Scientist of the Day - Alexander Dallas Bache

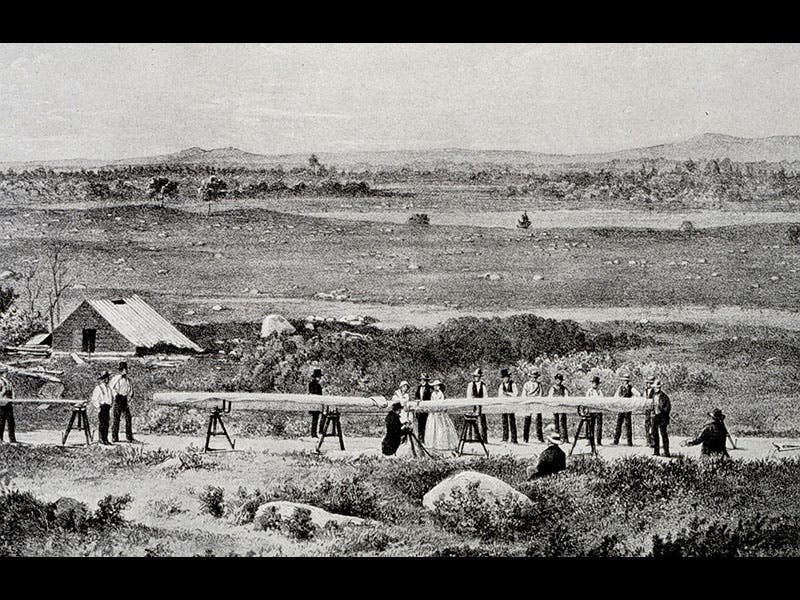

Alexander Dallas Bache, an American scientist and administrator, was born July 19, 1806. Bache was the great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin, graduated from West Point, taught natural philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania for 15 years, and then, in 1843, was appointed to head the United States Coast Survey. Bache proceeded to fashion the Survey into the largest and most successful scientific institution of the century. The Survey mapped the entire Eastern seaboard and much of the Pacific coast during Bache's lifetime. Bache’s staff charted in great detail the Gulf Stream (which had been discovered by Bache's great-grandfather); they commissioned special iron-hulled steam ships that were much more efficient for deep-sea sounding than conventional sailing vessels. The Survey established six base lines from Alabama to Maine, to which all other measurements could be correlated. The photo above (third image) shows Bache and his team laying out the last of these, in Washington County, Maine, in 1857. This base line, the only one that survives, is 5.4 miles long; it was re-surveyed using GPS equipment about 25 years ago and was found to be accurate to within one half-inch.

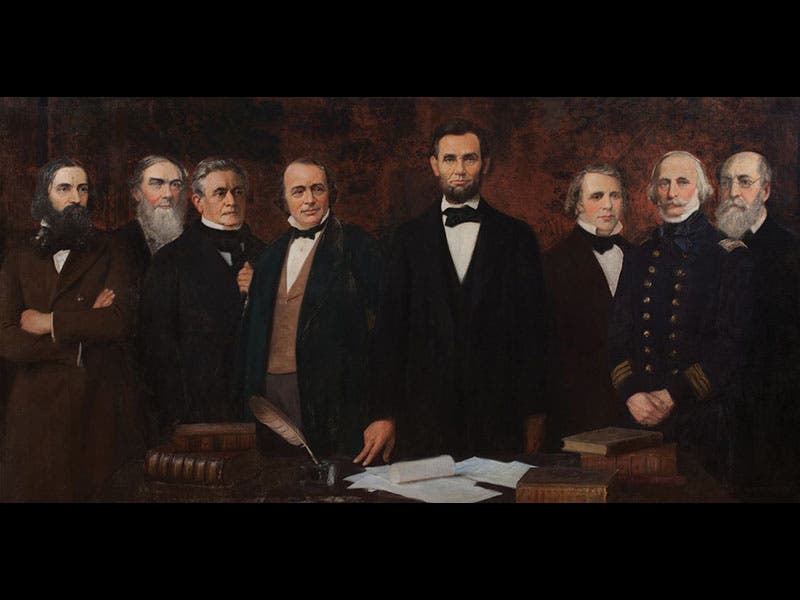

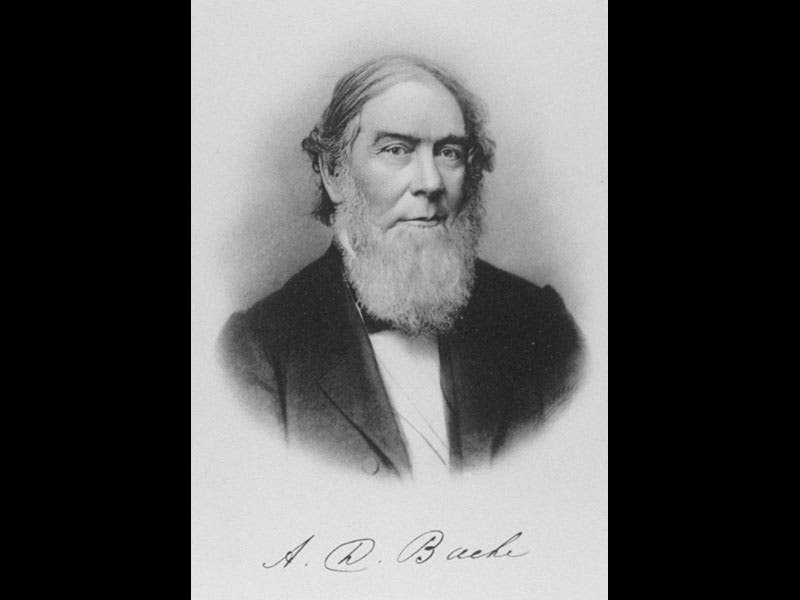

Bache was apparently a master administrator and it is hard to find contemporaries who were critical of him or his work. When the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) was founded in 1863, Bache was not only a charter member, but also the first president. The current NAS building has a painting hanging in the board room that purportedly records the signing of the charter of the NAS (although it was painted 60 years after the fact, by Albert Herter). It provides a group portrait of the cream of American science at the time of the Civil War (first and second images). Abraham Lincoln of course is convening the group, and Bache is portrayed as well, second from the left, with the full beard. Another portrait (fourth image) shows Bache in greater detail.

Historians have often wondered why Bache faded from prominence after his death in 1867, while those of lesser accomplishments, such as Louis Agassiz (fourth from the left in Herter's portrait) were exalted by the public. One school of thought blames Bache's eclipse on his approach to natural history; quite simply, he had no use for it. Other surveys, such as the Pacific Railroad Surveys of the 1850s, collected specimens of animals and plants and commissioned chromo-lithographed landscapes of areas visited, which, when published, greatly impressed the public. Bache didn't collect things--he measured them. He was a mathematician who thought that, to understand the ocean, you collected data--about magnetism, prevailing winds, ocean currents, ocean-floor depth, etc.--and you drew out patterns from this data. You didn't try to reduce the ocean to an aquarium, which is the approach Agassiz would have taken. But the public likes aquariums, and doesn't much care for graphs and tables, and so Bache never seems to have established much of a public persona. That is too bad; he was one of the great scientific administrators of the century and deserves to be better known.

Bache is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C (fifth image). If there is a statute or bust of Bache in any public place, we are unaware of it.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.