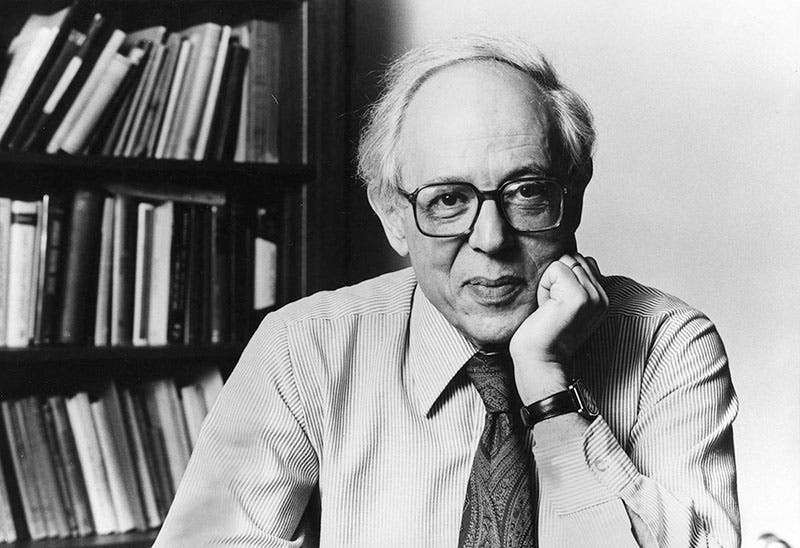

Scientist of the Day - Abraham Pais

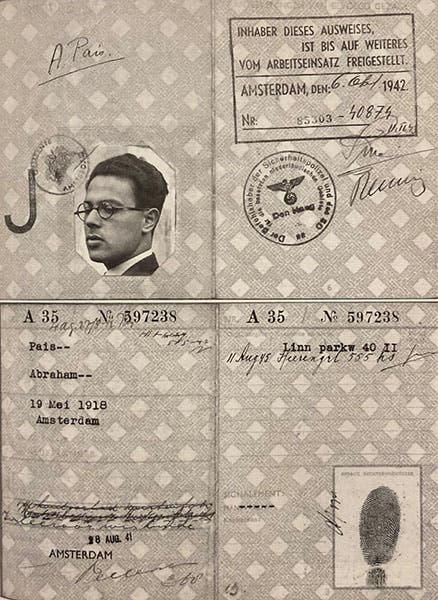

Abraham Pais, a Dutch-American Jewish theoretical physicist and would-be historian of science, was born May 19, 1918. He studied physics in the Netherlands, his final years of study at Utrecht made more difficult by the German invasion of Holland and Belgium. The occupying Germans issued a decree that Jews would be excluded from Dutch higher education, and Pais had to work frantically to pass the requirements for his PhD before that ban took effect. He was in fact the last Jew to get a PhD in the Netherlands until 1946. His wartime experience was harrowing, as detailed in his autobiography, A Tale of Two Continents: A Physicist’s Life in a Turbulent World (1997), which I had owned for many years but had never read until preparing this essay. Since he was a physicist, and therefore of potential value to the Germans, he was issued a card that exempted him from being deported to a concentration camp in Germany (second image), but for 5 years he had to wear a star of David in public that identified him as a Jew, and as the crackdown on Jews grew more intense in 1943 (hundreds of thousands of Dutch Jews were sent to German camps, and most of them did not survive), Pais ultimately had to go into hiding.

The wartime ID card of Abraham Pais, exempting him from exportation to a concentration camp, reproduced in A Tale of Two Continents, by Abraham Pais (Princeton Univ. Press, 1997; author’s copy)

Pais was aided in his extended concealment from authorities by his former fiancée, Tina Strobos, who went by the name Tineke Buchter at the time. She is the young woman in the first photograph. Barely 20 years old at the start of the war, Tineke and her mother (the other woman in the photo) went into the business of hiding Jews in their house in Amsterdam, building a hidden compartment in the attic of their home and procuring forged documents to help refugees flee the country. The two women provided secret shelter for some 100 Jews over the course of 4 years and helped smuggle many more to hiding places out in the countryside. Her house was raided 9 times by the Gestapo, nearly always when someone was in hiding upstairs, and the police never found anyone, as they had an elaborate system of warning buzzers to alert refugees when the police were at the door, as well as an escape route along the roof. Tinkeke found a place for Pais and three friends to hide out in 1944 when his position had become untenable, and when Pais’s hiding place was betrayed by another ex-girlfriend and he spent a month in prison, Tineke was the one who secured his release, waving a letter from Niels Bohr praising Pais's scientific abilities in front of a Gestapo officer. Had the Allies by this time (April 1944) not cut off the German railroad lines from North Holland to Germany, Pais wojuld have been shipped to the camps before he was released. His male companion in hiding, who had assisted at Pais's PhD ceremony, was executed even while Pais was being released. Pais never explains why he and Tineke decided in 1943 to break off their engagement. She was, it seems, a truly remarkable woman.

I am sure such a wartime experience colors a man's life, but Pais seemed to rise above it. After the war, he studied with Bohr in Copenhagen, and then at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, where the most distinguished resident was Albert Einstein, with Wolfgang Pauli also in residence. When Robert Oppenheimer took over as director of the Institute in 1947, Pais was the first person he sought out to sign to a long-term contract. Pais spent many hours discussing physics with Oppenheimer (and Paul Dirac) in the Commons room at the Institute, and with Einstein in his office.

It was interesting to read in Pais’s autobiography how revered Einstein was by other members of the Institute. When Einstein would drop in on a seminar, which did not happen often, but did to Pais, everyone froze, and mouths went dry, as speakers tried to pick up their train of thought. Pais was one of those (with Kurt Gödel) who used to walk Einstein home at lunch to his house not far from the Institute. He would later write a biography of Einstein.

Pais's work is hard to explain, and I won't try, except to say that he was a theorist, not an experimentalist, and he was concerned with new intermediate particles called mesons, which were soon discovered to be of several kinds, pi-mesons (or pions), mu-mesons (or muons), and k-mesons (kaons). Pais was one of those invited to the Shelter Island Conference in 1947, the first post-war gathering of the world’s leading theoretical physicists, where the main topic of discussion was quantum electrodynamics (QED), which attempted to explain and predict all nuclear reactions, especially those involving mesons. There, Pais was able to spend time with Richard Feynman, who had just developed his “Feynman diagrams” to predict the outcome of nuclear interactions. In a photograph taken at the conference (third image), Pais sits on the sofa, just to the left of Feynman, who is scribbling madly on a sheet of paper, while Oppenheimer, pipe in mouth, looks on from the arm of the couch at left

With an American physicist, Murray Gell-Mann, Pais later discovered a new quantum property called “strangeness” (an addition to charge, angular momentum, and spin) which distinguishes the three kinds of kaons.

After leaving the Institute in 1963, Pais spent the rest of his career at Rockefeller University, where he eventually turned from physics to the history of physics. He published a history of 20th-century physics in 1988, a biography of Niels Bohr in 1991, and in 1994, he published his acclaimed biography of Einstein: Subtle is the Lord ...': The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. He also wrote a biography of Oppenheimer which was uncompleted when Pais died in 2000, but has since been published. I should confess up front that I, a professional historian of science, am not favorably disposed toward scientists who think that history is what you do when you retire from real work and are looking for a hobby to occupy your dotage. I didn’t mind George Gamow writing histories of physics, because he acknowledged that he was a mere anecdotalist and never pretended to be a historian, and besides, he was irreverently delightful. But Pais took his new historical calling seriously. I found Subtle is the Lord almost impossible to read (and I have a degree in physics) – it was just too technical, and I never finished it. Pais’s autobiography was informative, but it appears to have been written by jotting down notes on a few thousand index cards and then stringing them together in some kind of sequence, with no further continuity in evidence. I learned a great deal about his life, but the book had no literary style and lacked any kind of structure except the chronological one. I do not think I will be reading the rest of Pais’s opera, although I am sure I will be looking things up in his various volumes. He was, after all, right there when it all happened.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.