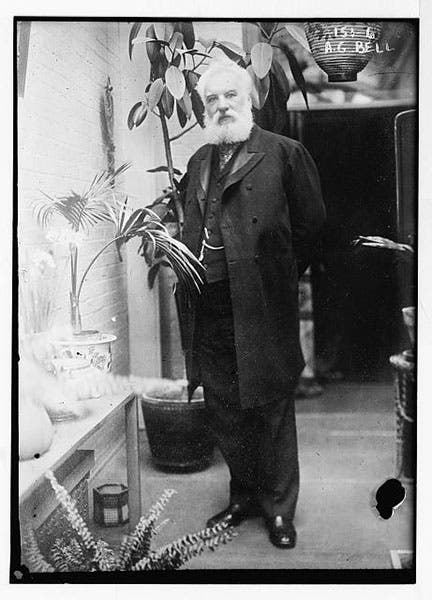

Scientist of the Day - Alexander Graham Bell

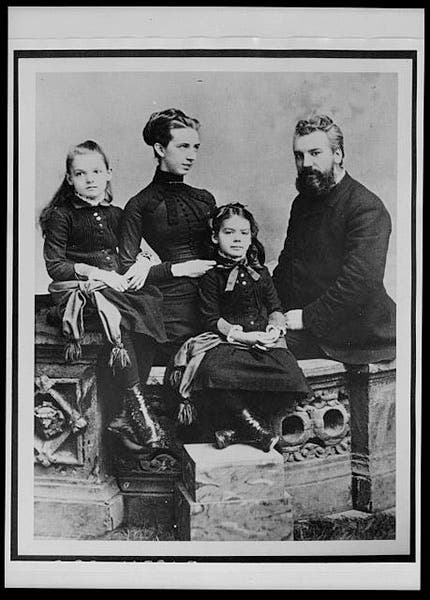

Alexander Graham Bell, a Scottish/American/Canadian inventor, was born Mar. 3, 1847, in Edinburgh. Bell's father and grandfather were elocutionists and phoneticians, with interests in teaching speech to the deaf, and Bell developed similar interests, especially after his mother became deaf as a result of an illness. Both of Bell’s brothers died of tuberculosis in the 1860s, and Alexander’s health was not good, so the family decided to move to Canada for health reasons in 1870. They bought a farm in Brantford, Ontario, and the father taught there and was invited to teach in Boston. Instead, he recommended his son, and Alexander taught elocution and Visible Speech in Boston in the early 1870s. Two of his pupils – George Graham and Mabel Hubbard – had wealthy parents, who would support several of Alexander’s early inventing projects. Alexander would marry Mabel, and thus Hubbard became his father-in-law, and continued as his patron.

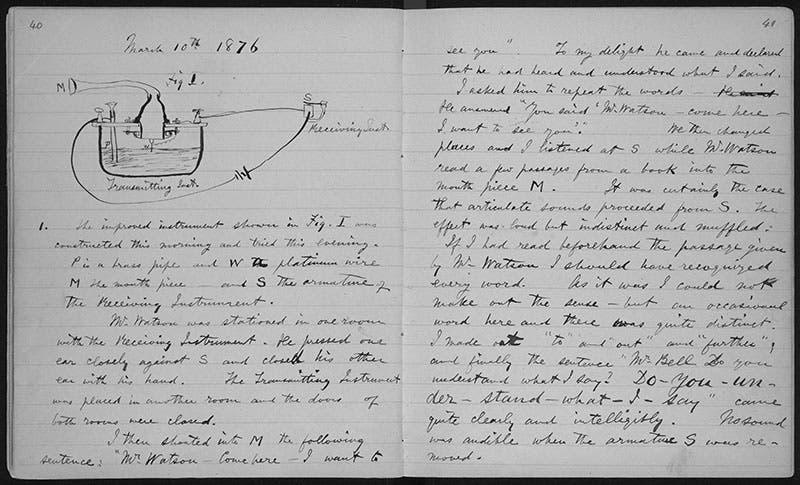

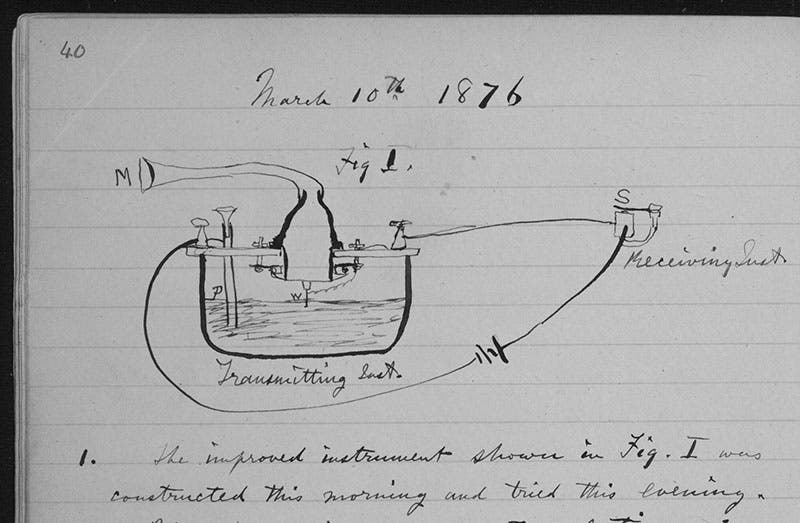

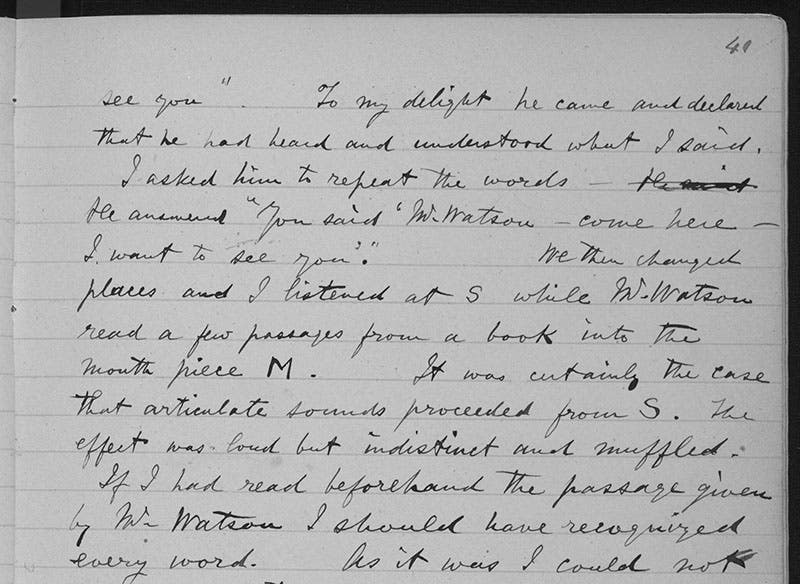

Although Bell was not mechanically adept, like that other famous inventor, Thomas Edison, he was brimming over with ideas. One interest of the early 1870s was “harmonic telegraphy” – a much-needed technology for sending multiple and simultaneous messages over a telegraph line. Bell received financial backing for this project from Graham and Hubbard. It was while working on this problem that Bell came up with an idea for transmitting the human voice over a telegraph line. Bell was provided with funds enabling him to hire a gifted assistant, Thomas A. Watson, with whom he worked on developing suitable transmitters. Quite a few inventors, including Edison and Elisha Gray. were working on the same problem, and when Bell’s lawyer submitted Bell’s U.S. patent application on Feb. 14, 1876, he beat Gray to the punch by only a few hours. Bell’s application was approved on Mar. 3 and the patent issued on Mar. 7. Three days later, on Mar. 10, 1876, Bell spoke the famous lines into his transmitter, directed to his assistant in another room: "Mr. Watson – Come here – I want to see you." The notebook that Bell kept, and in which these words are recorded, is intact and in the Library of Congress – we show the page opening for Mar. 10, 1876 (third image), and details of the transmitter used that day (fourth image) and the famous words heard by Watson (fifth image). This transmitter, with vibrations passing through a liquid, is quite similar to that proposed by Gray in his submitted patent caveat of Feb. 14, leading many to suggest, then and now, that Bell stole the idea from Gray. But since Bell had worked with a variety of transmitters for years, including liquid ones, and since all his later transmitters were mechanical-electrical, the charges have never stuck. Certainly, they were never successful in court.

Bell demonstrated his telephone successfully at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia; the transmitter from that demonstration can be seen in the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. (first image). Much later, in 1892, he took part in a telephone call opening a line from New York City to Chicago (sixth image). By that time, however, he had long lost interest in telephony, partly because of the legal battles in which he was continually engaged. Hundreds of lawsuits, mostly disrupting the patent, were filed between 1876 and 1890. The Bell corporation won every one of them.

Bell meanwhile was engaged in other projects. He set up his own school for the deaf for several years. He met and encouraged the young Helen Keller. He became interested in hydrofoils, and kites, and heavier-than-air-craft. He spent much of his newly acquired patent-wealth helping other scientists and inventors. Bell gave $500 to Albert Michelson to undertake his famous ether experiments (with Edward Morley) of 1887. And he gave $5000 to Samuel P. Langley, who was attempting to built his own airplane at the same time as the Wright Brothers. The kite experiments he conducted himself, at the family estate in Nova Scotia.

Bell also played an important role in helping scientists communicate with each other, and with the public. He founded the journal Science, which would later become the official organ of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), and the American equivalent of the British journal Nature. He was one of the founders and an early president of the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., and it was Bell’s idea that its journal should not be the typical dry scientific serial, but should be copiously illustrated and written in the language of the general reader.

Bell died on Aug. 2, 1922, at the ag of 75, from complications due to diabetes. He was buried on top of the mountain at his estate at Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where he lived for the last 35 years of his life, and where there is now a museum in his honor. Bell is a national hero in Canada, perhaps more so than in the United States.

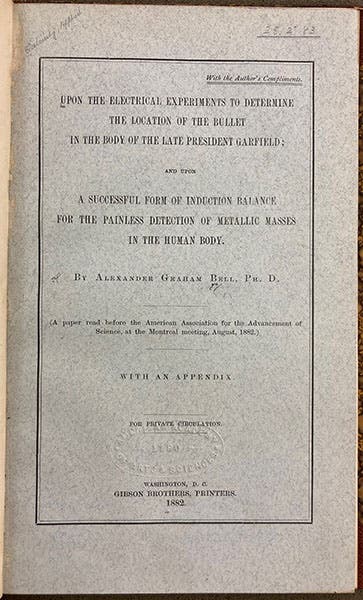

Title page of Upon the electrical experiments to determine the location of the bullet in the body of the late President Garfield: and upon a successful form of induction balance for the painless detection of metallic masses in the human body, by Alexander Graham Bell, privately printed, 1882 (Linda Hall Library)

We have an interesting Bell publication in our collections, written to record an event that is often omitted from short biographies of Bell. After President James Garfield was shot by an assassin in the summer of 1881, and doctors could not locate the bullet, Bell invented a metal detector for that purpose, and he was allowed to try to find the bullet. His attempts were not successful, for reasons that had nothing to do with the instrument, and Garfield died 79 days after he was shot. A year later, Bell gave a talk to the AAAS at their meeting in Montreal in 1882, and he privately printed his remarks and distributed them. We have the copy that he presented to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston. It was called Upon the electrical experiments to determine the location of the bullet in the body of the late President Garfield: and upon a successful form of induction balance for the painless detection of metallic masses in the human body. We show you the front cover, which doubles as a title page (eighth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.