Scientist of the Day - Alfred Charles Hobbs

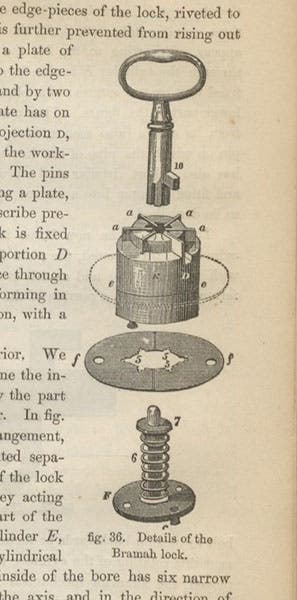

Alfred Charles Hobbs, an American locksmith, was born in Boston on Oct. 7, 1812. In 1851, he went to London to represent his lock firm, Day & Newell of New York, at the great Crystal Palace Exhibition. At the time, the English made the best locks in the world. Joseph Bramah (with the help of Henry Maudslay) had made a padlock in 1790 that he claimed was unbreakable, and he displayed in in his shop window along with a sign, offering 200 guineas to the person who could open it without a key. It came to be known as the Bramah challenge lock. The lock and the sign remained there for 61 years, as Bramah's sons took over the business, with no successful challengers.

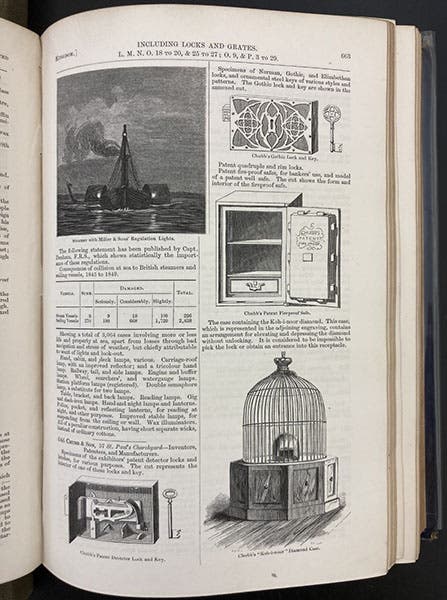

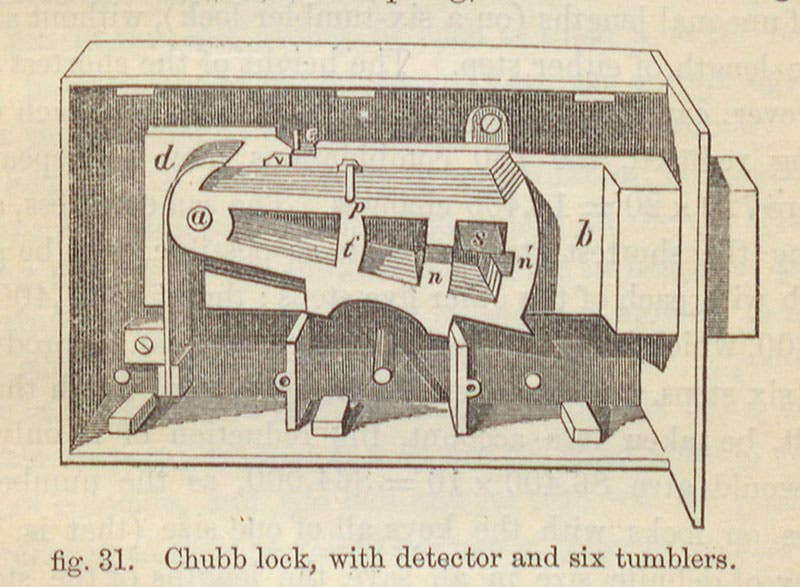

In 1818, another London lock-maker, Jeremiah Chubb, invented what he called a detector lock. This was a bolt lock, so designed that if it were tampered with, the tampering was detected by the mechanism, the lock froze up, and the owner was alerted that someone had tried to pick the lock. The Chubb firm had a booth at the Exhibition, where the detector lock was on display, as we can see from a page in the exhibition catalog (third image). The case at bottom right was designed by Chubb to exhibit the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond. A detail of the detector lock mechanism, from a different source, is just below that (fourth image).

Once he had his firm's exhibit set up, Hobbs accepted the challenge of the Bramah firm; he wanted to try to pick their lock, and they had no choice but to allow him. Conditions were established, whereby Hobbs had to work on the premises, but could bring with him whatever tools he wanted, with the proviso that the lock had to remain undamaged and workable, even if picked. And Hobbs did it. It took him 51 hours and 16 days, and all sorts of tiny, specially designed instruments, but eventually he opened the lock. The oversight committee was not happy, since Hobbs' specialized approach was hardly one available to a burglar, but they paid the 200 gold coins, which had been on display at the Exhibition. Hobbes left the coins right there for the duration of the fair, as advertisement that a London lock firm had been bested by a New York establishment. And then Hobbs proceeded to pick the Chubb detector lock. It was quite a coup for the Americans.

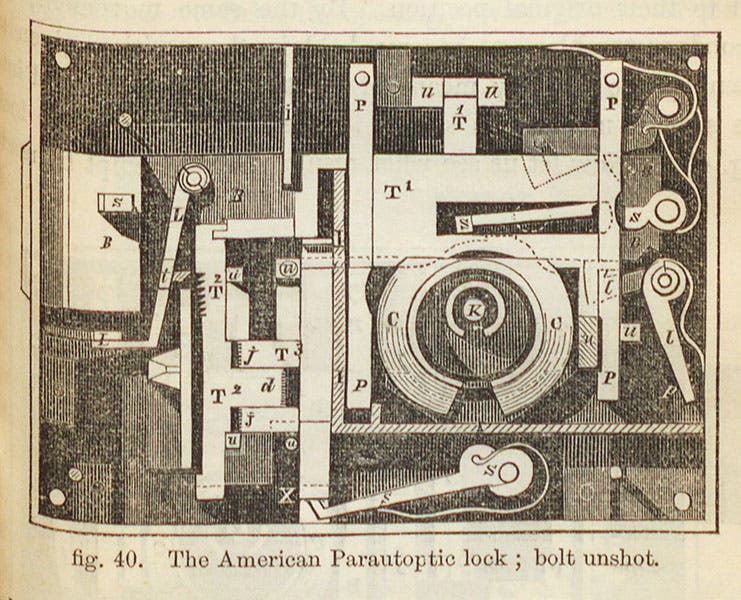

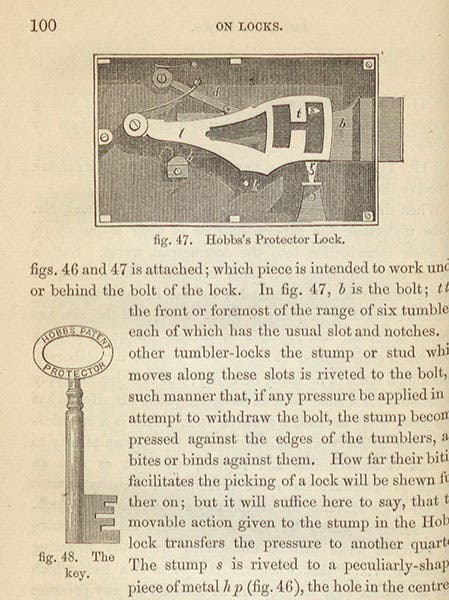

It is sometimes said that the London lock-making industry was crushed by Hobbs' achievements, but that was hardly the case. Any lock that can withstand attempts to open it for 51 hours is a fairly impregnable lock, and both Bramah and Chubb lock sales were unaffected. If anything, they were bolstered by the events at the Exhibition. Hobbs' firm of Newell & Day did not fare so well. The lock they exhibited in London, the parautoptic lock (sixth image), was picked right after the fair, by the American locksmith Linus Yale (who would go on to establish his own now famous lock firm), and Newell & Day went out of business. It has recently been suggested that Hobbs might have revealed the secrets of the parautoptic lock to Yale, as part of a deal – Yale would not patent his locks in England, leaving the field open for Hobbs and his new “protector" lock (seventh image). I don't think there is any direct evidence of such conniving, but the fact is, Yale did not attempt to enter the English market, and Hobbs did set up a lock-making firm in London that was quite successful.

Lock-makers did not publish books revealing the secrets of their locks, so we have no publications by Hobbs, Bramah, or Chubb in our collections. However, we do have a book by Charles Tomlinson, Rudimentary Treatise on the Construction of Locks (1853), which has small wood-engraved diagrams of the Bramah challenge, Chubb detector, Newell & Day parautoptic, and Hobbs protector locks, several of which we have used to illustrate this post. The diagrams, however, do not really tell you how the locks work, which was probably intentional.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.