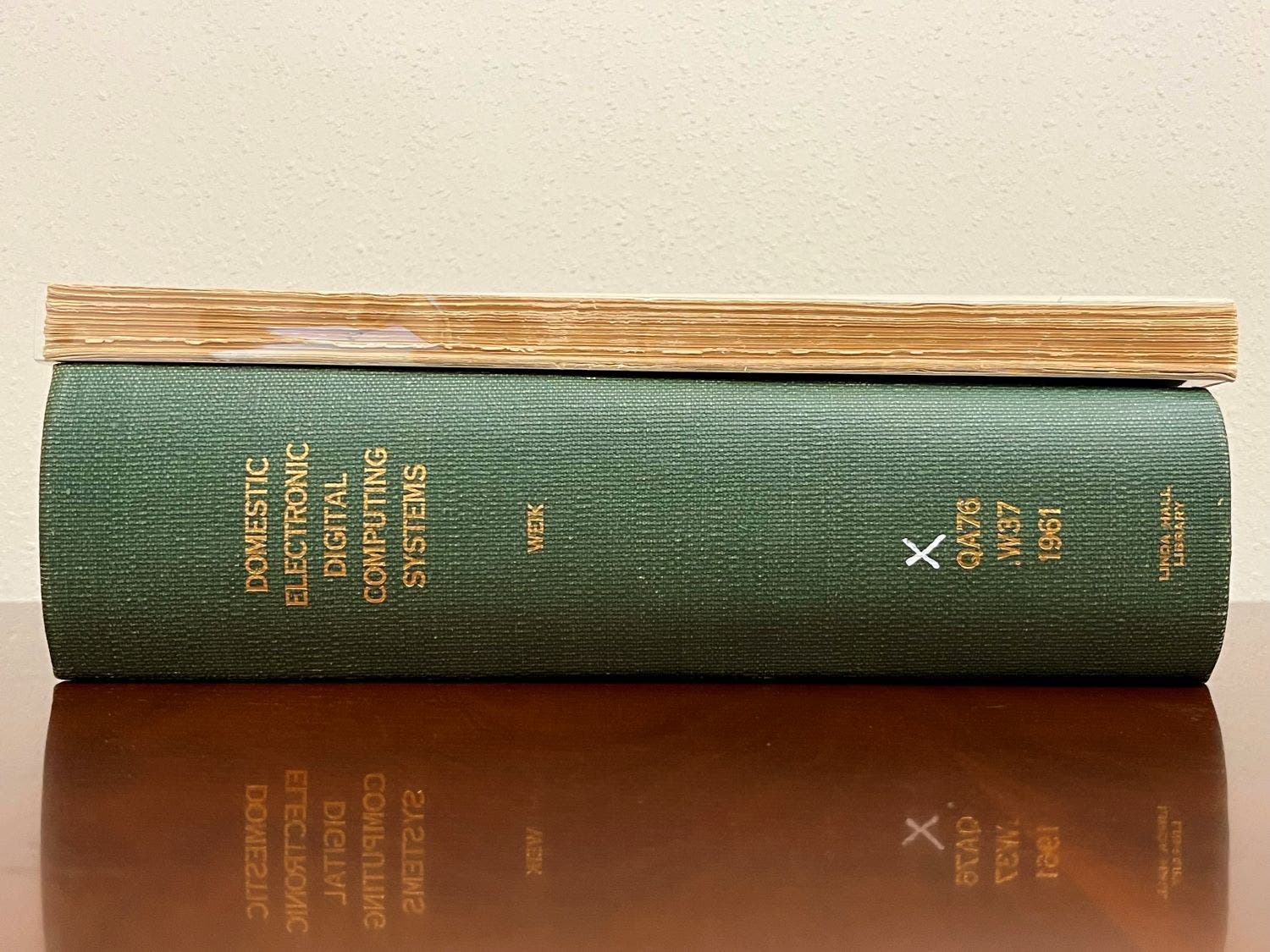

The 1955 survey atop the 1961 survey, with a green binding.

The Library already had a copy of the 1961 A Third Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, which we purchased directly from the U.S. Office of Technical Services at the time of publication. The third survey describes 222 different electronic digital computer systems—a nearly threefold increase from six years earlier. The respective sizes of the books speak for themselves!

A woman programs and operates the FLAC, or Florida Automatic Computer, in A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems, by Martin H. Weik, 1955, p. 48.

A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems strengthens our holdings in pre-1960 computer history. Whether you’re a computer buff, a historian, or a modern computer scientist, this survey has something to offer. Technical details illuminate the inner workings of long-defunct computers, while information on cost and personnel place early computers in their social, economic, and political context. The photographs add a human element: unnamed women and men program and operate the room-sized machines. Who are they? As Bill Ashworth notes in his Scientist of the Day post on Jean Jennings Bartik, captions to photographs of women with computers often describe them as “operators” even if they were responsible for all the programming. Some answers may be found in the second survey—if you have a copy on your bookshelves, do please let us know.

For more on early computing at the Ballistic Research Laboratory, including a detailed interview about this survey (quoted above), consult Martin H. Weik, “1939-1954: ENIAC and the First Computer Survey,” in 50 Years of Army Computing: From ENIAC to MSRC (2000), which can be accessed via the Defense Technical Information Center online catalog.