Scientist of the Day - Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein, a German-American physicist, died on Apr. 18, 1955, in Princeton, New Jersey, at the age of 76. Einstein is the one scientific name that everyone knows, and it has been that way for the past hundred years. Seven years ago, we wrote a general post on Einstein, in which we briefly mentioned his early work on Brownian motion, the photoelectric effect, and special relativity, and his later paper on general relativity, and then devoted most of the remaining space to presenting three original portraits of Einstein that we have in our Library – two paintings and a bronze bust. We have yet to discuss his scientific work in any detail, and we will have to do that soon.

Today, however, I would like to present the human side of Einstein, mostly in his own words. Many years ago, I put together a 2-minute radio commentary on Einstein, which I am guessing hardly anyone heard. I have always been fond of this piece, so I resurrect it today, as a way of honoring the twentieth century’s greatest scientist, and arguably one of its greatest human beings, on the 68th anniversary of his death.

In 1936, a young Sunday school student wrote Einstein a letter, asking whether scientists pray. Einstein replied:

Scientific research is based on the idea that everything that takes place is determined by laws of nature, and therefore this holds for the actions of people. For this reason, a research scientist will hardly be inclined to believe that events could be influenced by prayer… by a wish addressed to a supernatural being. However, it must be admitted that our actual knowledge of these laws is only imperfect and fragmentary, so that, actually, the belief in the existence of basic all-embracing laws in Nature also rests on a sort of faith. All the same, this faith has been largely justified so far by the success of scientific research. But, on the other hand, everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the Universe – a spirit vastly superior to that of man, and one in the face of which we, with our modest powers, must feel humble. In this way, the pursuit of science leads to a religious feeling of a special sort, which is indeed quite different from the religiosity of someone more naïve.

This is a remarkable document, not least because Einstein, a world-famous figure, wrote it by hand to a 12-year-old girl he had never met. It reveals an Einstein we do not often see described. Einstein was one of the most humble, spiritual, and supremely moral human beings that one could hope to encounter, and yet he stood completely outside of any institution that seeks to regulate our moral or spiritual lives. His morality was not legislated, or mandated, but forged deep within his inner being.

In 1950, Einstein received a letter from a Brooklyn minister, asking for any kind of personal testament that he could treasure. Einstein replied:

The most important human endeavor is the striving for morality in our actions. Our inner balance and even our very existence depend on it. Only morality in our actions can give beauty and dignity to life. To make this a living force and bring it to clear consciousness is perhaps the foremost task of education. The foundation of morality should not be made dependent on myth nor tied to any authority, lest doubt about the myth or about the legitimacy of the authority imperil the foundation of sound judgment and action.

In an age when we often let institutions and political parties determine our views on many matters, Einstein teaches us that there are other, and perhaps better, ways to realize our humanity.

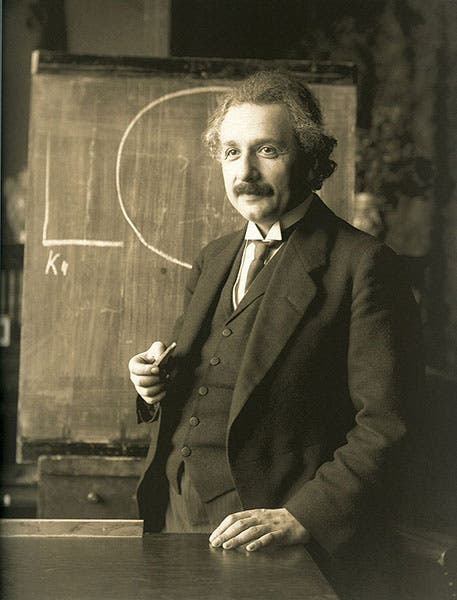

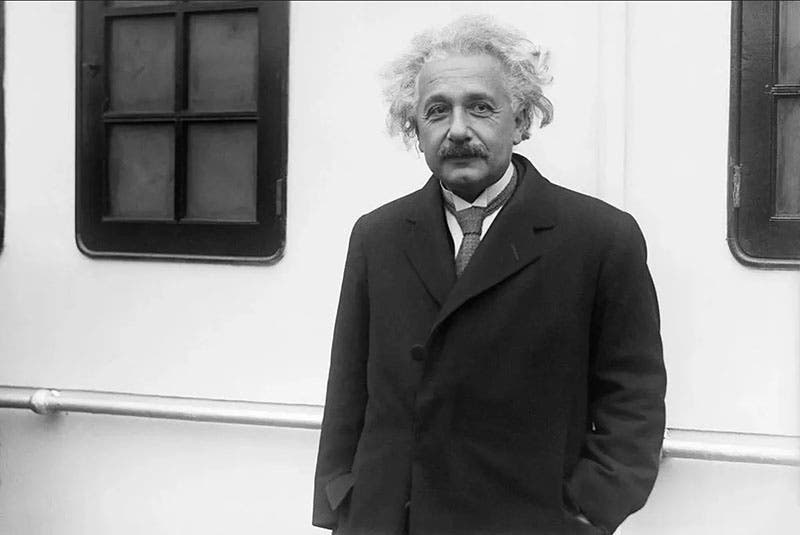

You can find a selection of letters sent to Einstein by children from around the world, and a few of Einstein’s replies, in Dear Professor Einstein: Albert Einstein’s Letters to and from Children (Prometheus Books, 2002). The portraits we include here are two of my favorite photographs, capturing Einstein at the height of his intellectual and moral powers, in 1921, the year of his Nobel Prize (first image), and 1931, two years before he emigrated to the United States (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.