Scientist of the Day - Alan Turing

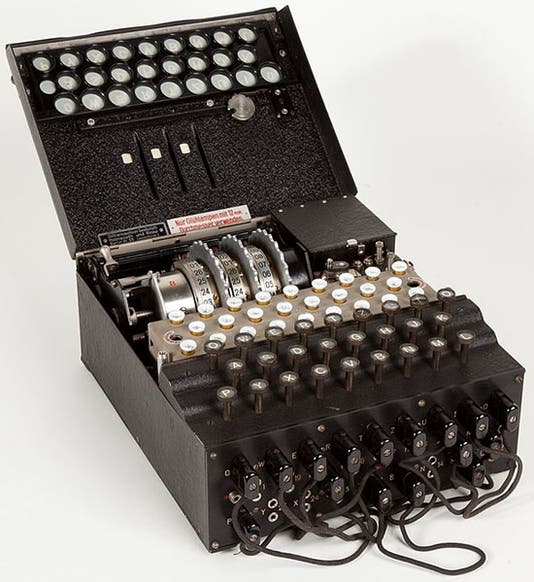

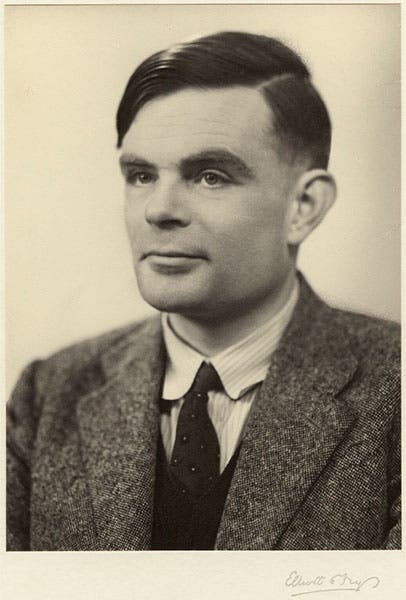

Alan Turing, a British mathematician, was born June 23, 1912. Turing is often called the "father of the modern computer," although several others, especially John von Neumann, might be equally deserving of the title. A fellow at King's College, Cambridge, Turing by 1936 had already proposed the idea of a universal computer – a Turing machine, a logical device that could perform any operation that was calculable. But when war threatened in 1938, Turing joined several other King’s mathematicians at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire (third image), where their task was to crack the codes of the German military. As I am sure almost everyone knows, German cryptographers had developed a powerful cipher machine called the Enigma (first image), which would produce an encrypted message that could only be read by another Enigma machine – assuming, that is, that all the rotors, wheels, and punchboard wires were properly set. Enigma encryptions were considered by the Germans to be unbreakable, and many British cryptographers tended to agree with that assessment.

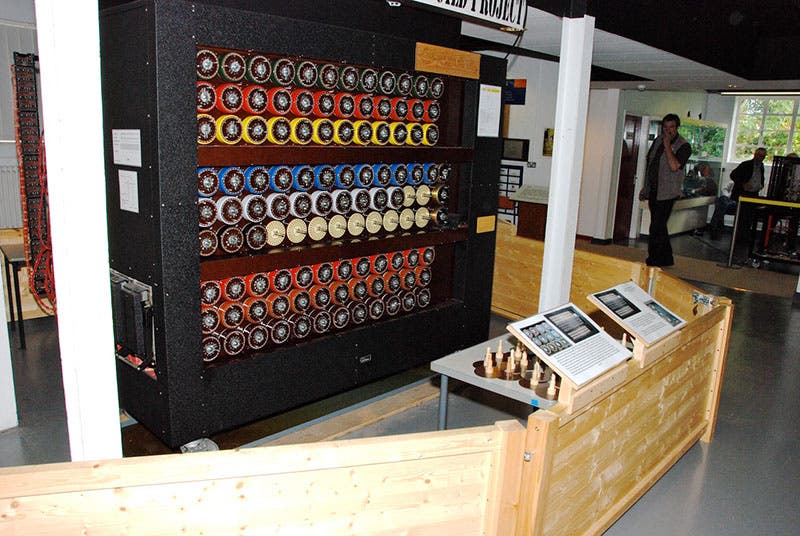

Turing was not a cryptographer, but a theoretical mathematician, a logician, and one of his most unusual traits, for a theorist, was to believe that working on practical applications of mathematical logic was a worthy activity. He was totally absorbed by the effort to crack the Enigma ciphers. By 1941, the English had succeeded. If you have seen the film, The Imitation Game (2014), in which Turing is deftly played by Benedict Cumberbatch, you learned there that Turing almost singlehandedly built the bombe – that mechanical colossus with all the rotating cogs and cams that took in an Enigma cipher, clanked and churned, and spit out the clear text. We show here a replica of the bombe on display at Bletchley Park (fourth image). In truth, many others were involved as well, and the idea of the bombe actually came from the Poles, who created a preliminary machine, the bomba, in 1938, which Turing learned about before Poland was invaded by the Nazis. But Turing did play an important role as the first head of “Hut 8”, which attacked the problem of the German naval codes, and Hut 8 did manage to break enough ciphers to end the U-boat carnage in the Atlantic and shorten the war by several years, or so it is estimated.

Aside from the universal Turing machine and the bombe, Turing has two more feathers in his cap that should be mentioned. In 1946, Turing was the first to propose that a computer might have its program written in the same language as its data, so that it could be easily re-programmed. This was a novel idea, since the few computers constructed to date, such as the ENIAC in the United States, had paper tape programs to go with their vacuum-tube brains. The first programmable computer was built in Manchester in 1948, where several other King’s mathematicians, including Turing, had moved after the War.

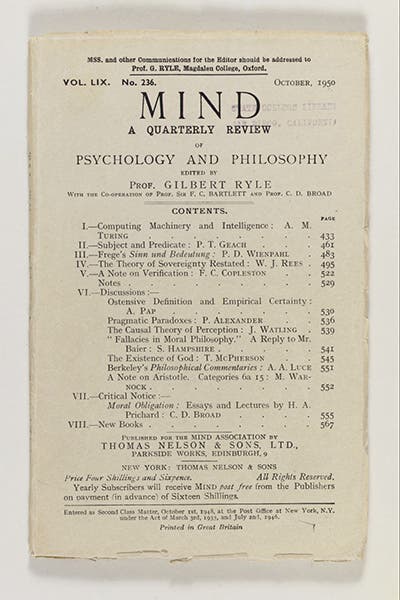

Turing’s other great insight was to invent the field of artificial intelligence. In 1950, he published a paper in the journal Mind, in which he asked whether computers might eventually be able to think (below is the cover of the October 1950 issue, with Turing’s name at the top of the table of contents). Turing concluded that indeed they might. This was a rather shocking notion at the time, but Turing’s idea was that if a computer can do anything that is calculable, and if the human brain thinks by doing calculable logical operations, then there is nothing the brain does that a computer, in theory, could not replicate. It was in this paper that Turing proposed the now-famous Turing test, in which an interrogator remotely converses with a computer and a human and tries to tell them apart from their responses. If you cannot tell the human from the computer, the computer has passed the Turing test (the “imitation game”) and is a thinking machine. Another excellent film, Ex Machina (2014), employed the Turing test as a major plot element in its tale of artificial intelligence.

Turing’s life had a sad end, as you know if you saw The Imitation Game. Turing was a homosexual at a time when homosexuality was a criminal activity in Britain. When his sexual proclivities were discovered in 1952, he was convicted of “gross indecency.” He avoided prison only by agreeing to a kind of chemical castration, which seems to have affected his ability to work, and in addition, cost him his top-secret clearance. Two years later, he took his own life by ingesting cyanide (although some think that that his death might have been accidental poisoning). He was 42 years old. It was not until 2013 that Turing was officially pardoned by the Queen, which means it took 60 years to exonerate one of Britain’s greatest war heroes and most brilliant mathematicians for a crime that should never have been a crime in the first place.

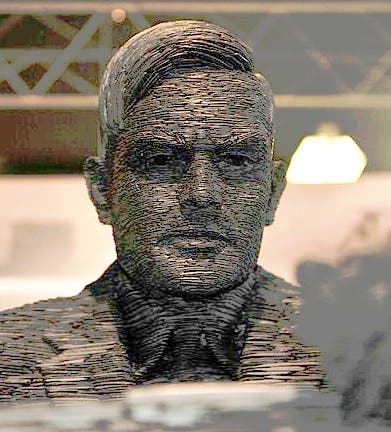

A statue of a seated Alan Turing, fashioned in slate by Stephen Kettle, was installed at Bletchley Park in 2007; above we see a detail of just the head. You can see the complete statue here.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.