Scientist of the Day - Alexis Bouvard

Alexis Bouvard, a French astronomer and mathematician, died June 7, 1843, at the age of 75, having been born on June 27, 1767, to a peasant family in Contamines-Montjo, in the French Alps. How he managed to rise from such lowly beginnings, I have no idea, but when the French National Convention founded the Bureau of Longitude in 1795, with authority over the Paris Observatory, there was Bouvard, who had somehow come to the attention of Pierre-Simon Laplace and some of the 10 other board members and soon became their secretary. Bouvard was very good at calculating planetary positions, which many astronomers regarded as drudge work (which it was), and it was probably this ability that drew the attention of Laplace, who had Bouvard do much of the calculations for his great work on celestial mechanics, the Traité de Mécanique Céleste, (1798-1825).

Using those skills, Bouvard spent many years preparing his own book on planetary positions, with the full title: Tables astronomiques publiées par le Bureau des longitudes de France, contenant les tables de Jupiter, de Saturne et d'Uranus, construites d'apres la theorie de la méchanique celeste (1821), which transliterates well enough into English. Note that Bouvard dedicated his book to his hero Laplace (third image), the man who 20 years earlier had been fired by Napoleon just six weeks into his tenure as Minister of the Interior, as we mentioned in our post a few days ago on Jean-Antoine Chaptal.

The Tables astronomiques recorded past positions and predicted future ones for the three outer planets, Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. Jupiter and Saturn presented little problem, as they had been observed and tracked for 2500 years. Uranus was a bit different.

Uranus had been discovered, quite unexpectedly, by William Herschel, on Mar. 13, 1781. He just looked through his telescope (which he made himself) and there it was, and continued to be. Other astronomers began to track it immediately, so a body of observed positions accrued, but it was limited to the 1780s, and then the 1790s, which was a short time for a planet whose orbit around the Sun takes 84 years. Astronomers decided to see if anyone in the past had observed it, but had not realized that it was a planet, and sure enough, they found quite a few earlier observations, by astronomers such as Pierre-Charles Le Monnier, who recorded Uranus as a star a dozen times. They even found that John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal of England, had recorded it twice, in 1690, without realizing that it was a planet, not a star. So that gave the planetary calculators almost a full circuit’s worth of observations, from which they could reconstruct the orbit of Uranus. And astronomers like Bouvard proceeded to do just that.

The problem with the early orbits for Uranus was that, over time, they grew increasingly inaccurate. Predicted positions made from the early models were off, increasingly so, as the years went by, as you can see from a table that Bouvard included at the beginning of his section on Uranus, where the error in longitude for 1819 was 76 arcseconds, an enormous discrepancy (fourth image). Bouvard got the bright idea (probably from Laplace) that perhaps the two large planets, Jupiter and Saturn, were "perturbing" the orbit of Uranus, that is, tugging on it with their large masses and causing it to deviate from its predicted path. This was the first time anyone had considered that the gravitational pull of the large planets has to be taken into acount, which made for very long and messy equations. So Bouvard was able, in his 1821 book, to come up with a series of annual predictions of the observed longitude of Uranus, and for its distance from the Sun (its radius vector, as it is called). We show you the second page of his tables, with predicted longitudes from 1810 to 1854 (fifth image).

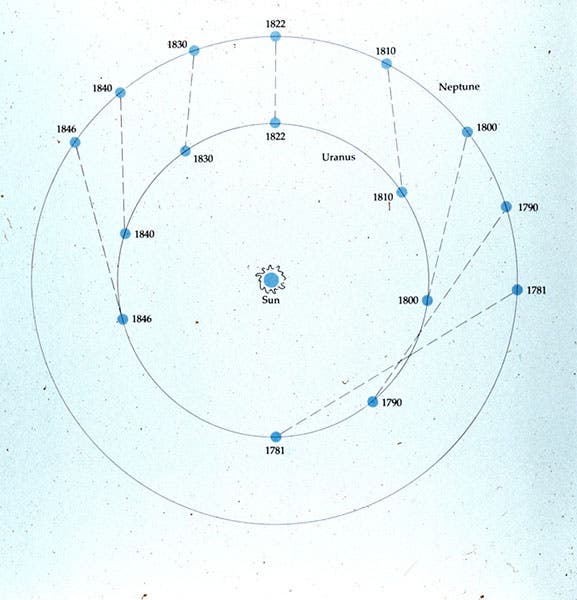

Modern diagram of the orbits of Uranus (inner circle) and Neptune (outer circle) from 1781, when Uranus was discovered, to 1846, when Neptune was found; both planets move counterclockwise. Note that Neptune pulled on Uranus and speeded it up until 1822, and then it pulled to slow it down until 1846 and beyond; unknown source (author’s image collection)

But even before his book was published, in 1821, the predicted positions were off, and they got worse. Bouvard himself realized that perhaps the problem was caused by an eighth and undiscovered planet, out beyond Uranus, that was pulling on its neighbor, speeding it up, then slowing it down. And this turned out to be the case. As we see in a modern diagram (sixth image), Neptune was tugging on Uranus from 1781 to 1822 and speeding it up, and then from 1822 to 1846 and beyond, was pulling to slow it down. Although no one in the 1830s believed that the hypothesis of an 8th planet was any help, since it was thought impossible to predict where it might be, two astronomers in the 1840s, Urbain Le Verrier of France and John Couch Adams of England, were able to solve their six equations in six unknowns and predict the position of an eighth planet, which was discovered in 1846, right where Le Verrier said it was, and close to where Adams had predicted it should be. The discovery of Neptune was the greatest achievement of predictive astronomy ever, and Bouvard, by demonstrating that the perturbations of Jupiter and Saturn were not enough to explain the path of Uranus, in a sense made it all possible. We have not yet written a post on Adams, but there is a great deal about his role in the Neptune controversy in our post on George Biddell Airy.

Bouvard, immediately after his Tables for Uranus was published, in 1822, became Director of the Paris Observatory, continuing in a long line that began with Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1669. Bouvard died in 1843, just three years before Neptune was discovered by Johann Galle in Berlin, acting on the predictions of Le Verrier. For a memorial for Bouvard, one must make do with a simple wooden plaque on the farm where he was born (seventh image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.