Scientist of the Day - Alexander Keiller

Alexander Keiller, a Scottish businessman and archaeologist, was born Dec. 2, 1889. Keiller amassed a modest fortune by managing the family business, which happened to be making and marketing James Keiller & Son Dundee Orange Marmalade. But Keiller had a lifelong interest in archaeology, and in 1925 he poked for the first time into the environs of Avebury, a collection of prehistoric stone circles just north of Stonehenge.

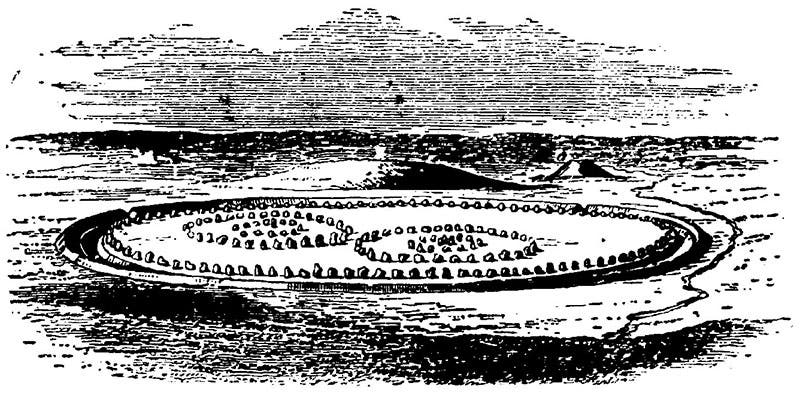

Avebury had been erected around 2600 B.C.E. (we now know), as a huge embankment and ditch, with a large stone circle just inside the ditch (the largest Neolithic stone circle in the world, in fact), and then two smaller circles of stone within the outer circle. We show above a 19th-century drawing that attempted to reconstruct the Avebury circles. Originally there had been a hundred stones in the outer circle; several dozen more in each of the inner circles, and scores more along a lengthy entrance avenue. But in the 14th century, as locals became wary of these pagan monoliths lurking in their Christian midst, many of the stones were buried out of sight, and a few were broken up. Avebury was still impressive when John Aubrey and William Stukeley separately mapped the area between 1660 and 1730, even with lots of stones missing, but locals continued to remove stones or demolish them in the years following, so that by the early 20th century, Avebury was a sorry-looking site. And it did not help that the village had spread out through the two inner circles, or that copses of trees had moved in as well, and that the ditch was brimming with trash and debris.

Keiller did not take a serious interest in Avebury until 1934, but then he got hooked. He started buying up the land on which Avebury sat, spending his marmalade money on megaliths, until eventually he owned it all. He removed shanties and shacks and often entire farmhouses, if they infringed on the circles. He cleaned out the debris. And he went looking for the missing stones. Since the stones are very heavy, Keiller reasoned that they would have been buried close to their original locations, and he was right. He started excavating along Kennett Avenue, the long stone-lined entrance to the circles, and soon he had located and re-erected most of those stones. Just below is a modern view of the avenue of stones. Then he worked his way around the circles, inner and outer, until the War intervened. At which point, Keiller sold his acquired property at cost to the National Trust. If you go to Avebury today, most of what you see is the result of the work of Keiller and his crews. Little more has been done since Keiller died, sixty-six years ago, except to incorporate Avebury into a World Heritage site that includes Stonehenge.

One of Keiller's more sensational finds was the so-called Avebury "barber surgeon". As he attempted to raise one large stone, he found underneath the skeleton of a man accompanied by several tools, one of them a surgeon's probe, and a purse with several coins dated around 1320. The supposition was that when the villagers were toppling the stone for burial in the early 14th-century, it fell upon our hapless victim, and since his fellow townsfolk could not extract him, they left him be. Keiller raised and replanted the stone, now known as the Barber Stone (fifth image, below). The skeleton was lost for half a century, but it turned up in 1998, and examination revealed that the barber surgeon, if that was his profession, was NOT crushed by a falling megalith, but died a natural death and was simply buried beneath the Barber Stone.

Keiller found another stone that had been incorporated into a blacksmith’s forge in town. He recovered it and re-installed it, and it is now known as the Forge Stone (sixth image, below).

Keiller extracted many bronze-age and iron-age artifacts in his years of digging, and he set up a museum at Avebury to display his finds. The Alexander Keiller museum is still a going concern, although they have added a larger annex called the Barn Gallery as an additional display forum. As for Keiller himself, portraits are scarce. A small snapshot was the best Wikipedia could do, and I can do little better, with this photo of an older Keiller sitting down (seventh image, above). He would rather be remembered, I am sure, by the stones at Avebury. Few humans have a finer monument.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.