Scientist of the Day - Abraham Lincoln

On May 22, 1849, the U.S. Patent Office awarded a patent for a device to help boats trapped in shallow water escape their predicaments. Ordinarily, we never commemorate patent-grant dates in this space, because we have always considered such dates to be false anniversaries, mere happenstances of bureaucratic calendars. We violate our rule today because the patent applicant in this instance was Abraham Lincoln, the only U.S. president to ever apply for and receive a patent for anything, and because the patent model is very cool. We never get to do Lincoln’s birthday, since he shares it with Charles Darwin, so his patent-day provides the perfect occasion for a small celebration.

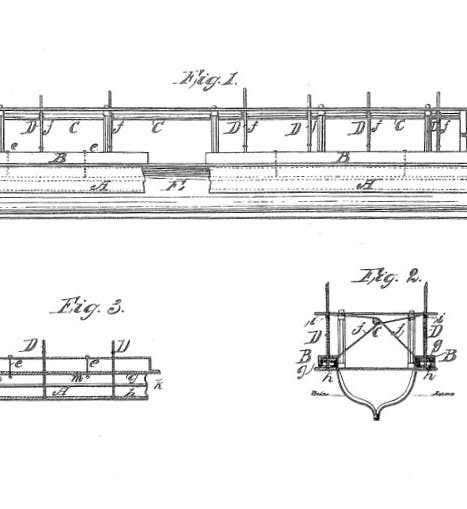

In 1849, Lincoln was 40 years old and had just returned to Springfield from his first two-year term in Congress. According to his law partner, Lincoln as a younger man had taken several river voyages, during which his boat was hung up on rocks or shoals and could only be extricated by unloading the cargo and floating the boat, a great inconvenience. Lincoln had the idea of attaching sets of inflatable bellows along each side of the boat, so that when the ship got stuck, the bellows could be inflated by a drive mechanism and decrease the displacement, and then the boat would float free. You can understand the mechanism a little bit better (but not a lot) from the drawing that accompanied the patent application (first image). Although our Library is a patent repository, we do not have the paper patent for Lincoln’s invention in our collection, but you can see it, as you can see any patent, on Google Patent.

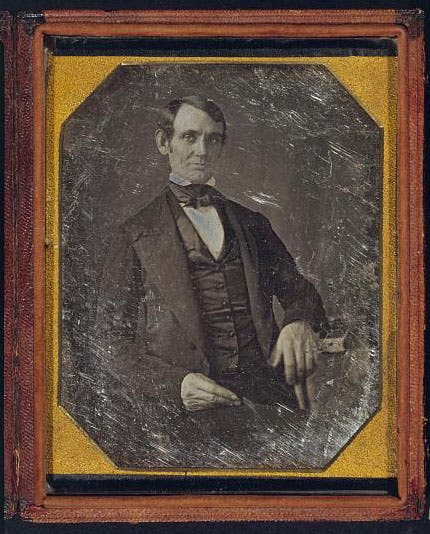

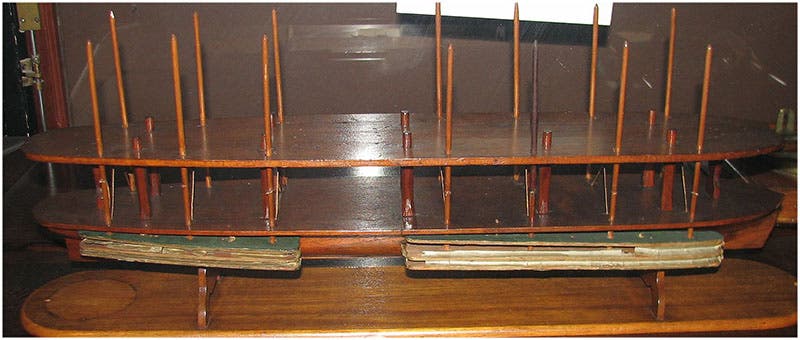

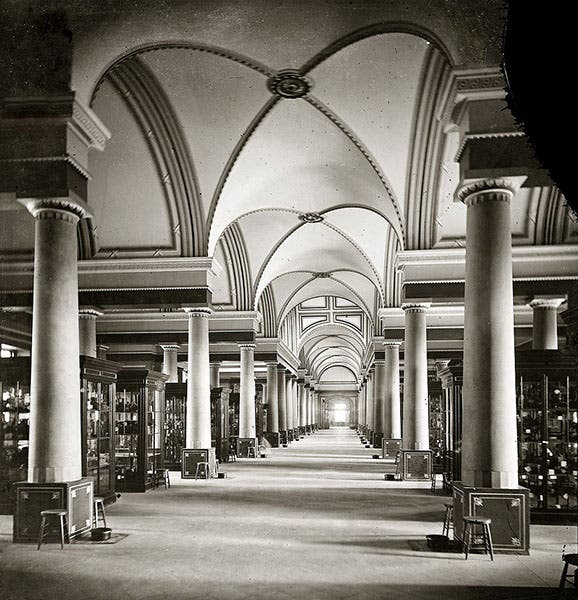

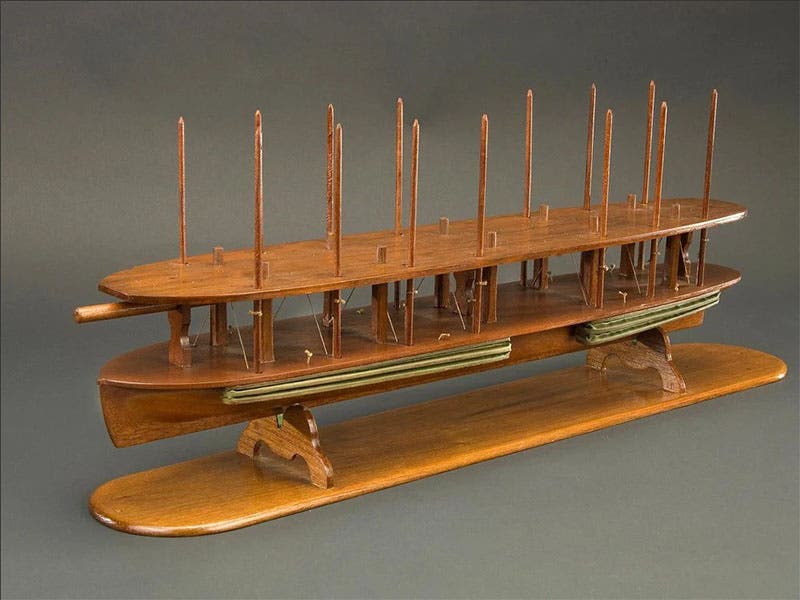

When Lincoln submitted his application in March of 1849, he accompanied it with a wooden model that still survives. It sat in the U.S. Patent Office Model Room until 1922 (fifth image), when it was transferred to the National Museum of American History, part of the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C. Photographs allow one to make out the bellows that run along the side of the keel and the vertical poles that are connected to a long horizontal shaft (now missing) that runs lengthwise down the middle of the boat. When the shaft is rotated by the engine, the poles push down, the bellows expand and inflate with air, and the boat is raised higher in the water.

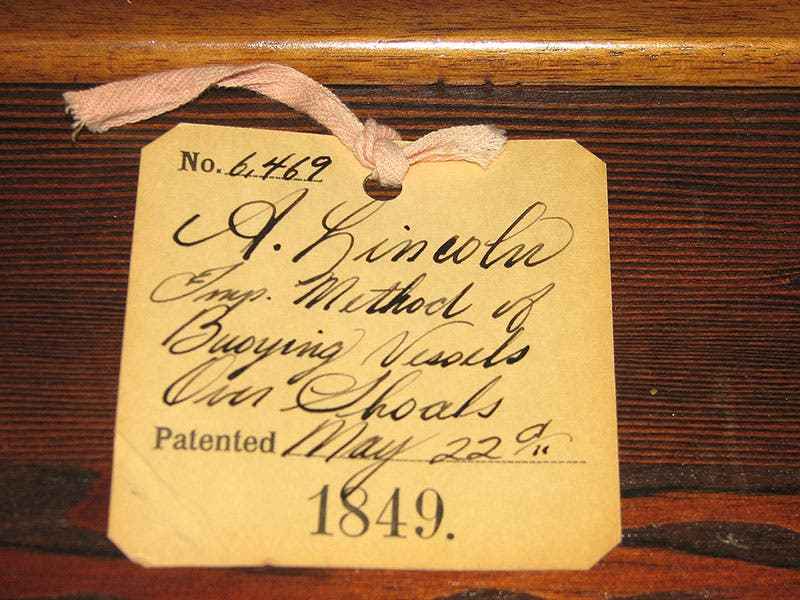

The original model is no longer on display, being rather fragile, and has been replaced with a too-fresh looking replica (sixth image). The original model still has the original paper ID tag attached, with the number of the patent (6,469), today’s date (but in 1849), the title of the application: “Improved Method of Buoying Vessels over Shoals,” and, of course, the second-hand signature, “A. Lincoln” (fourth image).

We don’t know who made the model – probably not Lincoln, since his first name is misspelled (Abram) on the signed model. And the patent was apparently never implemented. When asked their opinion, most modern experts allow that the device would never work – that it would take much more force than would be available to turn the shaft and inflate the four sets of bellows. But mostly, no one asks, or cares. It is quite enough that Abraham Lincoln, a patent attorney after all, exercised his mind in a clever and interesting way, and had a model built, before taking the tribulations of a land divided onto his formidable shoulders.

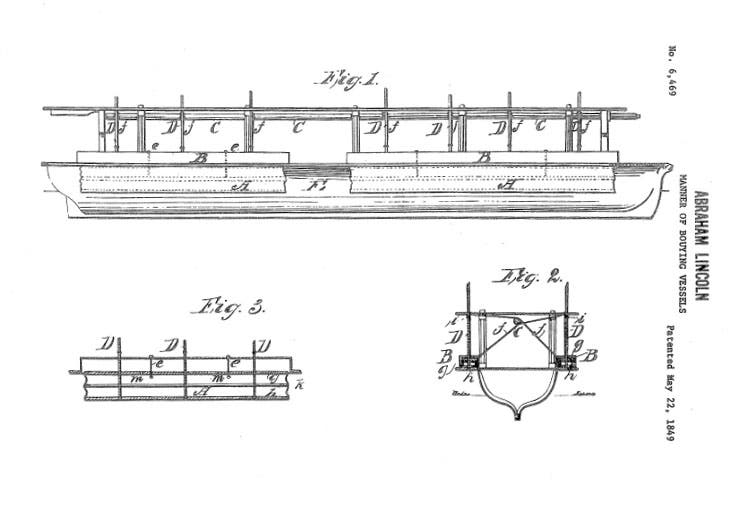

The portrait (second image), a daguerreotype, is the oldest known photo of Lincoln, and was taken in 1847, when he was 38, just two years before he submitted his patent application. It is preserved in the Library of Congress.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.