Scientist of the Day - Anders Sparrman

Anders Sparrman, a Swedish naturalist, died Aug. 9, 1820, at the age of 72. He studied with the great Carl von Linné (Linnaeus) at Uppsala University, went on a voyage to China after graduating, and then, in 1772, he headed for the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to study the local flora and fauna. As it happened, Captain Cook dropped by the Cape later that year, as his second voyage around the world was getting under way, and he invited young Anders aboard as an assistant naturalist. When the ships returned to South Africa in 1775, on their way back home, Sparrman hopped off where he had earlier hopped on. But within a year, he was back in Stockholm, where he would hold a variety of academic and curatorial positions during the forty years that remained of his tenure on earth.

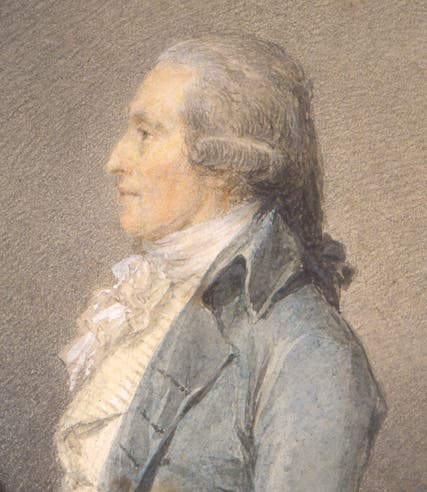

He is known for two publications, which appeared almost simultaneously. The first was a narrative about the Cook voyage, published in French and called Voyage au Cap de Bonne-Espérance, et autour du monde avec le Capitaine Cook (1787). It was soon translated into English as A Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope (1789), but the English edition omitted most of the 16 engravings that appeared in the French version. Not that this matters to us, because we do not have either edition in the Library. One of the published engravings in the French edition is notable as illustrating a great termite mound (second image). Sparrman was apparently the first European to see a termite mound sliced open, but because it took him ten years to get his narrative in print, he was not the first to publish such a picture; that honor goes to Henry Smeathman. We showed Smeathman’s termite mound in our post on Smeathman.

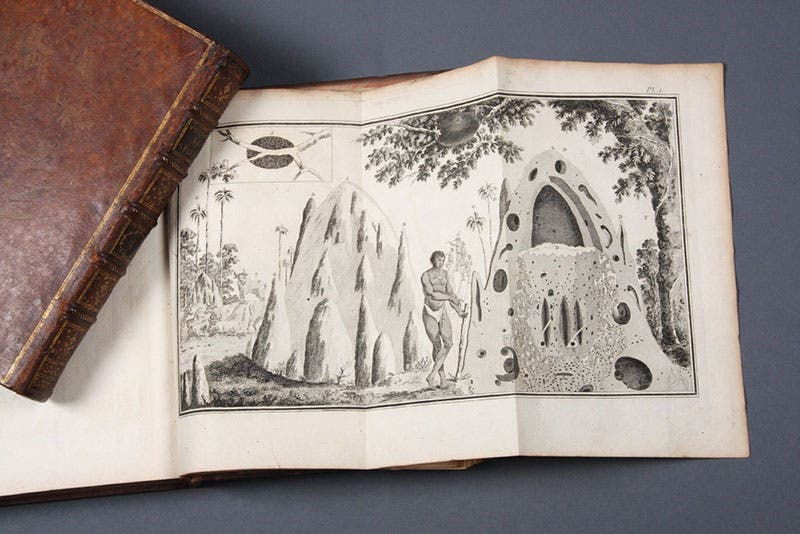

Sparrman's other notable publication stemmed from his friendship with Gustavus Carlson, the Swedish Secretary of State, who collected bird specimens from around the world, many acquired through the auspices of Sparrman. From 1786 to 1789, Sparrmann published Museum carlsonianum in 4 volumes, containing Sparrman’s descriptions and 100 hand-colored engraved plates of exotic birds. The birds were drawn by Jonas Linnerhielm and etched by Fredrik Akrel. The book is rather scarce and highly sought after by collectors. We do not have a copy in our collections. But the Smithsonian Institution Libraries has a fine copy, and they have considerately made the Museum carlsonianum engravings available online for the benefit of have-nots like us.

We show here, from the Smithsonian Libraries copy, a Magellanic or upland goose (third image), a white chaffinch (fourth image), and a detail of the plate of some sort of variegated thrush (fifth image). For those accustomed to the rich backgrounds in the bird prints of John Gould and John James Audubon, the Sparrman prints (which were published earlier) look rather sparse, but once you get used to the simplicity of the depictions, they tend to grow on you. Because hardly any of Sparrman’s binomial names are still in use, it is hard in many cases to identify the exact species depicted, and I have not attempted to do so. But I did want to comment on the way Linnerhielm depicted white birds, by framing them against a background of dark clouds (fourth image). There are three or four bird-against-clouds paintings in the Museum carlsonianum, and it seems to me a clever solution to a problem, solved differently later when bird artists such as Audubon began posing their light-colored birds against dark foliage.

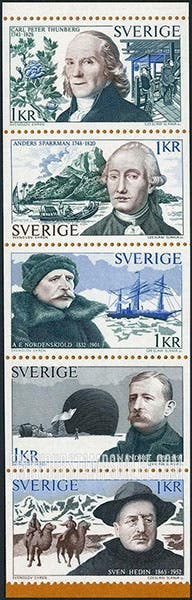

The Swedish government issued five postage stamps in 1973 to honor Swedish scientific explorers. Sparrman was the second in the series (sixth image). Of the others, we have written posts on A.E. Nordenskiöld and Salamon Andrée. Carl Thunberg and Sven Hedin await their turn.

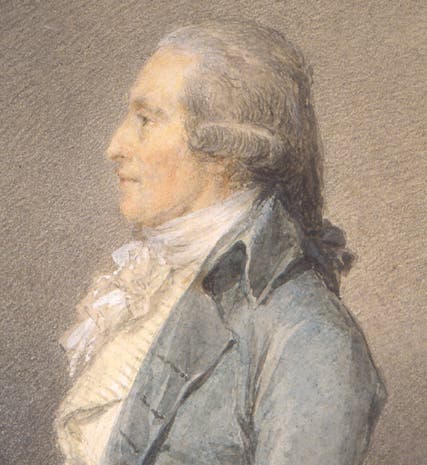

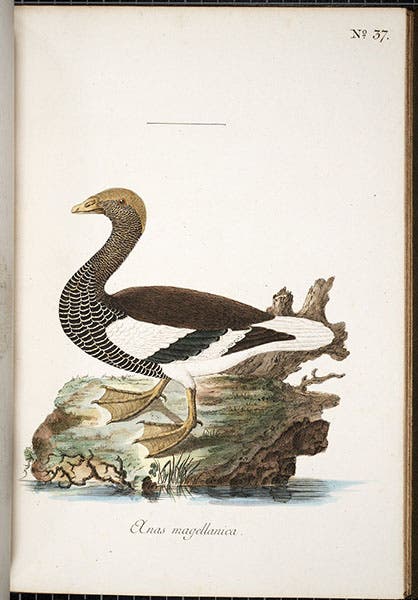

I would like to find out more about the beautiful pastel portrait that someone uploaded to Wikipedia (first image). It looks like Sparrman, so it is probably authentic, but the link provided is dead. If anyone knows where this portrait is, I would appreciate hearing from you.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.