Scientist of the Day - Alphonse de Neuville

Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville, a French painter and illustrator, died May 18, 1885, at the age of 50. Many of de Neuville's paintings are well known, but they primarily depict military subjects – battles, sieges, and the life – which would never gain him admittance to the ranks of Scientists of the Day. Fortunately, when he was young and not yet established, he did a certain amount of book illustration. Jules Verne's Vingt mille lieues sous le mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea) was having a successful run in the serial, Magasin d'éducation et de récréation, published by Pierre-Jules Hetzel. The series run started in 1869, and was unillustrated; Hetzel realized very quickly that it would be a best-seller in book form, especially with illustrations, and he commissioned de Neuvillle, Edouard Riou, and possibly a third artist to supply the pictures. The book was published in 1871, with nearly 120 wood engravings.

We do not have Verne's book in our collections, so I had to page through an online copy of the first edition of 1871, provided by the Bibliotheque nationale in Paris, to find the wood-engravings signed "AdN". The first dozen or so illustrations are signed "Riou," then de Neuville takes over as the primary illustrator. However, there are quite a few engravings not signed at all, so either there was a third (and shy) illustrator at work, or de Neuville or Riou failed to sign some of their handiwork. It is hard (for me) to tell the two apart stylistically, so I didn't attempt to assign authorship to any unsigned illustrations. All of the images shown here are signed "AdN." And we might mention that every wood engraving also has the signature "Hildibrand" – he was the wood engraver for all the prints, but not the artist for any.

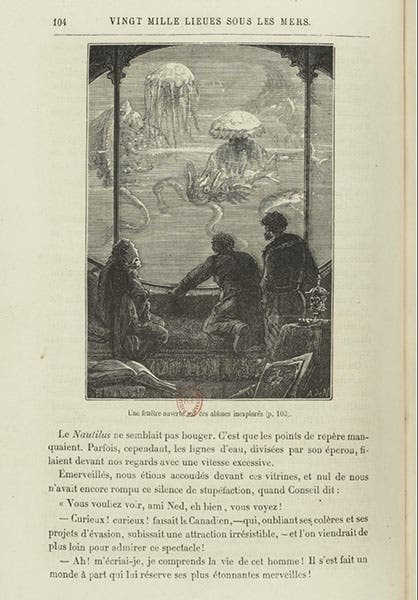

I chose five of the more dramatic images contributed by de Neuville, and in describing them I will try not to spoil the story for those of you who have not read Verne's book. First, we show the moment when the shutters in the salon of the Nautilus are first opened to expose Professor Arronnax and his two companions (prisoners on the Nautilus) to the glory of the undersea world (third image, above).

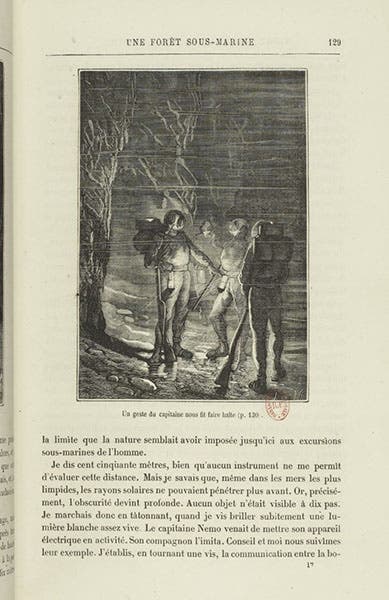

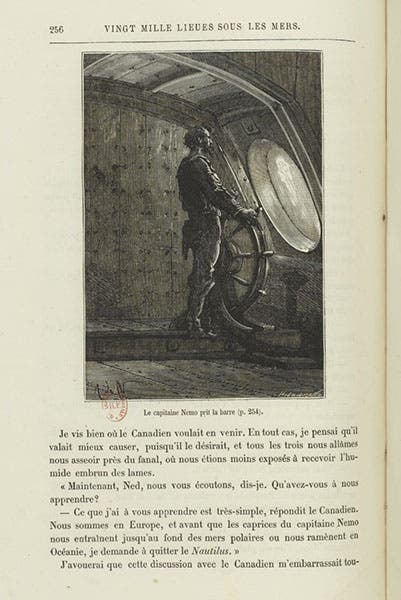

A moment when Captain Nemo and Professor Aronnax are in their deep-sea walking suits on the ocean floor is captured in another de Neuville illustration (fourth image, above). For some of these images, we show just the wood-engraving and its caption; for others, we present the entire page, so you can get a better feel for how these would look if you were actually reading a first edition.

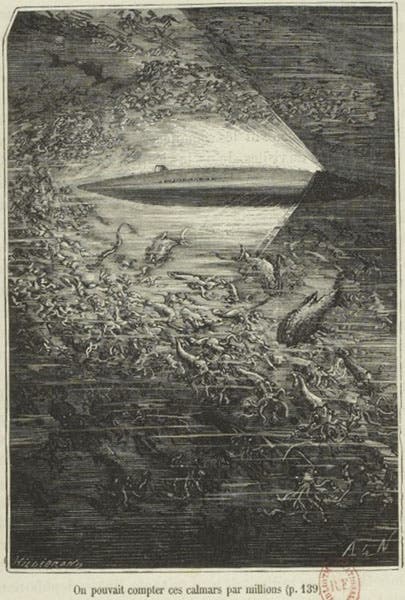

Our fifth image (above) shows the Nautilus, with its electric torch cutting quite a swath, coursing through “millions” of calamari. And the sixth image (below) depicts Captain Nemo at the wheel of the Nautilus.

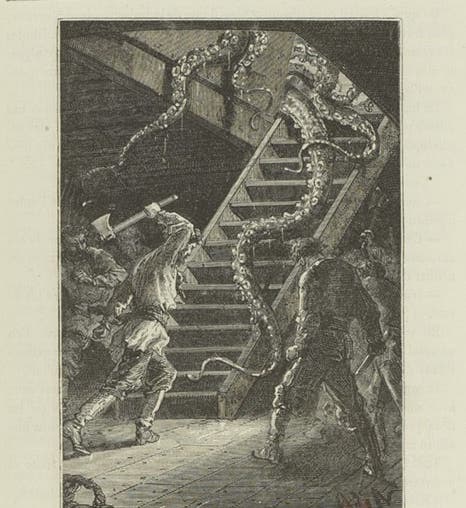

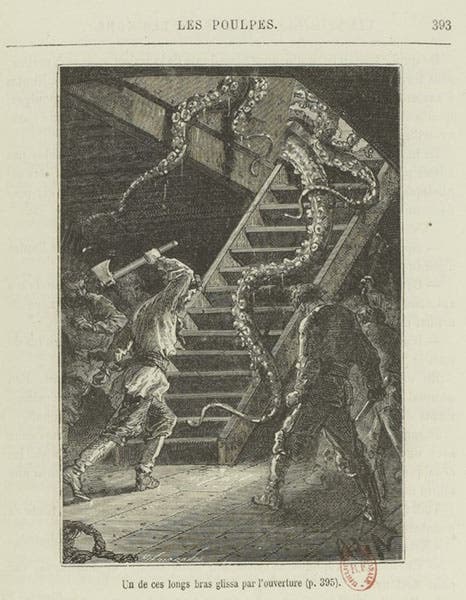

Our last image we placed first, since it is the most dramatic, showing the tentacles of the giant squid making their way down the hatches of the Nautilus. There are a number of illustrations in the 1871 edition of the Nautilus-squid encounter, but most of them are unsigned. This one was definitely de Neuville’s handiwork.

The illustrations provided by Edouard Riou for Verne’s book are just as gripping as those of de Neuville. We wrote one post on Riou six years ago, but we there discussed his contributions to Louis Figuier’s books on prehistoric life and primitive humans and did not discuss his work for Jules Verne. Perhaps we will one day write another post to show Riou’s contributions to Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. Until then, here is a link to the full-page frontispiece of the book, drawn by Riou. And finally, we need to write something on Jules Verne himself. We do not have any of his books in he Library, which is why I have held off writing about him, but Verne had a massive influence on the public perception of science in the last 35 years of the nineteenth century, and he really deserves an entry, if not two or three. Perhaps next Feb. 8, his birthday, would be a good time to give Verne his due.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.