Scientist of the Day - Alexander Fleming

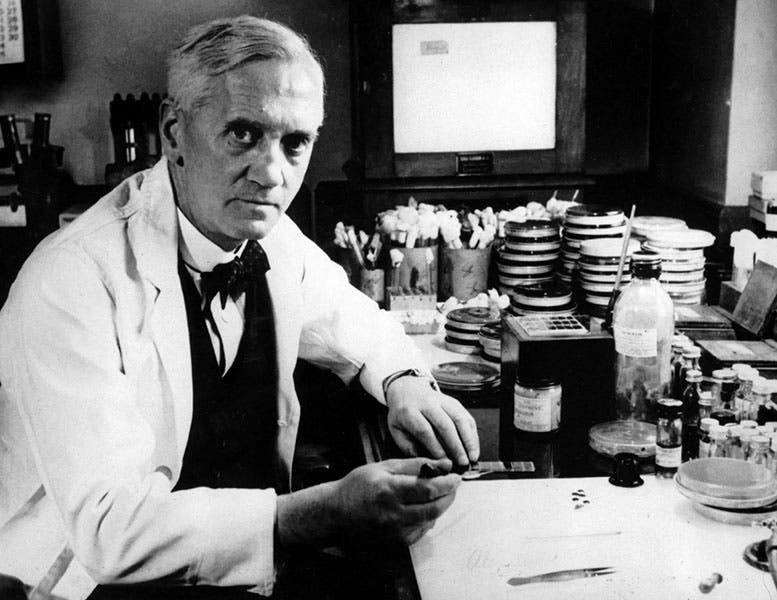

Alexander Fleming, a Scottish bacteriologist, died Mar. 11, 1955, at age 73. Fleming is about as famous as a scientist can get. Nearly everyone learns in secondary school that Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928 and perhaps that he shared a Nobel prize for this discovery in 1945. He is on many lists of the hundred greatest scientists of all time.

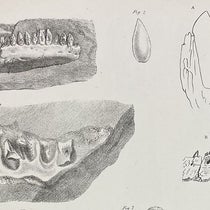

However, historians generally recognize that Fleming's role in the penicillin saga has been greatly overblown, and of the four men involved in the creation of the first antibiotic, Fleming was probably the least important. Fleming did discover that the bread mold Penicillium, which quite by accident had infiltrated one of his petri dishes, has anti-bacterial properties, and for that he gets full credit, because the incident could easily have been overlooked by someone less vigilant. He was able to use it to cure several cases of eye infection, and he did publish several papers on the antibiotic properties of penicillin, papers which were universally ignored, which was not Fleming’s fault.

But Fleming was unable to isolate penicillin from the mold (although he did name it in 1929), and although he continued to work on it until 1939, he was never able to create a useful antibiotic from bread mold, and really didn’t think it could be done. It was Howard Florey, an Australian, then working at the Radcliffe Infirmary at Oxford with Boris Chain, who discovered in 1940 how to isolate penicillin and mass-produce it, and they had the vital help of a student, Norman Heatley. By the end of the War, billions of units of penicillin were being produced in Great Britain and the United States, and Fleming played no role whatsoever in this medical milestone. Florey and Chain shared the Nobel Prize with Fleming in 1945, but poor Heatley, whose contribution proved indispensable, was left out, as someone had to be, since a Nobel prize has a limit of 3 co-recipients.

In the 1940s, Fleming was modest enough about his role in the success of penicillin, and he himself created the term “the Fleming myth” to refer to the inclination of the press to give him sole credit for the wonders of penicilliin. It was not his fault that he was happy to talk to the press, while Florey refused to allow his team to do so (there was a war going on). Florey was charitable enough about Fleming’s role in 1945, willing to give Fleming credit for the 1928 discovery. But Florey later grew quite exasperated at Fleming's inclination to take more credit than he was due for the mass production of penicillin. It is a good thing that Florey did not live to see Fleming included by Time Magazine in 1999 on their list of the 100 most important men of the century, and himself and the rest of his team excluded. The Fleming myth is still going strong.

Australians get quite indignant about the attention given to Fleming and the neglect of Florey. We once wrote a post about Florey in which we discussed this in a little more detail. Someday I will write about Heatley, the one left out of the Nobel prize, who was only a grad student in 1940, but who by general agreement was the most essential investigator of the four, because of his skill in improvising and setting up lab equipment for the extraction of the antibiotic from the mold.

Often forgotten in the debate over the Fleming myth is the fact that Fleming had one other major discovery to his credit, that of lysozyme, an enzyme that has anti-microbial properties, and is present in tears, salliva, and mucus. It is said that he discovered lysozyme when his nose dripped onto a bacterial culture in 1921. Indeed, it has been often noted that Fleming kept a very messy lab, and that most of his discoveries were a result of his neglect in protecting his cultures. However, this required that he be perceptive enough to notice when something went wrong, and that he certainly was. He was one of the classic examples of the adage: “Chance favors the prepared mind.”

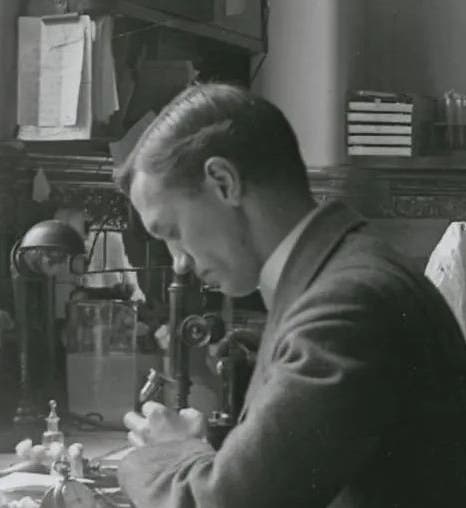

There is an Alexander Fleming Museum in St. Mary’s Hospital in London, where Fleming discovered both pencillin and lysozyme. Their website says that the lab has been restored to its 1928 condition, and from the photograph (fourth image), it looks like they captured Fleming’s lack of orderliness quite well.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.