Scientist of the Day - Amédée Guillemin

Amédée Guillemin, a French science writer, was born July 5, 1826. Guillemin wrote a number of works of popular science between 1866 and 1886. He wrote books on the heavens (1866), the Moon (1868), and the Sun (1873), all of which were beautifully illustrated and well received. Five years ago, wrote a post featuring Guillemin and his book Les cometes (1875), along with its English version, The World of Comets (1877), both containing handsome chromolithographs and wood engravings, a post you may consult if you want to see lovely illustrations of historic comets.

Today we return Guillemin to the limelight so that we can sample one of his books on physics, Les phénomènes de la physique (1868). We have a second edition (1869) of this work in French in the Library, but for this occasion, we are going to feature the first English translation, The Forces of Nature (1872), for reasons explained below.

The book covers the complete gamut of the physical sciences with frequent forays into the history of physics, illustrating the subject matter with 455 text engravings and 11 colored lithographs. Usually, when we must pick 6 or 7 images for one of our posts, we choose the illustrations in color, as we did with our post on Guillemin's comets, since the chromolithographs are so striking. This time, we will show several of the color plates, but more of some of the black-and-white wood engravings.

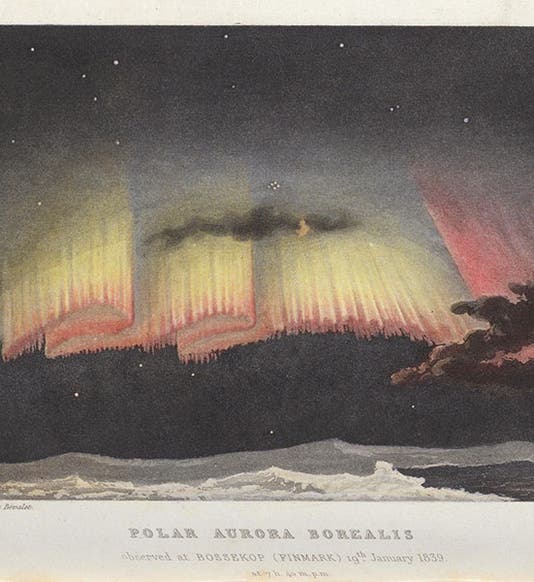

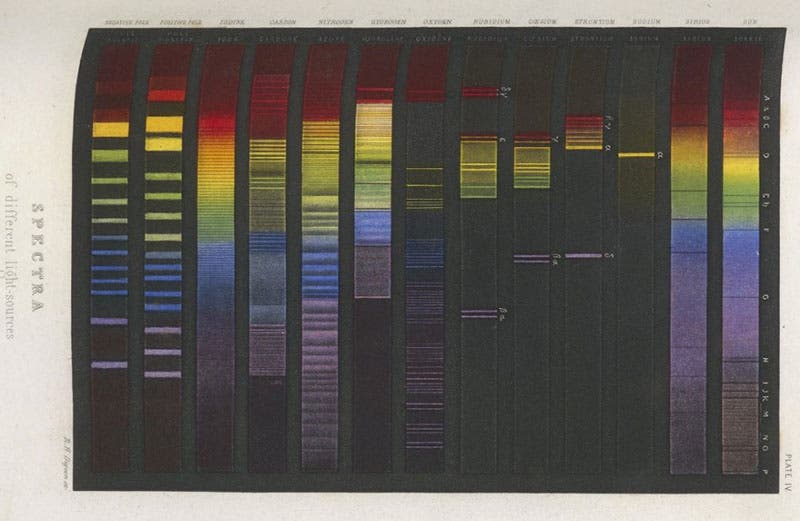

The most striking illustration in the book displays a “Polar Aurora Borealis,” and we open with that image. The plate showing various spectra is also colorful, as spectra usually are. (second image). We rotated the plate 90° from its book orientation so one can more easily read the spectrum labels at the side (now the top). Spectra of two stars are at the right, the Sun and Sirius, and the rest show the spectra of various elements, with the twin yellow lines of sodium next to the Sun. Oxygen’s spectrum is about in the center.

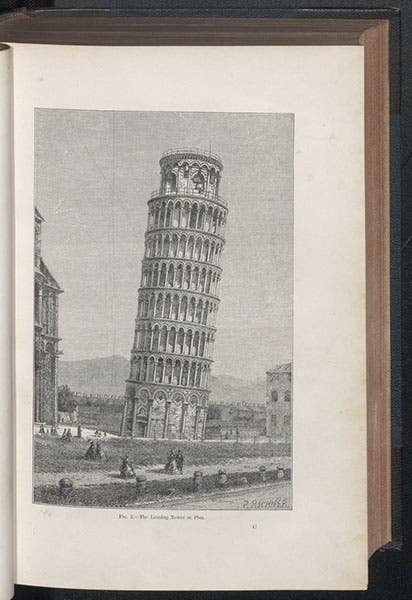

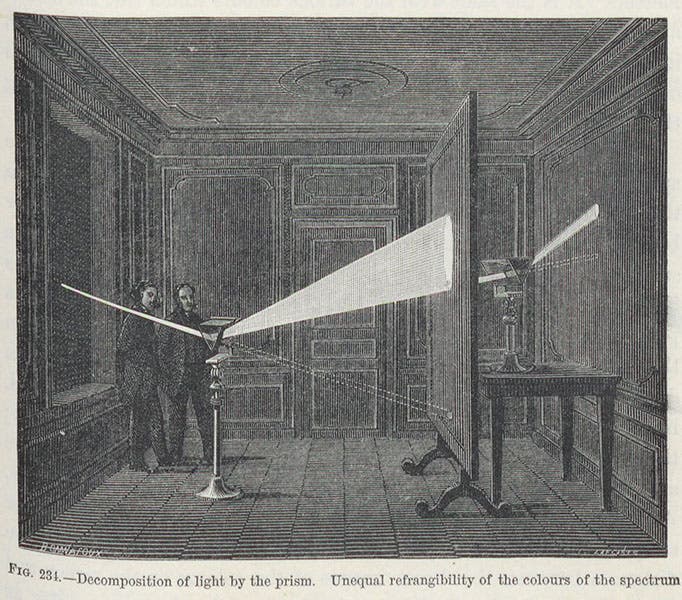

The next three images we chose are historical, and they are all wood engravings. The first is a fine view of the tower of Pisa, included because it was then thought that Galileo dropped objects off the tower to demonstrate that all falling objects accelerate at the same rate (fourth image, above). Another wood engraving (fifth image, just above) recreates Isaac Newton’s famous “experimentum crucis,” in which Newton hypothesized that a prism breaks white light up into its constituent colors, and then demonstrated that by sending the red light through a second prism, which redirected the light but failed to alter it further – it was still red.

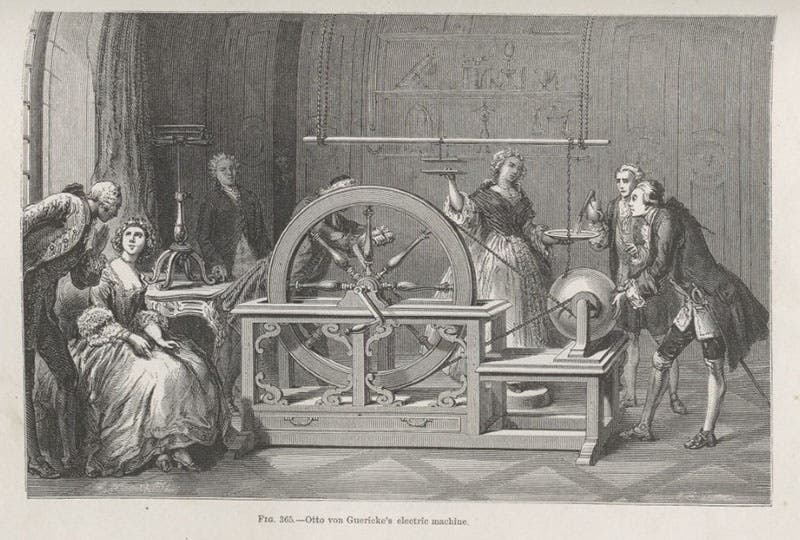

The third of these wood engravings is a mistake, which often happens in encyclopedic popular works (sixth image, just above). The caption claims that the image shows Otto von Guericke’s electric machine. But in fact, it shows Abbé Nollet’s re-creation on paper of Francis Hauksbee’s electrostatic generator, which is really unlike either Guericke’s or Hauksbee’s machines. You can see the original appearance of this illustration in an old post on Nollet. You can see what Hauksbee’s machine really looked like in a more recent post on Hauksbee.

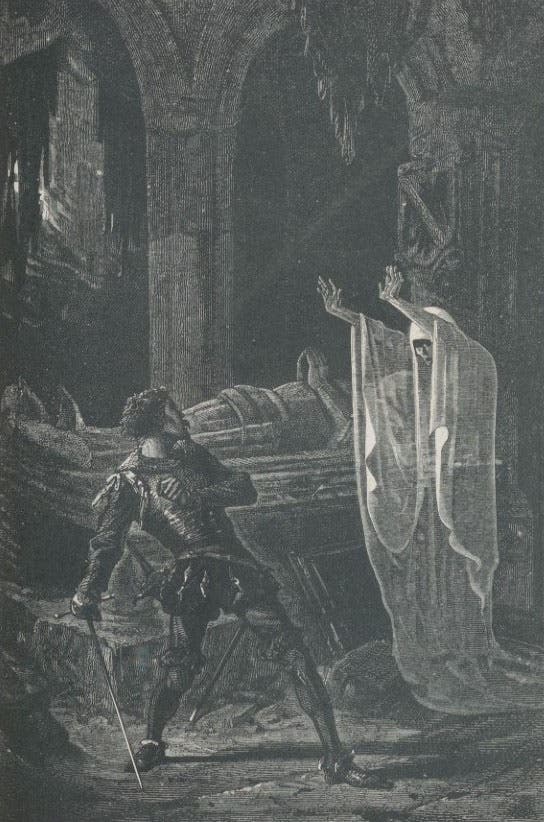

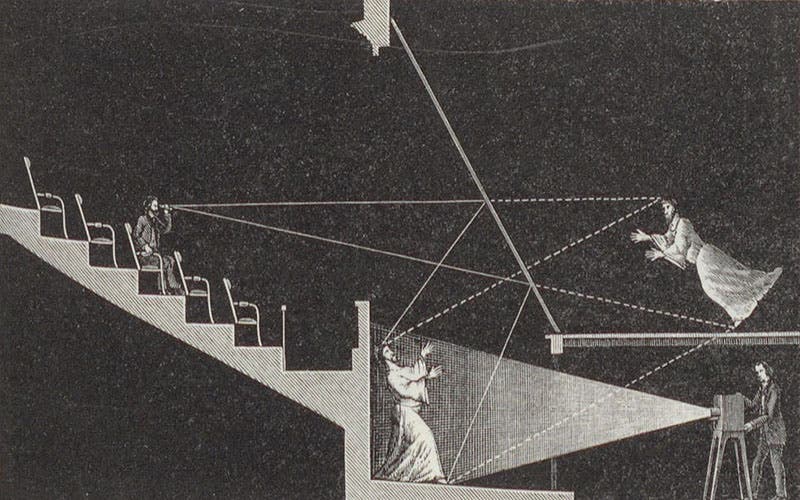

The last two illustrations I show are my favorites, because they depict a stage illusion that had only recently been devised, and which you won’t find in most popular books on physics. It was invented by Henry Dircks in 1862 but required elaborate apparatus; it was simplified and popularized by John Henry Pepper in 1863 and has been called “Pepper’s ghost” ever since. In the illusion, the audience sees a human ghost on stage, moving and reacting to an actor who really is on stage (seventh image, just above).

The illusion is generated by a hidden actor below stage level, on whom a bright light is focused, so that his image is reflected upward, toward the stage (eighth image, just above). Between him and the stage is a sheet of glass, which reflects the “ghost’s” image out toward the audience. They see him as if he is on stage. The two images in Guillemin’s book show the illusion as the audience sees it, and as it is generated. In the second illustration (eighth image), the thick diagonal line that runs from the stage up to the ceiling is the sheet of glass in cross-section.

We decided to draw on the English translation of Guillemin’s book, rather than the French original, because of the editor and translator. The editor was Norman Lockyer, a noted English physicist and spectroscopist, who had earlier (1868) co-discovered the element helium in the spectrum of the Sun, long before it was found on Earth (1895). The translator was his wife, listed on the titlepage as Mrs. Norman Lockyer, whom we prefer to refer to as Winifred James Lockyer. She also translated Camille Flammarion’s Les merveilles célestes into English. We have that translation, Marvels of the Heavens (1872) in the Library as well.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.