Scientist of the Day - Albert Bierstadt

Albert Bierstadt, a German/American landscape artist, was born Jan. 7, 1830. Arriving in the US as a 1-year-old, he took up painting early, and except for several years of study back in Germany, he spent the rest of his life in this country. Bierstadt became associated with the Hudson River School of American landscape painting in the 1850s; in 1859, he went west as part of the Lander survey. Frederick Lander had built a cutoff to the Oregon trail (called the Lander Road) in western Wyoming in 1857-58, and he was returning to do additional survey work and invited several artists to come along. The experience changed Bierstadt's life, as he began painting grand western landscapes, thus founding (with Thomas Moran and several others) what came to be called the Rocky Mountain School of landscape art.

Bierstadt did most of his painting at the 10th Street Studio Building in New York City, where in 1859, Frederic Church had painted and exhibited The Heart of the Andes to great acclaim. Bierstadt’s first notable success was a painting called The Rocky Mountains, Lander's Peak, which he completed in 1863 and exhibited that same year (first image). It was just as sensational as Church’s painting. Lander’s Peak is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and I remember seeing it ten years ago, when the Met was remodeling, and they had moved Lander's Peak and several other monumental Hudson River landscapes into one temporary room, and so it was hanging right next to Church's Heart of the Andes. They formed quite an impressive pair, I can tell you.

Bierstadt went back West on a second expedition in 1863, teaming up with a photographer and writer, Fitz Hugh Ludlow. Bierstadt went through Colorado this time. Just west of Denver, they encountered a 14,000-foot peak which they named Mount Rosalie, after Ludlow’s wife, and Bierstadt was supposedly the first to climb it. More importantly, he painted another landscape back in New York City, centered on the mountain, which is called A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie (second image). The painting was finished in 1866, by which time Rosalie had divorced Ludlow and married Bierstadt, and it is now in the Brooklyn Museum of Art. As you can probably tell, Bierstadt did not make photograph-like reproductions of places he visited; rather, he used his sketches to create sublime vistas that one would never find in nature, but which were nevertheless testaments to the grandeur of the West.

Bierstadt and Ludlow eventually reached California and Yosemite Valley. Of the several large landscapes of Yosemite that Bierstadt painted, perhaps the grandest is Domes of the Yosemite (1867). The painting was commissioned and sold for $25,000, an enormous sum at the time. When the purchaser went bankrupt and died, the painting was acquired (for a mere $5000) by Horace Fairbanks, and it became the centerpiece of the gallery he established, the Athenaeum Art Gallery in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, where it is still the centerpiece. We show here a view of the painting in place, before it was recently restored (third image). You can see the painting after restoration at this link.

And since we have room, we show one more Bierstadt landscape, a later one called Estes Park, Long Peak (1876), which is in the Denver Art Museum, on loan from the Denver Public Library (fourth image). Bierstadt’s paintings are often criticized as overly Romantic and reeking of Manifest Destiny, but we should remember that these are the product of the 19th century, the age of Romanticism, and I don’t see how anyone can stand in front of Landers Peak at the Met and not be filled with awe.

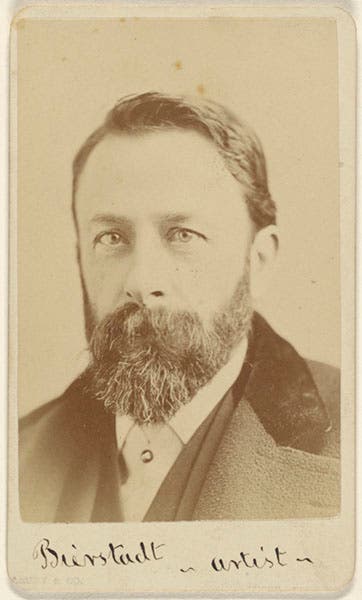

Portrait of Albert Bierstadt, carte de visite, undated (J. Paul Getty Museum)

The portrait we include is from a carte de visite at the J. Paul Getty Museum (fifth image). Bierstadt’s wife Rosalie died in 1893, after a 17-year battle with tuberculosis, with her husband at her side throughout the ordeal. Bierstadt died in 1902, at age 72.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.