Scientist of the Day - Alfred Beach

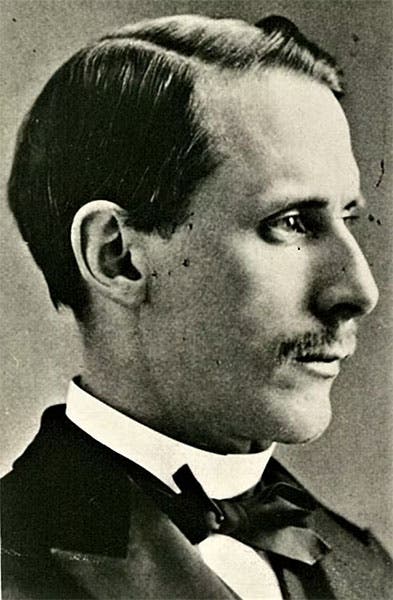

Alfred Ely Beach, an American inventor, publisher, and patent lawyer, was born Sep. 1, 1826, in Springfield, Mass. The son of a publisher, Alfred and a friend, Orson Munn, bought the magazine Scientific American in 1846, less than a year after it had been founded by Rufus Porter. They published the magazine until their deaths (Beach's came in 1896), and it was subsequently published by their sons and grandsons.

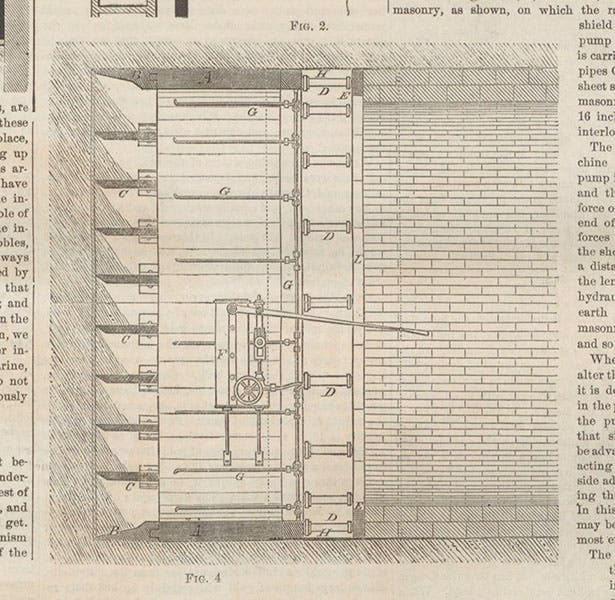

Beach is best known for an invention, a round tunneling shield. The tunneling shield, as an idea, was about 50 years old when Beach introduced his. A tunneling shield is a device to facilitate the building of underground tunnels, usually for railways, and, a the name suggest, to protect the workers from cave-ins. If you want a square tunnel, the shield will have a strong and rigid square frame. One end, usually with separate compartments, is placed against the surface to be dug out. The other end, open to the completed part of the tunnel, is designed to enable the insertion of iron supports and/or bricks to complete the tunnel. As the digging progresses, powerful screws allow the shield to be advanced forward, and the newly exposed roof and sides can be tiled or bricked.

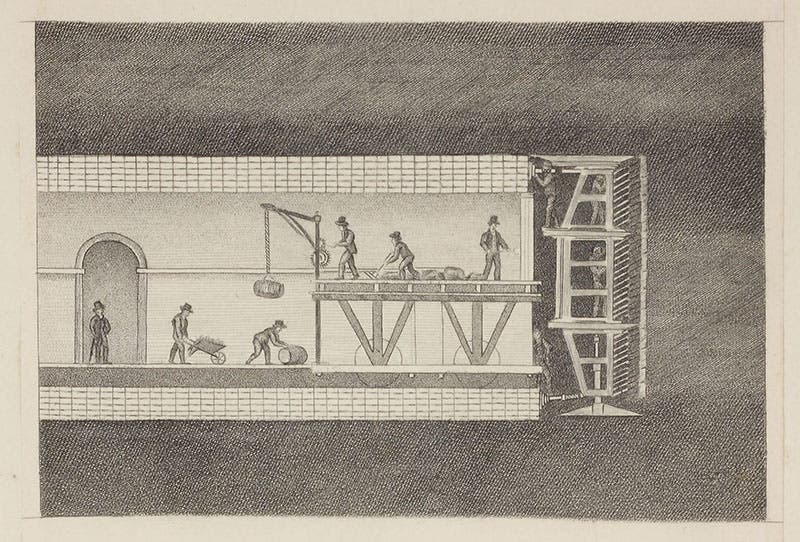

Shields were first used for the digging of the Thames tunnel, beginning in 1825; the Thames tunnel shield was designed by Marc Isambard Brunel. It was rectangular, and simply provided a place for diggers to stand, protected from cave-ins, and also provided a platform for the bricklayers who reinforced the walls and ceiling. But even this first one had jackscrews to inch the shield forward as the diggers dug, perhaps the key idea for a successful and useable shield. We have quite a few books on the building of the Thames Tunnel in our collections; we include here an image from one of them, published in 1836, that shows Brunel’s shield at work (third image).

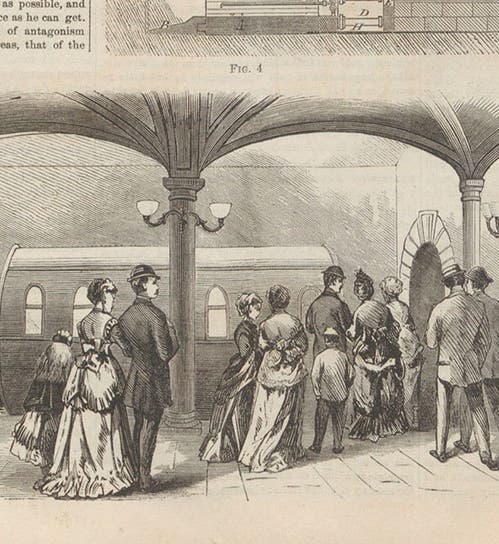

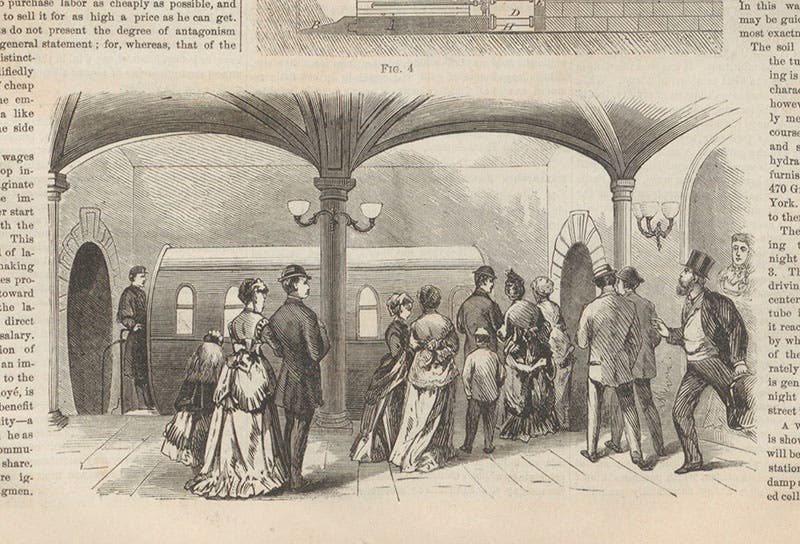

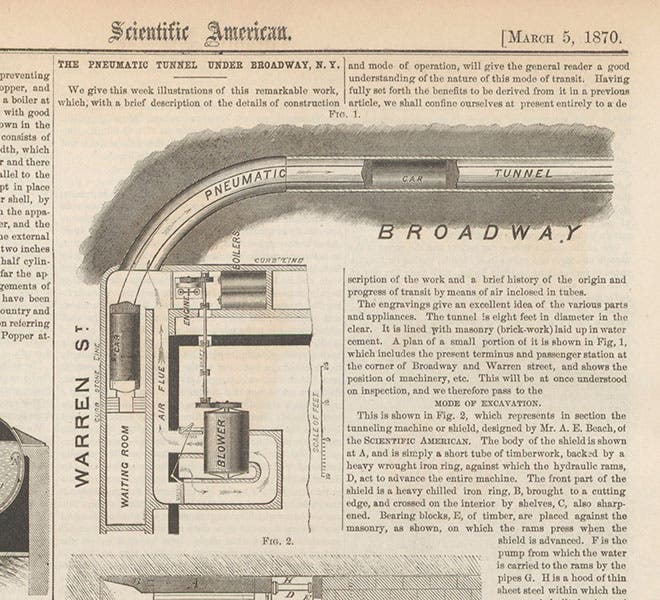

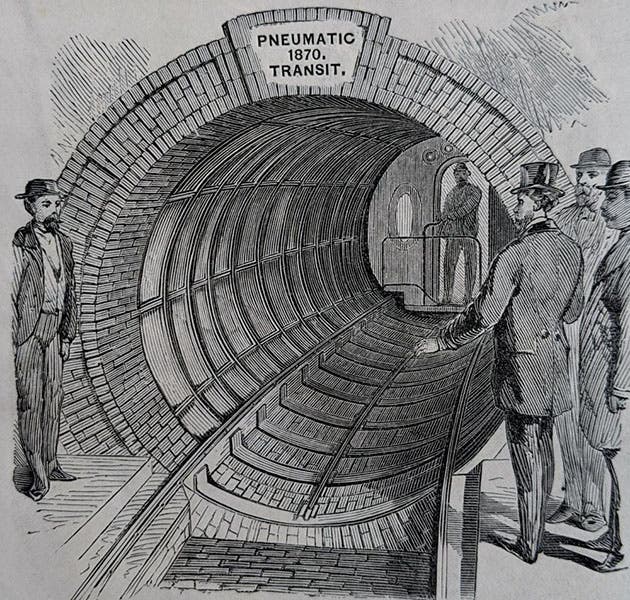

No other tunnelling shields were built or used until the 1860s. Beach seems to have come up with the idea for a New York underground railway in the late 1840s, but with no easy way to build it, until sometime before 1870, by which time he had built his own tunneling shield. The Beach device was circular rather than square or rectangular, the idea being that a tunnel with a circular cross-section would be stronger and easier to line with iron or bricks. He proposed to use his shield to dig a tunnel under Broadway, and he got permits to build a test section of tunnel and track, which he completed in February of 1870. Not surprisingly, Scientific American ran a full-page story on the Broadway Underground Railway Tunnel on Mar 5, 1870, with good illustrations of shield, tunnel, and station, three of which we show here.

One of Beach's innovations was to use hydraulic rams instead of jackscrews to advance the shield, all of which could be operated by one man and one hydraulic handpump. Also, there were no human diggers, as the round front edge of the shield was sharpened, and there were additional cutters that ran across the face that could be pushed right into the soft earth that underlay Broadway. All the humans had to do was carry the dirt away in barrows.

Beach's other novel idea was to use air pressure to move the car through the tunnel. Small pneumatic tube systems were all the rage at the time (we still have an operational one here in the library), which probably gave Beach the idea. He used a steam engine to power a large blower that literally blew the passengers to their destination.

Beach's pneumatic railway included an underground station on Warren Street (first image), then the tunnel curved right to go down Broadway to Murray Street, one whole block away (fourth image). The pneumatic subway worked beautifully, and for a few years, it was the most popular ride in town, as, in the first year alone, 400,000 people paid 25 cents each to ride 300 feet down the tunnel and back again. Whether it would work on a larger scale we will never know, as Beach's repeated attempts at getting permits for a longer line were rejected by Tammany Hall and other powerful lobbies, and then a stock-market crash scared all the investors away. Neither Beach's subway nor any others would be constructed in New York City until the end of the century.

Interestingly, while Beach was designing his shield and building his tunnel, James Henry Greathead in England invented his own circular tunnelling shield and used it to dig a subway tunnel under the Thames, also opened in 1870. Greathead would later build a second and larger subway under the same river, in 1886. For the 1870 tunnel, the car was pulled through the tunnel by a cable. The second subway was powered by an electric locomotive. Neither was a great success. You can read about it in our post on Greathead.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.