Scientist of the Day - Anaximander of Miletus

Anaximander of Miletus was a pre-Socratic philosopher who lived in Miletus in Ionia, a collection of Greek cities on the western coast of Asa Minor. He was born about 610 B.C.E. and died around 545 B.C.E. Along with his teacher, Thales of Miletus, and his pupil Anaximenes, Anaximander is considered one of the founders of Western philosophy and Western science. We have recently written posts on Thales and Anaximenes.

Thales had launched the Milesian school by asking, what is the fundamental substance out of which the universe was fashioned. He broke with the mythopoeic view of the Babylonians and the archaic Greeks by carefully not asking, who made the universe, and why? With Thales, it was all what and how? Making no reference to the idiosyncrasies of the gods, Thales sought only rational explanations without reference to things supernatural. Thales suggested that the most probable fundamental substance was water, since it seems to be everywhere, and it necessary for life. Anaximenes, the junior member of the Milesian school, later offered air as an alternative fundamental substance.

Anaximander, however, took an unprecedented step. Instead of turning to existing elements such as water and air as candidates for the fundamental stuff of the world, he proposed that such a substance might be more primitive than existing matter, perhaps some sort of primordial matter than lacked the defining properties of existing elements. So Anaximander suggested that the fundamental substance out of which everything arose was what he called apeiron, which we will leave in transliterated but untranslated Greek. We do so because apeiron means “the unlimited,” or better, “the undefined” – that which has no defining properties. I have always admired this philosophical step, because it took philosophy to another level, and suggested that truth may lie in aspects of the world that we cannot directly perceive.

Anaximander was also the first known Greek to propose a cosmology based on geometry. Most cosmologies before Anaximander had the Earth resting on something, because otherwise it was thought it would fall. Thales had suggested that the Earth floats on water, so the water keeps the Earth "up." You could just as well propose that the Earth sits on the back of a giant turtle. Anaximander took the bold step of claiming that the Earth resides in the center of the Cosmos because there is no reason for it to be anywhere else. It doesn't sit on anything. It is rather central to everything else. The Earth is shaped, he proposed, like a drum or a section of a column, about three times wider than it is high, with the oecumene, the inhabited world, residing on one of the flat faces. Three wheels, which we might imagine as bicycle rims, circle the Earth; they are filled with fire, with holes in the rim, through which we see what we call the Sun, the Moon, and the Stars. To accompany his cosmology, Anaximander is supposed to have constructed a map of the oecumene, the first Greek world map ever. Nothing of that map survives, if it was ever committed to vellum.

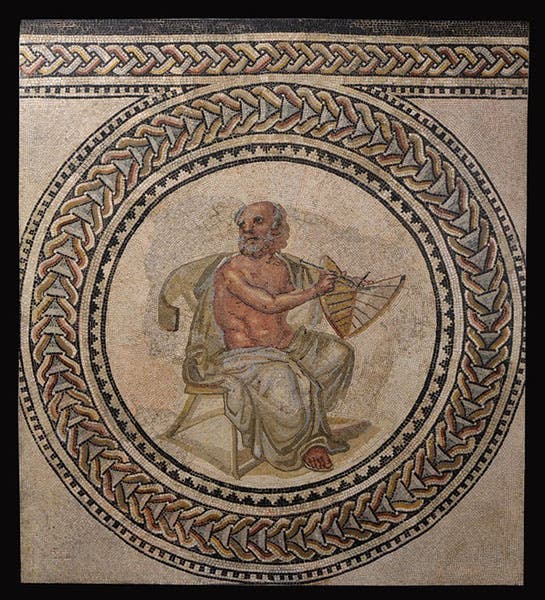

“The complete works of Anaximander,” in Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers, by Kathleen Freeman, Harvard Univ. Press, 1971 (author’s collection)

Before I go further, I wish to return to a subject that occupied our attention when we wrote about Thales and Anaximenes, and that is the paucity of documentation we have available when we talk about the Milesians. Thales wrote nothing; Anaximines wrote a book, of which one sentence only has come down to us. To write about these two, we have to rely on the doxographical tradition – what scholars such as Aristotle and Plato had to say about them, even though they wrote 250 years after the decline of Miletus. It is all we have.

With Anaximander, we are not much better off. He is supposed to have written a book, but it does not survive, and we don't even know the title. There are five fragments that later writers extracted from his book and that have come down to us; we show you all of them as printed in a book we introduced in our post on Thales, The Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers (1971), compiled and translated by Kathleen Freeman. We have captioned our third image "The complete works of Anaximander," because that is literally all we have of this founding philosophical father.

The first fragment is fairy substantial, a long, multi-clause sentence, which you should read, because it does (with the next two fragments) provide direct evidence for Anaximander’s concept of apeiron. And the last fragment seems to support his idea that the Earth is shaped like a drum from a column. But for the cosmology, the only evidence comes from Theophrastus, a pupil of Aristotle, who wrote a book discussing Anaximander. However, Theophrastus’ book is also lost, and we have to rely on an even later writer, Simplicius, who did have access to Theophrastus’s book. So it is a very thin and tenuous trail that scholars have had to try to follow in their quest for the true Anaximander.

Dust jacket, Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology, by Charfles H. Kahn, Columbia Univ. Press, 1960 (author’s collection)

I own two books about Anaximander. The more venerable is called Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology (1960), by Charles H. Kahn (fourth image). It is invaluable to those trying to sort out the doxographic tradition on Anaximander, because every word of it is here, in the original Greek, and fully evaluated and scrutinized. It is 250 pages long, and I marvel that Kahn could write so much about a man who has left us only a few sentences that set down just a few of his thoughts.

The other work is called Anaximander and the Architects (2001), by Robert Hahn (fifth image), which argues that Anaximander might have picked up the idea of applying geometry to the world and the cosmos from Greek architects, who from about 625 B.C.E. on, were building monumental temples in Miletus and Ephesus, using ground plans and geometric diagrams that might well have inspired Anaximander. Hahn even goes into great detail in describing the process by which builders made drums for their columns, carefully polishing the rims but leaving the rest rough and slightly concave, so the drums will fit together, and suggesting that the patterns of circles on the faces of the drums might have inspired Anaximander’s world map. I am not capable of evaluating a book that applies Greek architectural practices to Ionian philosophy, except again to be slightly skeptical that we can erect such elaborate explanatory schemes from such a paucity of real evidence.

Front cover, Anaximander and the Architects, by Robert Hahn, SUNY Press, 2001 (author’s collection)

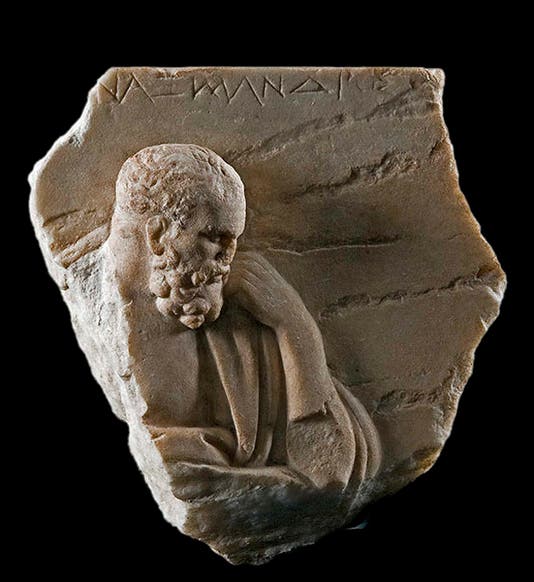

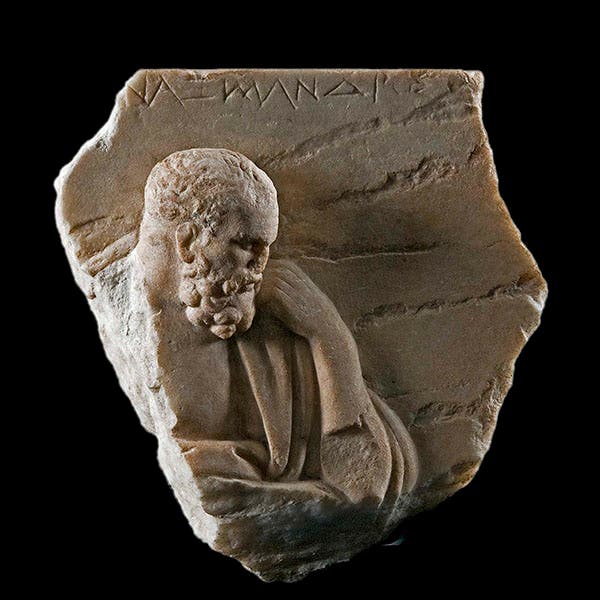

As with Thales and Anaximenes, there are no reliable portraits of Anaximander. We include here two that date to long after his death – a relief, from pre-Christian times, with his name inscribed, now in the Museo Nazionale Romano in Rome (first image); and a mosaic dating to the 3rd century C.E., in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum of Trier (second image).

Miletus disappeared into the Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus the Great about 550 B.C.E., but Milesian philosophy lived on, and the next interesting step occurred when a philosopher named Heraclitus, who lived in nearby Ephesus, speculated on the nature of change, and left hundreds of fragments that allow us, for the first time, to get a glimpse of the personality of an Ionian philosopher. Meanwhile, I will try to figure out how and when to introduce the elusive Pythagoras and his followers.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.