Scientist of the Day - Alexander von Middendorff

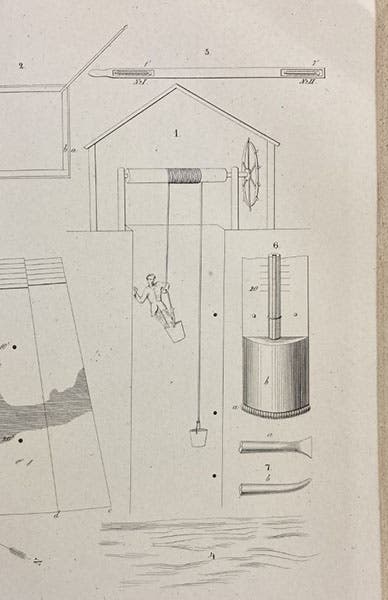

Alexander Theodor von Middendorff, a Baltic zoologist and explorer working in Russia, died Jan. 28, 1894, at age 68. In 1841, Middendorff, although still a young and unproven zoologist teaching in Kiev, was selected by Karl von Baer to lead an expedition across Siberia to investigate permafrost, which was a great mystery at the time, and in fact a phenomenon in which many did not believe. The only experience Middendorff had in Arctic exploration was a trip he took with Baer in 1840, intended for Novaya Zemlya, the large island in the Arctic Sea that looks like a right eyebrow, and which the expedition failed to reach, exploring Lapland and the White Sea instead. Baer saw something in young Middendorff, and he persuaded the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences to choose him to lead an expedition eastward across the 5300-mile Siberian highway, with one long trip up to the Arctic Ocean to the Taymyr Peninsula, and another to Yakutsk, far eastward, in the middle of nowhere on the Lena River, not far from the Sea of Okhotsk. Yakutsk was chosen because an earlier investigator had tried to drill a well there, and had found the ground frozen solid, and went down 350 feet before the ground began to soften. It seemed the perfect place to measure the effects of permafrost, and demonstrate its reality, and its properties.

Modern map of Russia, with the trans-Siberian highway running across the bottom from St. Petersburg and Moscow to the Sea of Okhotsk. The Taymyr Peninsula explored by Middendorff is at top center, jutting into the Arctic Ocean. The Sea of Okhotsk is a 5300-mile trek by cart or carriage from Moscow (worldometers.info).

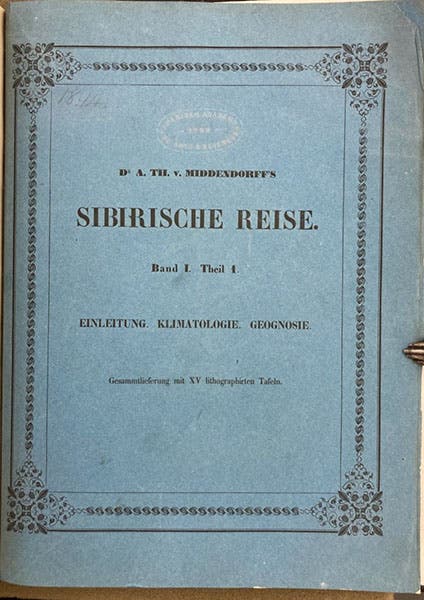

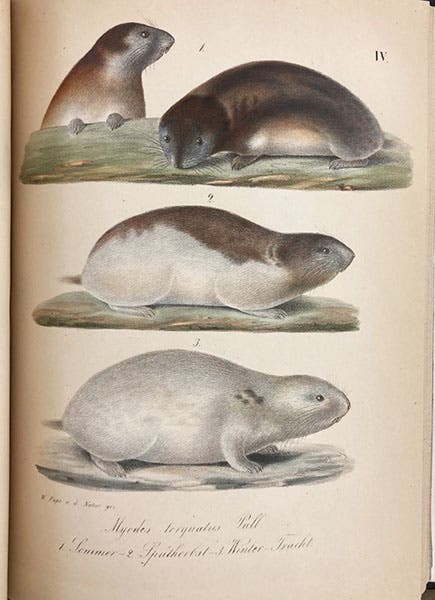

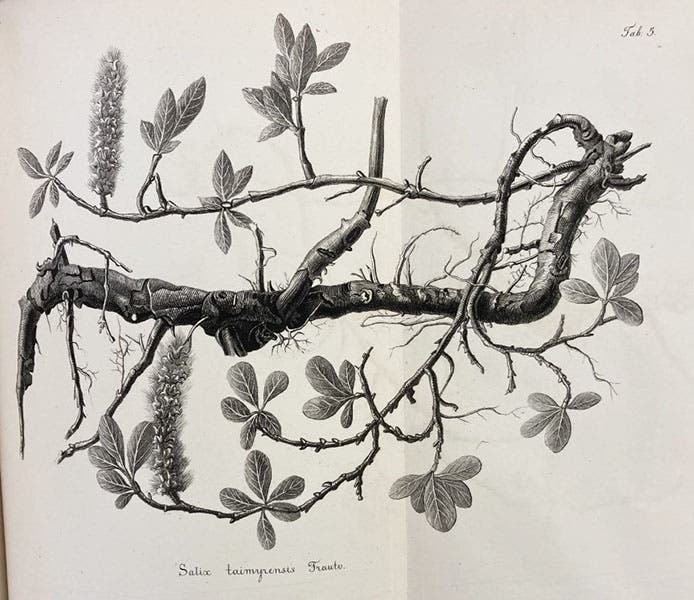

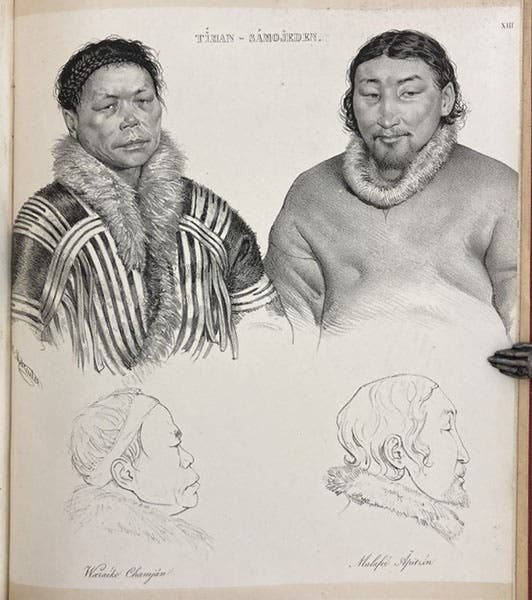

Middendorff's expedition lasted for two years, 1843-45. He made it to Krasnoyarsk, 2600 miles from Moscow on the Siberian highway, and then up the Yenisey River to the Taymyr Peninsula, mapping the entire area. He almost did not come back, as on one occasion, he was left alone at 75° north latitude without a tent for 18 days while his companions went looking for help from the native Nenets. But he survived, and the next year the expedition made it to Yakutsk, to undertake the geothermal investigations. In addition to the permafrost studies requested by Baer, Middendorff, being a zoologist, studied the flora and fauna of the places he visited, and the geology as well. They also visited some islands in thE Sea of Okhotsk, and the Amur River in China. After his return, Middendorff spent the next twenty years of his life writing up the results of the expedition. Reise in den äussersten Norden und Osten Sibiriens während der Jahre 1843 und 1844 was published in four fat quarto volumes (actually 5, since one volume has two parts, each bound separately) from 1847 to 1867. We have these 5 volumes in our collections, although we lack the atlas of maps that was published in 1859 to accompany the text. But the volumes we do have contain scores of plates, from which we have selected several to illustrate this account.

Middendorff is hardly ever included in discussions of the great Arctic explorers, where you will find mention of Edward William Parry, John Franklin, and Roald Amundsen, but he should be in their company, as he journeyed farther than any of them, in extremely difficult conditions, and none of that by ship.

Diagram of the top of the 350-foot well drilled into the permafrost in Yakutsk, where Middendorff’s assistant used an array of thermometers to measure the temperature down the depth of the well, detail of engraving in Reise in den äussersten Norden und Osten Sibiriens während der Jahre 1843 und 1844, by Alexander von Middendorff, vol. 1, pt. 1, plate 12, 1867 (Linda Hall Library)

Background to Middendorff’s expedition was provided by an excellent article, “Alexander von Middendorff and his expedition to Siberia, 1842-1845,” by Erki Tammiksaar and Ian R. Stone, Polar Record, 2007, vol. 43, pp. 193-216, which also was the source for the portrait (first image). The article includes several examples of Middendorff’s maps from the expedition Atlas (1859), which unfortunately was never included with our five volumes of narrative.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.