Scientist of the Day - Adriaan van Maanen

Adriaan van Maanen, a Dutch astronomer, was born Mar. 31, 1884. In the 1910s, having moved to the United States to work for the Mount Wilson Observatory in Pasadena, van Maanen began measuring the rotation speeds of spiral nebulae. Spiral nebulae were wispy astronomical objects that have a spiral shape, first discovered by Lord Rosse in Ireland in 1844, and their nature was a mystery. Some thought that spiral nebulae were just that, nebulae, collections of gas and dust or small clusters of stars that were part of our own stellar system. Others proposed that spirals are external galaxies, vast collections of stars like our own Galaxy, and very distant from us (this latter hypothesis was known as the "island universe" theory).

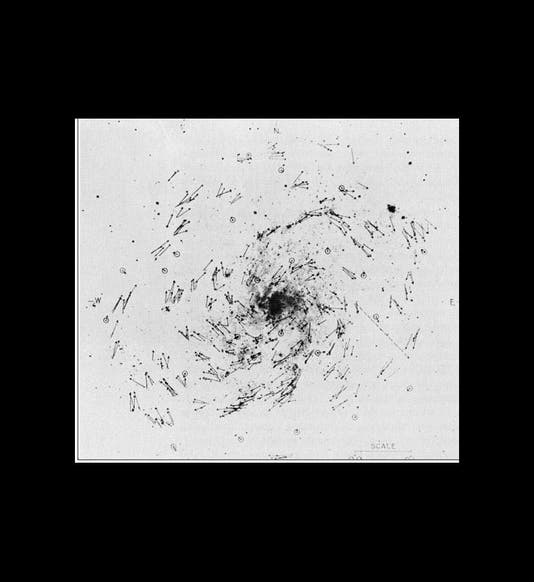

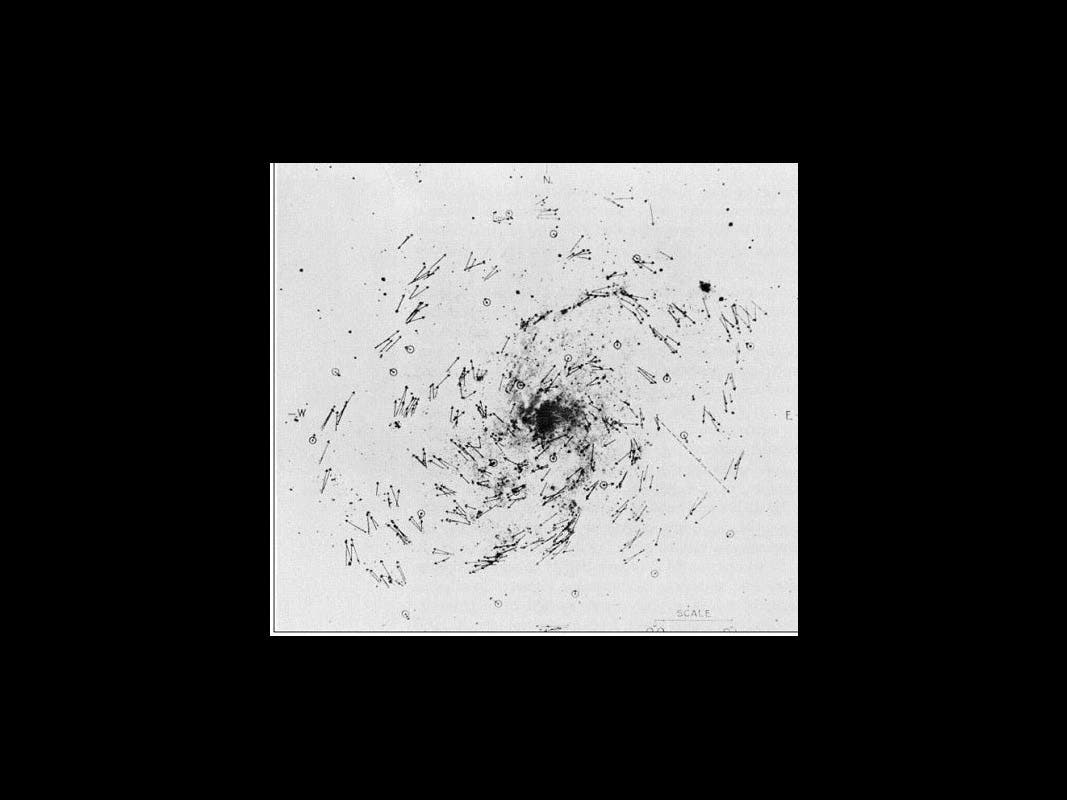

Van Maanen took photographs of various spirals, such as M33 and M81, and using a blink comparator (the same kind of instrument with which Clyde Tombaugh would soon discover Pluto), van Maanen claimed to detect the motion of individual stars. Above we see one of his stellar motion charts of M33, with the stellar velocities indicated by short arrows (first image). These motions were comparatively large, indicating that the spirals would complete a rotation in a fairly short time, a thousand years or so. Consequently, there was no way these spirals could be large and distant, or else the stellar velocities would be impossibly large. Van Maanen published papers in 1916 and 1921 and convinced most of the astronomical community that the island universe hypothesis was untenable. In the Great Debate of 1920 between Heber Curtis and Harlow Shapely on the nature of spirals, Harlow Shapley opposed Heber's island universe, citing van Maanen's measurements as evidence. And when, shortly thereafter, Edwin Hubble claimed that M31 was an external galaxy, far beyond the confines of the Milky Way Galaxy, van Maanen's rotation rates were used against Hubble.

Hubble persisted, and by the 1930s it was clear that he was right, and that spirals are truly external galaxies, which meant that van Maanen's high rotation rates were simply wrong. Shapley was furious with van Maanen, as he had stood by van Maanen and defended the reliability of his measurements. No one to this day knows why van Maanen's measurements were so much in error, but it was probably the result of his trying to measure motions that were simply beyond the threshold of observability. Needless to say, van Maanen does not have a space telescope named in his honor.

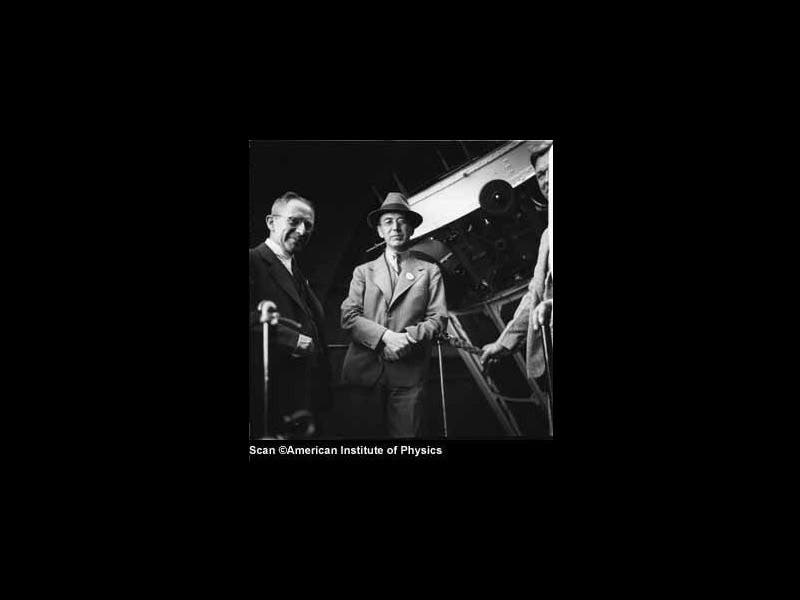

In the photograph above, van Maanen is standing at the left, next to Bertil Lindblad, a Swedish astronomer who in the late 1920s tried and failed to confirm van Maanen’s measurements (second image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.