Scientist of the Day - Alfred Nobel

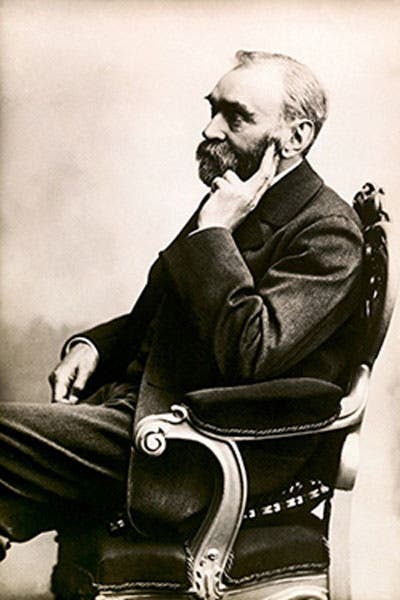

Alfred Bernhard Nobel, a Swedish chemist and industrialist, was born Oct. 21, 1833, in Stockholm, Sweden. His father was a sometimes-successful inventor and manufacturer of munitions, and during his successful period, the family moved to St. Petersburg, where the father sold arms to the Russian army and where Alfred was educated, acquiring his lifelong interests in not only chemistry, but literature and the arts. When his father's business faltered, some of the family, including Alfred, moved back to Stockholm, where they set up a munitions factory.

By the time he was 20, Nobel had become interested in making a usable mining explosive, something better than black powder. Nitroglycerin, a very powerful explosive, had been invented by Ascanio Sobrero in Turin in 1847, but it proved to be a very volatile and unstable compound, so dangerous that its inventor disowned it. Nobel learned about nitroglycerin in 1850. For it to be of any practical use, nitroglycerin had to be stabilized, and that is what Nobel worked toward, as he moved from Stockholm to Paris to Germany to Italy, setting up laboratories and factories and becoming quite successful, all the while working on the nitroglycerin problem.

A disastrous explosion in Stockholm in 1864, which killed his younger brother, forced the firm to move out of the city. Shortly thereafter, Nobel discovered that if nitroglycerin were mixed with a quantity of what the Germans called Kieselguhr, and we would call diatomaceous earth, then the nitroglycerin became workable and much less likely to explode if jarred or dropped; it had to be detonated by a blasting cap, which Nobel also invented. He received a patent for his new explosive in 1867; he called it Dynamite. It was marketed in sticks, which were just perfect for placing in boreholes drilled in mines (fourth image). Nobel’s Dynamite was soon being used around the world, supplied by Nobel plants in Hamburg, Sweden, Sevran (France) and Sanremo (Italy).

Nobel later invented another kind of mining explosive, called gelignite, and a substitute for gunpower, that he called ballistite, which had the advantage over black powder of being completely smokeless. All were successful products and made Nobel a very rich man.

Although he always retained close ties to Sweden, Nobel lived in Paris from 1874 to 1891. When he invented ballistite and tried to sell the rights to the French government, they were not interested, claiming they already had a good explosive powder for their military. So Nobel sold the license to Italy, which promptly and enthusiastically began to manufacture it for their armed forces. When ballistite proved to be a superior explosive, the French government turned on Nobel and castigated him as a traitor, supplying arms to foreign governments. He was forced to move to Italy, where he spent the last four years of his life, in Sanremo.

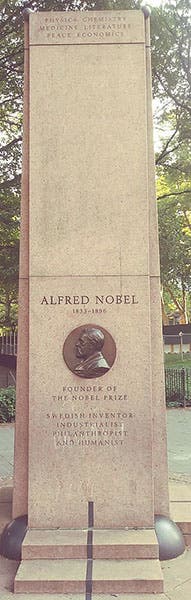

The story goes that when Nobel's older brother died, the French press thought it was Alfred who had passed away, and an obituary viciously proclaimed Alfred to have been a merchant of death. Still very much alive, and alarmed by the thought of leaving such a legacy, Nobel decided to improve his posthumous reputation by leaving the bulk of his estate to fund five prizes, to be awarded annually to those who had made important contribution to physics, chemistry, medicine or physiology, literature, and the promotion of world peace. He stipulated that the Nobel Foundation would manage the assets and the Royal Academy of Sciences in Stockholm would select the prize recipients. Nobel died shortly after the will was made, in 1895, and although the heirs were not happy and fought the terms of the will in court, his wishes prevailed, and the first Nobel Prizes were awarded in 1901 (the inaugural prize in physics went to Wilhelm Röntgen, discoverer of X-rays). And if Nobel was motivated by the fear of being remembered only as a warmonger, his strategy certainly worked. He is often regarded today not only as an important inventor and philanthropist, but as one of the great figures in the history of science, which is probably overstating the case considerably. Still, every place he ever lived now claims him as their own, and there are Nobel museums in Björkborn, Sanremo, Sevran, and probably in Hamburg as well (fifth and sixth images). He even has an element named after him, nobelium, which was probably taking the honorifics a bit too far. I am not sure nobelium belongs in the same transuranic universe as einsteinium, curium, and fermium.