Scientist of the Day - Alexander von Humboldt

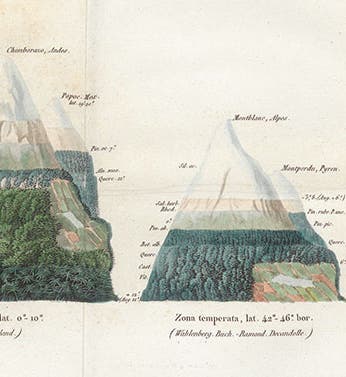

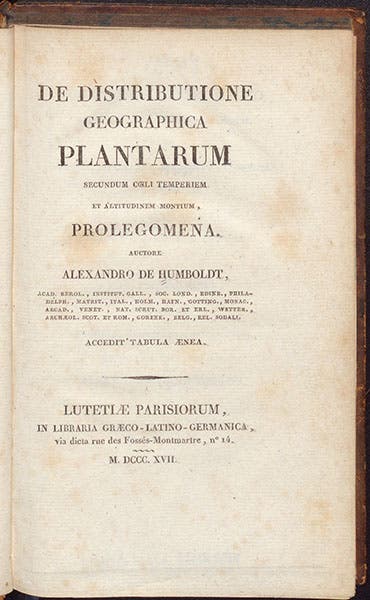

Vegetation pattern on two equatorial mountains (Chimborazo and Popocatépetl), two temperate mountains (Mont Blanc and Mont Perdu), and a “frigid” mountain (Sulitelma, Japan), detail of hand-colored engraved frontispiece, Alexander von Humboldt, De distributione geographica plantarum, 1817 (Linda Hall Library)

Alexander von Humboldt, a German explorer and naturalist, was born Sep. 14, 1769, in Berlin. We wrote our first post on Humboldt in 2015, where we discussed his five-year expedition (1799-1804) up the Orinoco River in South America with Aimé Bonpland, and the subsequent publication of his monumental 30-volume Le voyage aux régions equinoxiales du Nouveau Continent (1805-34), which we do not have in our library (we have a magnificent facsimile, but that is not quite the same thing). Humboldt influenced an entire century of naturalists with his emphasis on measurement and record keeping, not the least being Charles Darwin, who called Humboldt (and John Herschel) the two natural philosophers who influenced his life and career more than any others.

Humboldt inspired a variety of subsequent measurement programs, such as the "magnetic crusade" undertaken by British physicists (see our post on Edward Sabine), but he had perhaps his greatest impact on the new field of plant geography, which Humboldt in fact founded. Plant explorers before Humboldt created herbaria (collections of dried specimens) and brought home seeds and sprouts for botanical gardens in their native lands. Humboldt collected specimens too – thousands of them – but he also noted carefully the conditions of their existence: type of soil, annual rainfall, the quality of sunlight (by measuring the blueness of the sky), humidity, longitude, latitude, and altitude.

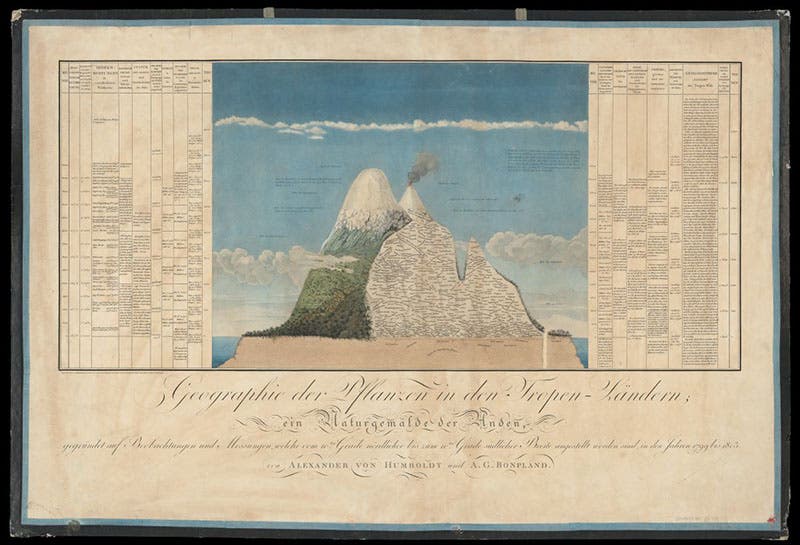

To present all this material in a comprehendible form, Humboldt invented a variety of novel graphics. His first one appeared in one of his first publications after his return to Paris, Ideen zu einer Geographie der Pflanzen (1807). The first edition is very scarce and we do not it in our collections. The large two-page hand-colored engraving that we show you is from a copy in the Zentralbibliothek in Zürich (third image).

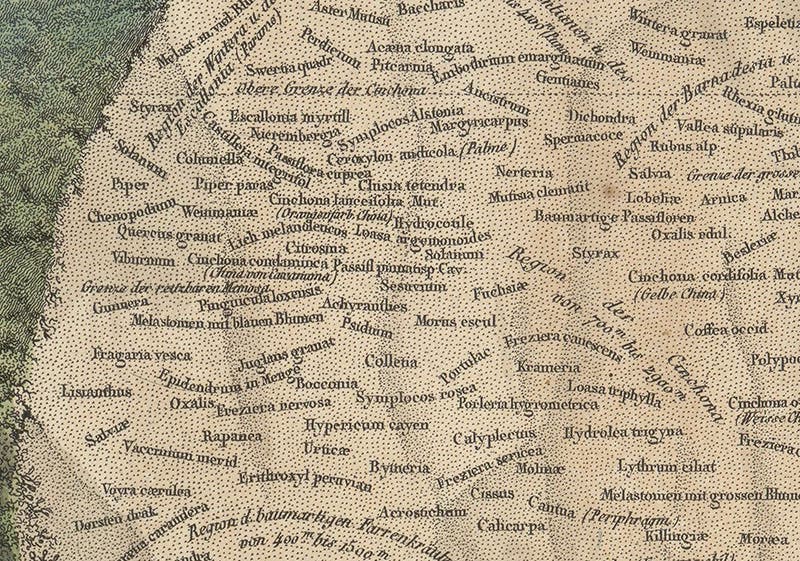

The central image shows the mountains of Chimborazo and Cotopaxi in the Andes. An artificial surface has been created on the right, almost like an irregular chalkboard, on which are written the names of plants – hundreds of plants. Their names are placed at a location that corresponds to the altitude at which they grow. Since you cannot see any of the names when you view the complete engraving, we have added a detail (fourth image).

The tabular material at left and right provides information about barometric pressure, temperature, strength of gravitation, breathability of the air, and a variety of other parameters. All together, they make up a tableau that is attractive yet rich in information.

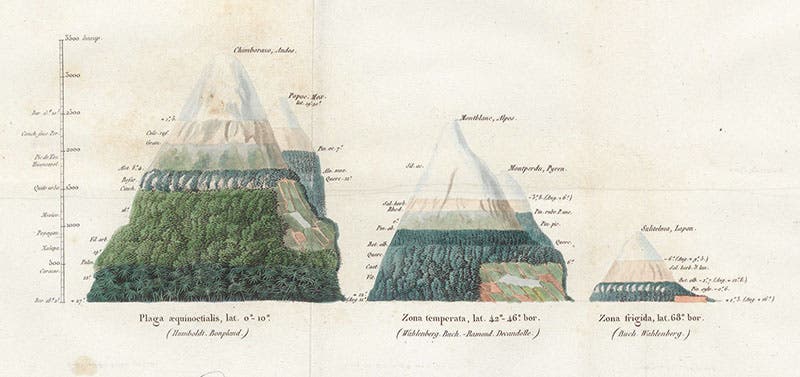

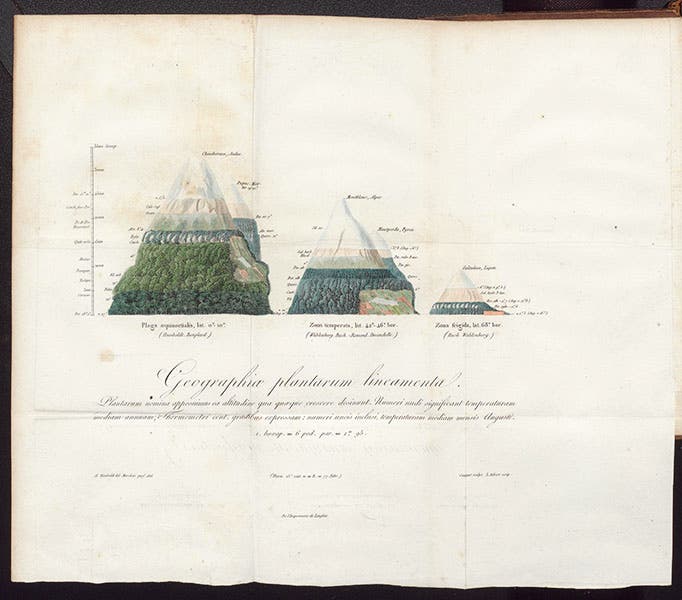

Ten years later, Humboldt published a book called De distributione geographica plantarum (1817; fifth image); this book we do have in our collections. The volume also has a folded, hand-colored engraving displaying the changing vegetation on mountains (sixth image; see first image for an enlarged view). It is cleaner than the first chart, as Humboldt has apparently realized that too many labels can muddy the waters. And another variable has been added for this chart – latitude. We see what appear to be three mountains, but are actually five, as two are tucked in behind. On the left is Chimborazo, with Popocatépetl of Mexico behind (see detail, seventh image); in the center is Mont Blanc, with Mont Perdu of the Pyrennes behind, and on the right is Sulitelma, in Japan. The mountains on the left are equatorial, those in the center are temperate, while the Japanese volcano is almost arctic. The point is that, just as vegetation changes as we go up a mountain, so does it change as we go north from the equator. A mountain is almost a microcosm of the Earth, with respect to plants. That was a novel idea in 1817. And it was an idea that lent itself well to a graphic presentation.

Vegetation pattern on an equatorial mountain (Chimborazo), a temperate mountain (Mont Blanc), and a “frigid” mountain (Sulitelma, Japan), entire hand-colored engraved frontispiece (see first image for an enlarged view), Alexander von Humboldt, De distributione geographica plantarum, 1817 (Linda Hall Library)

Humboldt’s charts proved immensely influential as thematic mapping became more and more popular in subsequent decades. Several years ago, we published a post on Heinrich Berghaus, who invented the thematic atlas in 1847, and one of the maps we included was very Humboldtian, showing changes in vegetation with both altitude and latitude. Humboldt was still alive at the time – indeed Berghaus was a friend – and he must have been pleased that his innovative graphics were changing the landscape of cartography.

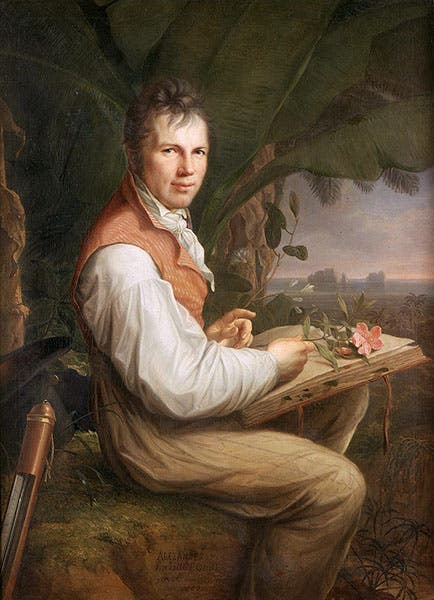

For some reason we failed to include a portrait of Humboldt in our first post, which was unfortunate, since there are many excellent portraits of the man, and they all deserve to be seen. Our portrait here, by George Weitsch, was painted in 1806, about the time that Humboldt published his first graphic. The portrait is in the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.