Scientist of the Day - Alphonse Milne-Edwards

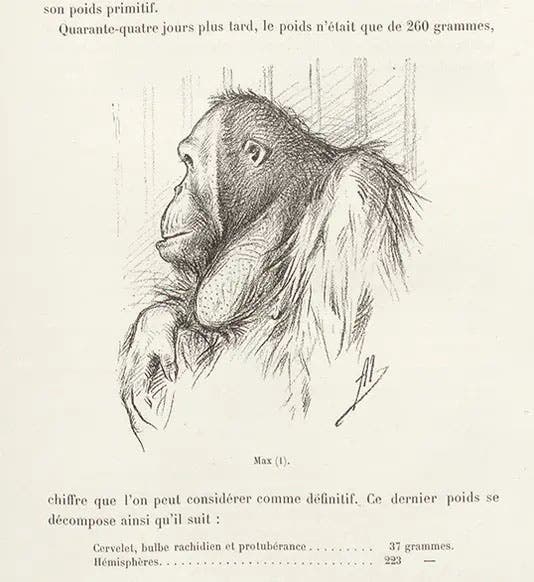

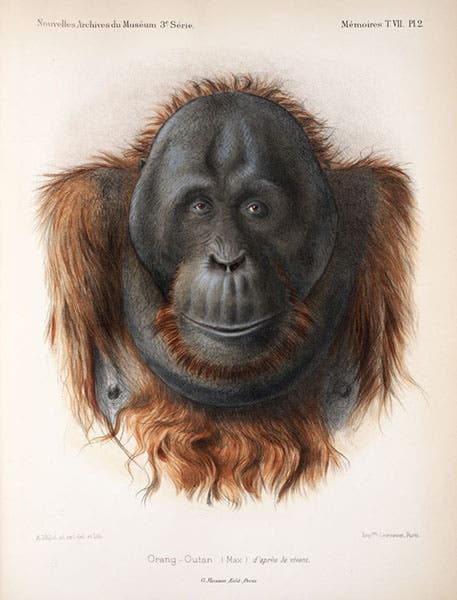

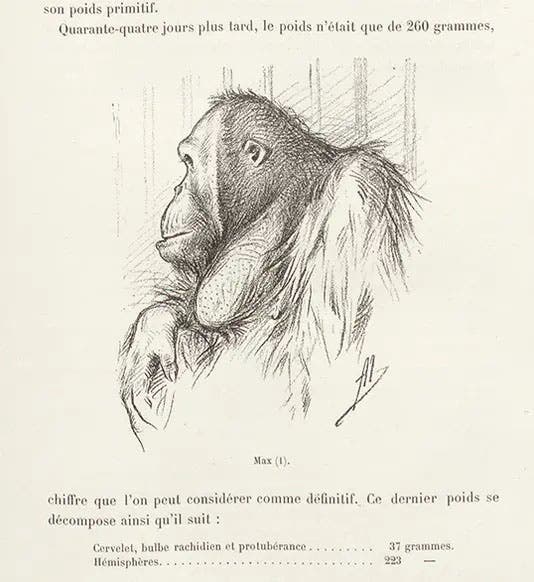

Max the orangutan, at the Paris menagerie, pencil-sketch by Adolphe Millot, in Nouvelles Archives du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, ser. 3, vol. 7, 1895 (Linda Hall Library)

Alphonse Milne-Edwards, a French zoologist, was born Oct. 13, 1835. Alphonse's father, Henri Milne-Edwards, was a star zoologist himself, being professor of zoology at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, which, in spite of its name, was as much a teaching institution as a repository. Alphonse would succeed his father in that position, as happened in France perhaps more than it should, although Alphonse was certainly well qualified for the job.

In 1868, Alphonse began to get letters from Father Armand David, a French missionary who had gone to China to save souls and sacrifice more than a few animal and plant specimens for the benefit of science. One of Father David's letters was accompanied by a large black-and-white pelt and a skull from an animal heretofore unknown to the West. David thought it was some kind of bear, and called it Ursus melanoleucus, the black-and-white bear. Alphonse, being the expert, naturally had to disagree, believing that it was more closely related to the little red panda, and in his published description, Alphonse named it Ailuropus melanoleucus, the black-and-white panda, and proclaimed it closer to a raccoon than a bear. The description appeared in his Recherches pour servir l'histoire naturelle des mammifčres (1868-74), a work we dearly wish we had in our collection, but alas, do not, so I show you the published chromolithograph from the copy in the Smithsonian Institution Libraries (third image). The debate about the giant panda's proper kinship, bear or raccoon, raged for the next century, until genetic analysis recently determined that the good father was right after all (sacerdotal infallibility?) and the giant panda is a bear, and barely related to the red panda.

Alphonse did better on most of his other descriptions, especially with the singular mammals of Madagascar, about which he contributed to the Histoire physique, naturelle et politique de Madagascar (1875-1954); indeed, several lemurs are named after Alphonse, including the Milne-Edwards sifaka. We do not have this work in the library either.

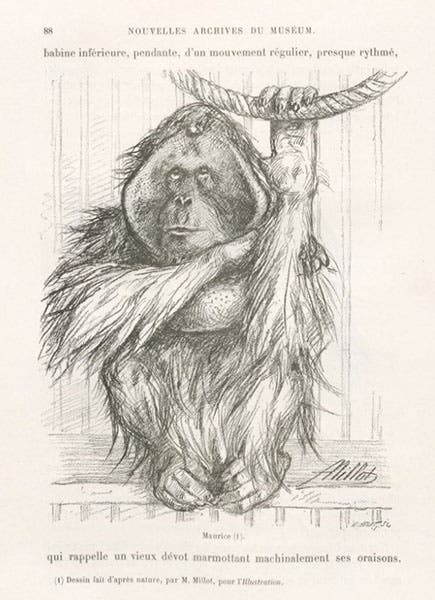

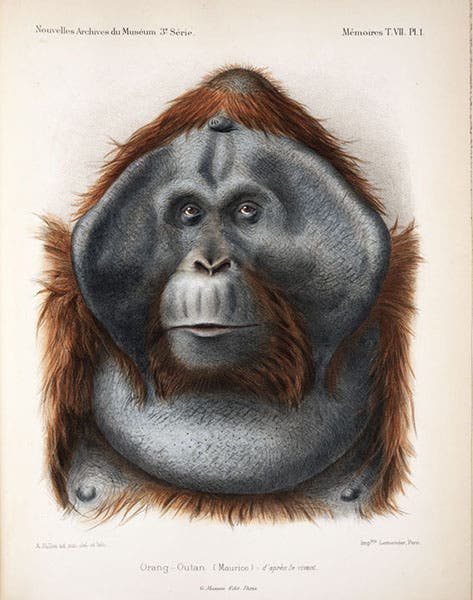

Fortunately, we do have a run of the Archives of the Paris Museum of Natural History, the annual publication in which new discoveries were customarily announced before they appeared in later monographs, and each volume included at least three or four attractive hand-colored lithographs. Alphonse, perhaps because of his Madagascar studies, had a particular interest in primates, and the Paris menagerie in the Bois de Boulogne in the late 19th century had a pair of orangutans that delighted the public – Maurice, an older male, and Max, the young stud – until they both unfortunately died. Milne-Edwards edited and wrote the preface for an in memoriam for the orangutans in the Archives for 1895, which was accompanied by illustrations of Max and Maurice by the Museum illustrator, Adolphe Millot.

Millot provided two kinds of images. For the text, he offered four sketches of the orangs that showed them if what we are tempted to call thoughtful poses. We show two of them here. Our opening image shows Max in his cage, and the image above depicts Maurice, also in his barred home.

And then, at the end of the various articles on the orangutans, there are two colored full-page plates, and the most appropriate adjective for these is “eye-popping”. I don’t think any of the great apes had ever made a more forceful appearance in scientific literature than these dual portraits of Max (sixth image, above) and wonderful Maurice, in all his cheeky splendor (seventh image, below). I suspect that the in-your-face poses were inspired by, and perhaps a tribute to, the wonderful lithograph of a chimpanzee by Marie Firmin Bocourt, printed 37 years earlier in the very same Archives of the Paris Museum, which we used in the catalog of our Grandeur of Life exhibition in 2009.

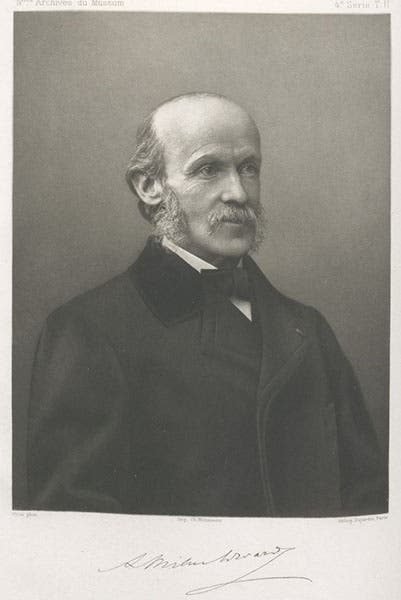

When Milne-Edwards died in 1900, the Archives published a memorial portrait, as they usually did for recently deceased members of the Museum faculty. It was a photograph, printed as a heliogravure. I never tire of heliogravure portraits – they are so rich and warm, even in black and white, and they put all modern methods of printing photographs to shame. We show the heliogravure of Alphonse Milne-Edwards as our second image.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.