Scientist of the Day - Ambrogio Soldani

On June 16, 1794, a shower of stones fell from the sky just outside Siena, Italy. The many eye-witnesses agreed that a dark cloud had rapidly approached out of a clear sky, exploded like a battery of fireworks, and ejected the stones, which fell with a hissing sound. At the time, most scientists thought that tales of stones falling from the skies were mere peasant inventions. The German physicist Ernst Chladni, a few months before the Siena fall, had written a book making the case for the extra-terrestrial origins of meteorites, but he found no takers. After the Siena fall, Abbé Ambrogio Soldani, an Italian naturalist, interviewed witnesses and collected 19 of the fallen stones; he also sent one stone to an English chemist working in Italy, William Thomson, who analyzed it. Both Soldani and Thomson agreed that the stones had a fusion crust that must have been produced by extreme heat, and that they contained a great deal of iron, which made them quite unlike the other rocks of the Siena countryside

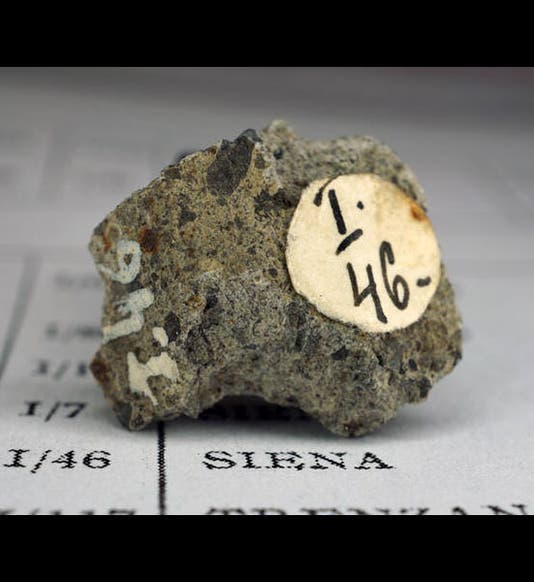

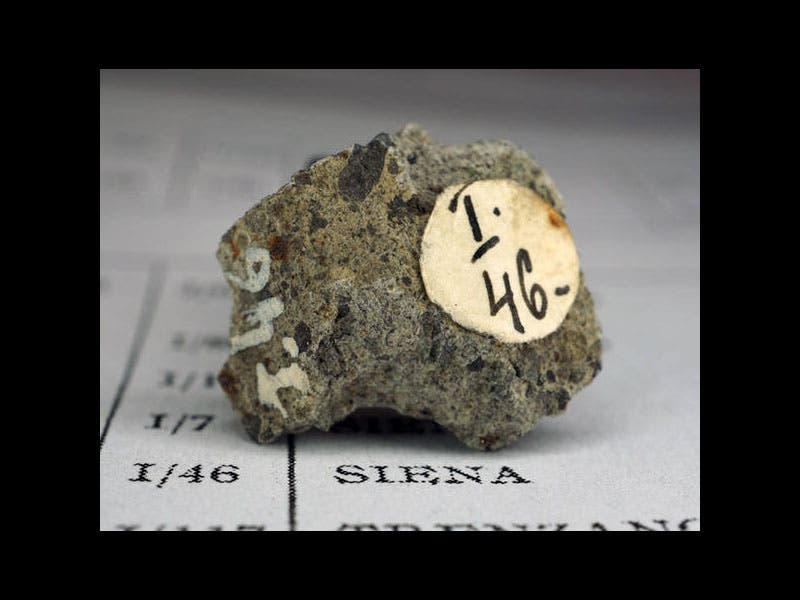

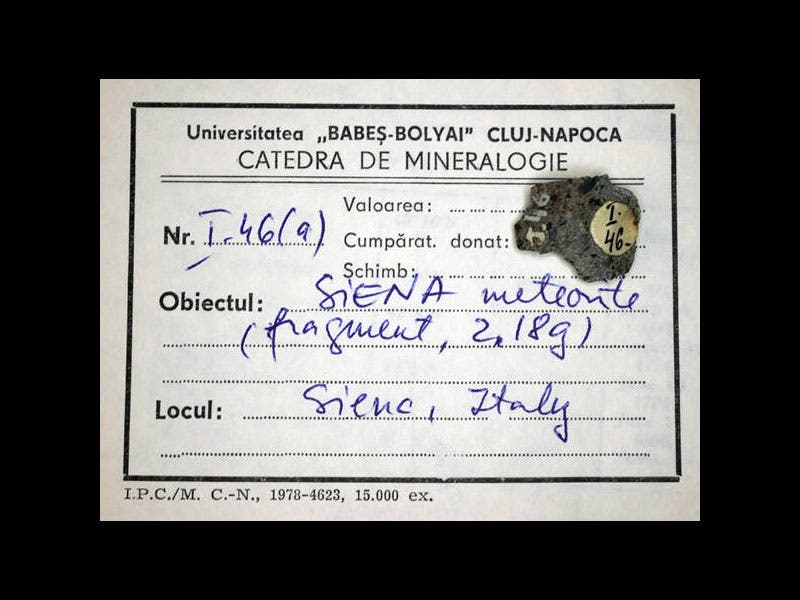

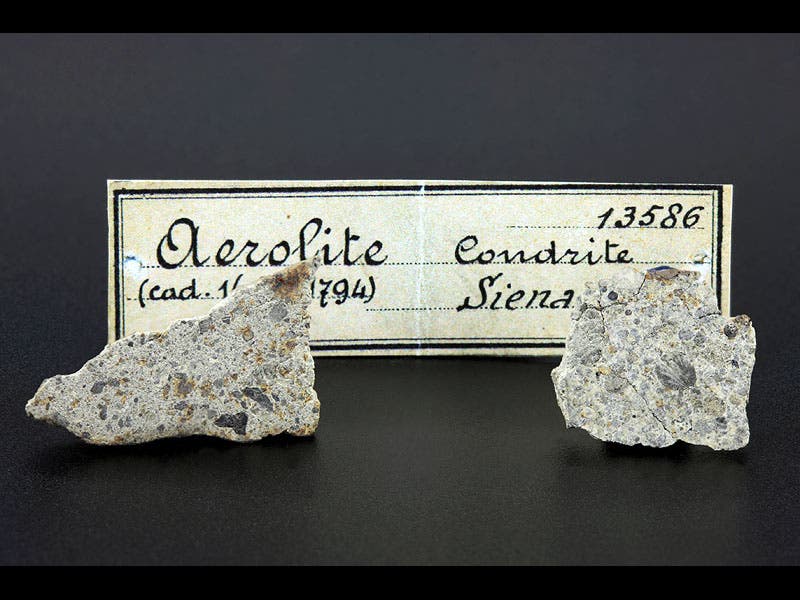

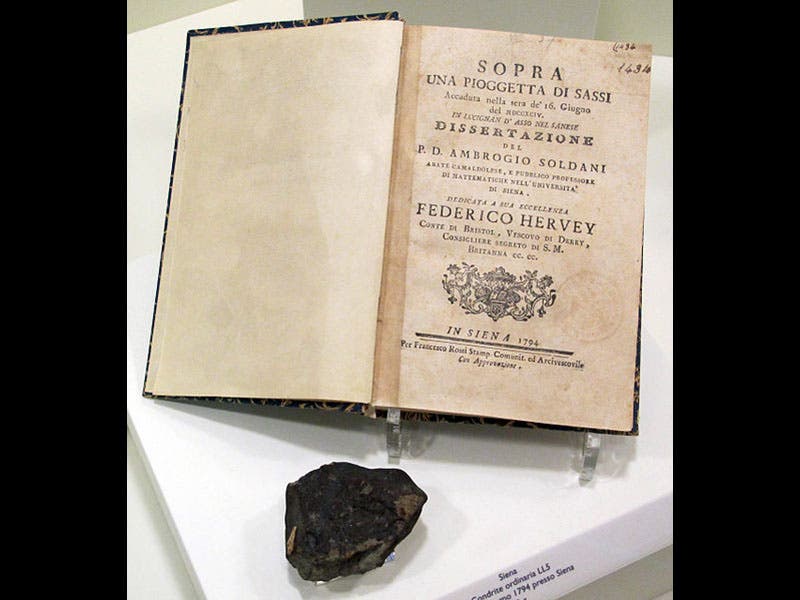

Later that year, Soldani published a book, Sopra una pioggetta di sassi accaduta nella sera de' 16 Giugno del MDCCXCIV, that presented his arguments and Thomson's evidence that the Siena stones really had come from the heavens. This book, along with Chladni's, launched the science of meteoritics, and nine years later, the great fall of stones at L'Aigle France, and the study of these meteorites by Jean-Baptiste Biot, confirmed all that Soldani and Chladni had suggested. You can see several of the Siena stones above; the first two images show a very small fragment (and its card) in a private collection; the third image shows two fragments in Florence, and the fourth a larger stone, placed near a copy of Soldani’s book, opened to the title page. We have all of the relevant works by Soldani, Chladni, Thomson, and Biot in the History of Science Collection.

The two great collections of meteorites in the world are at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and the Natural History Museum of Vienna. The latter has at least one of the Siena meteorites, and its displays are pictured above (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.