Scientist of the Day - Abraham Darby III

Abraham Darby III, an English iron manufacturer, was born Apr. 24, 1750. Darby came from a long line of ironmasters who worked in Coalbrookdale in Shropshire. His grandfather, Abraham I, had invented the coke-fired blast furnace in 1709 (previous blast furnaces used charcoal as fuel, but England was running out of wood for charcoal, whereas coal for coke was plentiful, especially in Coalbrookdale). In 1774, Abraham III got involved in a project to build an iron bridge over the River Severn in Shropshire.

In 1773, Thomas Pritchard, an architect of Shrewsbury, 17 miles upriver, made a proposal to build an iron bridge to connect the industrial town of Broseley, on the south bank of the Severn, to Madeley, on the north bank, and to Coalbrookdale. Important civic members of the area met in 1774 and agreed to submit a proposal to Parliament for an Act of Authorization. Abraham Darby III was one of those civic fathers. Parliament approved the plan in 1776, and Darby won the contract to supply the iron. But Pritchard died in 1777, and Darby had to carry on alone, turning Pritchard's preliminary design into reality.

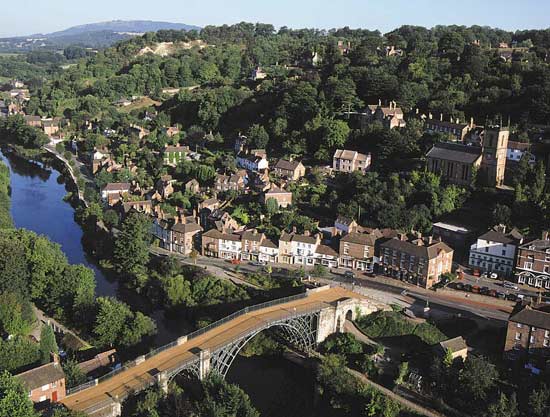

Aerial view of Iron Bridge and the surrounding area (coachbookings.com)

The bridge was to rest on 5 parallel arches trussed together, with a span of 100 feet. The arches were cast in two parts, each half about 70 feet long, and bolted together at the middle (which is to say, the top). Darby's family furnaces were in Coalbrookdale, some miles away, but he had bought two furnaces at Bedlam, not 1500 feet from the site of the bridge, and so most of the casting was done there. The spans and their supports required nearly 500 separate castings (not counting the 1000 cast pieces that were used for the road bed and railings. The elements of the spans were sand-cast, and rather than being made from a standard mold, they were cast to fit, which means every casting was a little bit different. Many of the bridge pieces have the date “1779” cast right in.

The bridge was finished in 1779 but was not open for traffic until Jan. 1, 1781; the delay in opening was caused by the lack of any approach roads, which had to be built before the bridge could be used. Iron Bridge still stands, which is rather amazing. No doubt one of the reasons for its longevity is that the bridge was drastically overbuilt, with many more iron supports than were really necessary for a bridge of this size. Many of the supports have now cracked, but enough intact ones remain that it can still be used, although now it is restricted to pedestrians only. One of the bridge's more interesting features are the joints in the struts that support and connect the large arches. Pritchard, a woodworker, didn't really know how to fasten iron castings together, so in many places he called for woodworking joints, such as dovetails and mortise-and-tenon to join his ironwork. Darby managed to make the dovetails work.

There is a museum in Ironbridge (the town is one word, the bridge two), called the Ironbridge Gorge Museum, which has a diorama reproducing the bridge and the gorge in miniature (but not too miniature – the diorama is 40 feet long). So if you go to Ironbridge the town, you can see a model of Iron Bridge to scale, and then you can go outside and see it full size. A double treat.

It is hard to overestimate the importance of Iron Bridge. It was constructed at the very beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England, at the very geographical center of that revolution. As one historian put it, Iron Bridge was so significant, not because it showed how an iron bridge should be built, but because it showed that an iron bridge could be built. In its aftermath, people started using iron for everything--door lintels, window frames, axle trees, mile posts, grave stones--and the Industrial Revolution, aka the Iron Revolution, was off and running. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.