Scientist of the Day - Agnes Catlow

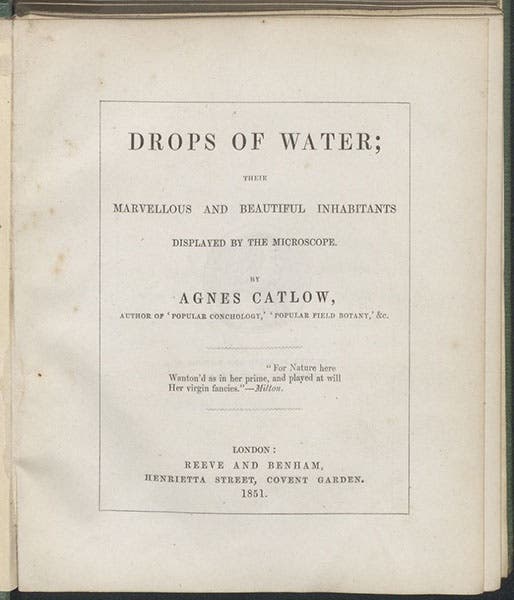

Agnes Catlow, an English popular science author, died May 10, 1889, at the age of about 83. We don't have a portrait of Ms. Catlow, and we don’t’know much about her, except that she was born in Nottinghamshire, died in Surrey, and wrote and published several science books for the general public in the 1840s and 1850s. Popular science writing was just opening up as a vocation for women in England in the 1840s, although there were a few women, such as Margaret Bryan, who were so engaged earlier in the century. Catlow's first success was a book on shells called Popular Conchology (1842), which went through several editions. However, since we do not have this work in any form in our collections, we are going to discuss here her second major publishing effort, of which we do own a copy, a book called: Drops of Water: Their Marvelous and Beautiful Inhabitants Displayed by the Microscope (1851).

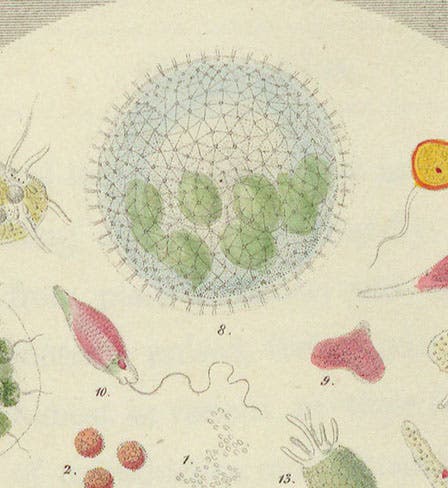

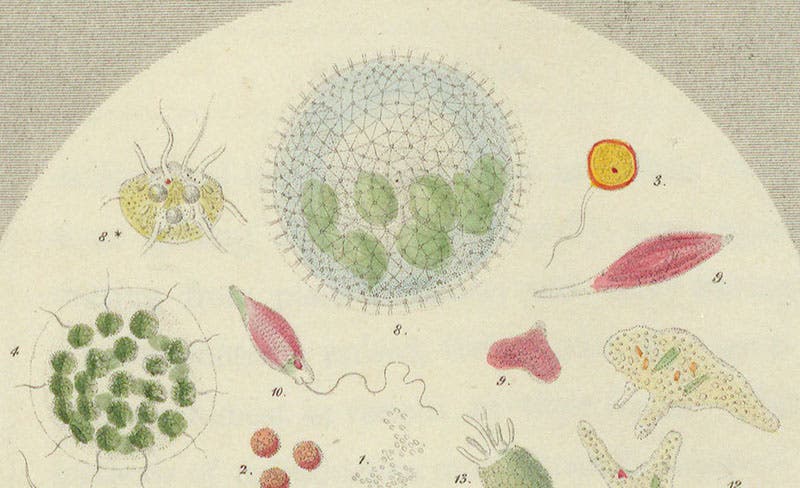

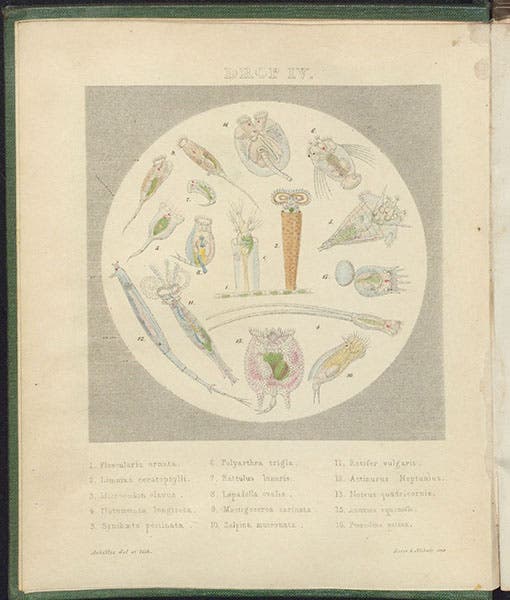

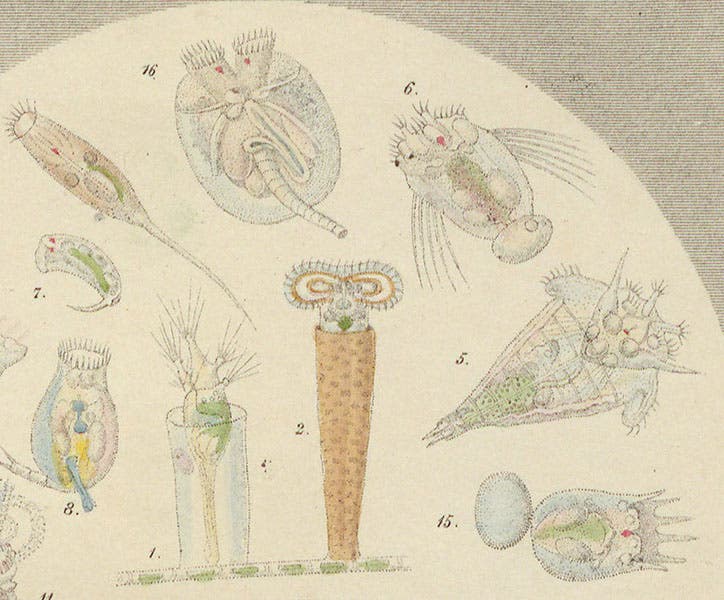

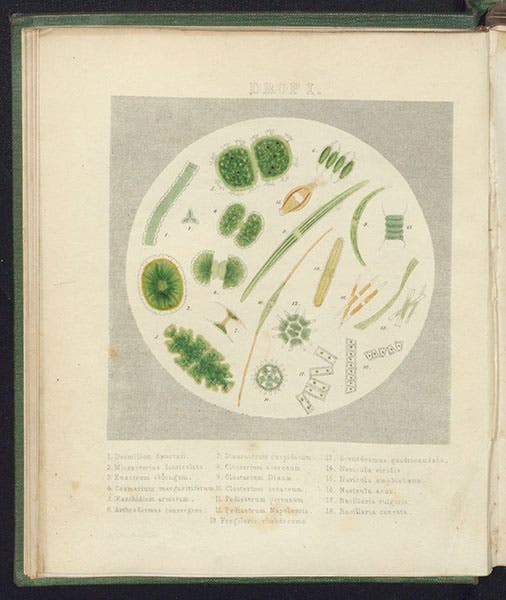

This is a delightful book, intended for the reader who has just acquired a microscope and wants to know what to do with it. Catlow organized her book around four "drops," each of which is illustrated by a hand-colored lithograph that contains a dozen or so "animalcules," or infusoria. There is a chapter devoted to each drop, where Catlow explains what each creature is and what you will see it do if you observe it through a microscope. Her prose is eager and friendly, but she would not be considered a stylist – I looked for a descriptive paragraph that was especially well-written so that I could quote it here, and I did not find one. There is nothing wrong with the way she writes – everything is quite clear and occasionally exciting – it is just that Catlow is not a master of the well-turned phrase. But then, impressing the reader with eloquence was hardly her intent.

Catlow knew well the most recent works by authorities on microorganisms, especially Christian Ehrenberg, whose Infusionsthierchen als volkommene Organismen (Infusoria as Perfect Organisms, 1838) was certainly right on her worktable when she wrote this book and whom she frequently acknowledged in her text. But Catlow was clearly intimately familiar with all the microorganisms she wrote about. For example, she described the behavior of Vorticella, which attach themselves by a tendril to a plant and then float away to feed; if they are alarmed, they can contract a fiber in the tendril, and do it so fast that you can't even see them move – one moment they are there, the next they are gone. That is not the kind of thing you would learn from Ehrenberg's book (although you might well learn it from hers)

The lithographs in Catlow's book are each signed "Achilles del et lith." ("Achilles drew and lithographed this"). It is not clear (to me) who "Achilles" is. I could find no mention of a 19th-century illustrator named "Achilles" anywhere. It is possible that this is a pseudonym for Catlow – we know she had artistic talent and provided illustrations for other books. If she actually drew and lithographed the plates for Drops of Water, presumably she would have mentioned that somewhere in the book, and I did not find such a mention. But then, I was reading the paper copy, and not a searchable version, and might have missed it.

Several years ago, we published a post on Mary Ward, another Victorian-era author of a popular book on microscopy. But Ward's book followed the model of Robert Hooke, looking at scales on butterfly wings and dust mites and such, and had only a single illustration of microorganisms. Catlow had her eye only on infusoria, on what you can see in a drop of water, or four drops of water, if you choose your drops carefully.

Our copy of Drops in Water has now been scanned and is available online, if you would like to look and read for yourself.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.