Scientist of the Day - Alexine Tinné

Alexine Tinné, a Dutch heiress and explorer, was born Oct. 17, 1835. Her father died when she was young, leaving her mother, the Baroness Henriette, one of the wealthiest women in the Netherlands. Mother and daughter travelled extensively about Europe when Alexine was in her mid-teens, which would not have been noteworthy, except they travelled without the company of men, which was highly unusual. Alexine sat for a portrait when she was just 14 years old (first image).

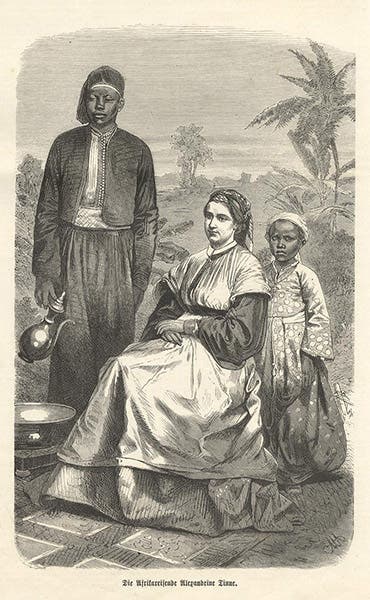

Then, in 1854, the two set off for Cairo, apparently to mend a broken heart suffered by Alexine. They spent several years making "safe" trips, taking pleasure cruises up the Nile, and joining a camel caravan crossing the desert from Luxor to the Red sea. Then they began to venture further south (further "up" the Nile), hoping to make it into Sudan, where the search for the source of the Nile, undertaken by British (and male) was beginning to take shape. Thwarted by the cataracts at Aswan on their first attempt, they returned for a year to The Hague to prepare for and outfit a larger expedition. They also took the time to sit for a group portrait (second image; Alexine is at left, Henriette in the center, a cousin at the right).

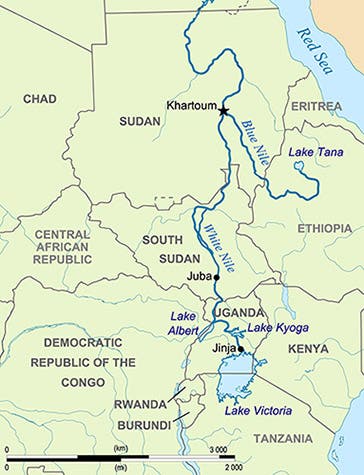

This venture got underway in 1862 and employed three large Nile River boats, which carried, in addition to what were now three Dutch ladies (the sister of the Baroness had joined them), four Dutch servants, a cook, five dogs, a number of pack animals, grooms, a hunter, 3 iron beds, provisions for a year, and, in the last boat, 32 trunks containing the necessities of life appropriate for the social elite of Europe. All of this had to be portaged around the cataracts, but they did eventually make it to Khartoum, where the Blue Nile and the White Nile come together. Alexine decided to rent a steamer – the only steamboat in Khartoum – and proceed up the White Nile into dangerous and poorly explored South Sudan, into the area called Bahr-el-Ghazal (see map). It was at this point that Alexine began to morph from a rich tourist into a scientific explorer. She hired two German scientists in Khartoum, an ornithologist and a botanist, and both, as it turned out, were also excellent artists and cartographers. They collected plants and made surveys and maps, and the plants, which made it back to Germany, were the basis for a book on the botany of Bahr-el-Ghazal, titled Plantae Tinneanae (1869). Geographic reports were also read to the Royal Geographical Society in London, where president Roderick Murchison was mightily impressed with the pluckiness of "the Dutch ladies." We see here a wood engraving of an older and wiser Alexine, probably based on a photograph taken in the Sudan (fourth image).

Otherwise, the Bahr-el-Ghazal expedition was pretty much of a disaster. The steamer could only take them so far, and they had trouble with the porters, and fevers, so they eventually had to return to Khartoum, where the Baroness died, as did her sister, and Alexine's Dutch servants, who had been with her since she was a child. Alexine stayed on in Egypt, although she had lost her appetite for river exploration; she lived for a while in Cairo, and then on board a Mediterranean yacht, but in 1869, she decided to become the first woman to cross the Sahara, setting out with Tuareg camel drivers from Algiers. She was murdered by the Tuaregs somewhere in southern Libya. She was 33 years old.

Alexine may not have accomplished much as a scientist; indeed, she was probably not a scientist at all, just an intelligent and savvy woman who realized that having scientific aspirations, and hiring scientific experts, can legitimize an expedition, and it certainly did legitimize hers. After her death, she became the subject for countless articles and stories in popular magazines, the epitome of the courageous heroine, the woman who dared to be different. At a time when it was considered shocking and scandalous for a woman to head off on her own into unexplored territory, she claimed the right to pursue goals that heretofore had been deemed exclusively male. For that, she deserves our admiration.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.