Scientist of the Day - Andrew Carnegie

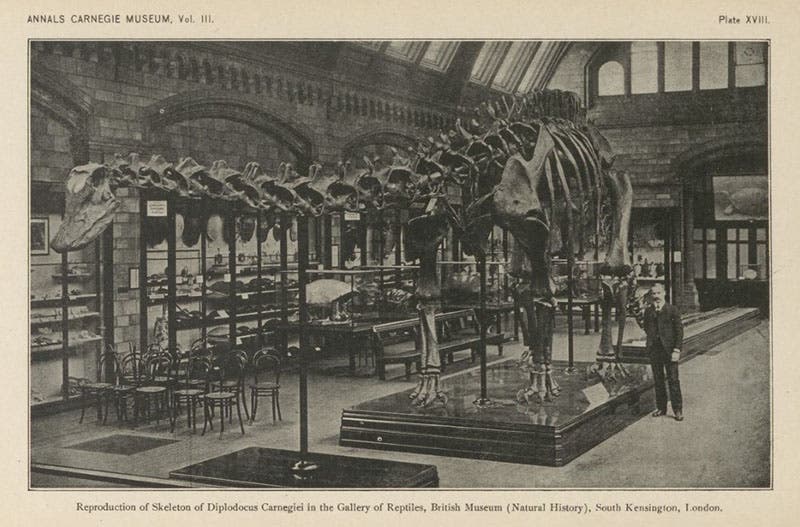

Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish-American industrialist, died Aug. 11, 1919, at age 83. After making millions in the steel industry (really billions, in modern dollars), Carnegie turned in his fifties to philanthropy. He had a special love for books and music, and he endowed hundreds of libraries around the country, and thousands of church organs. However, Carnegie also had a keen interest in science. He established the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh in 1895, and within four years he had acquired for the Museum the world's longest dinosaur, Diplodocus carnegiei. So proud was he of his elongated namesake (which he called “Dippy”) that he had molds made of every one of the bones, so that full-size plaster replicas could be made

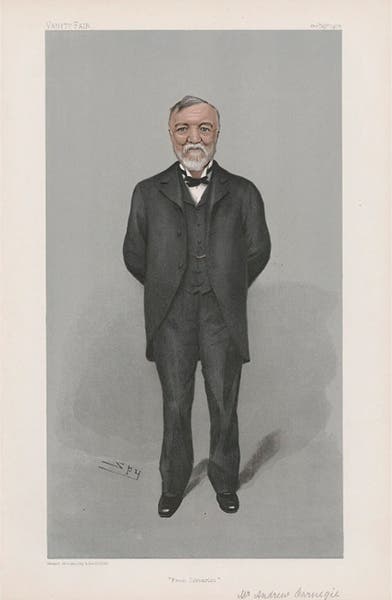

He is said to have gotten the idea for a replica when Edward VII, king of England, visited Skibo Castle in Scotland, the Carnegie ancestral home, saw an engraving ot the reconstructed skeleton with Carnegie’s name on it (in fact, the very engraving we show as our second image), and asked Carnegie to find another one for the British Museum. Since that was not too likely – Carnegie’s dinosaur diggers had gone through hoops just to get two partial skeletons – Carnegie offered to make Edward a life-size cast. He turned the job over to his right-hand man at the Carnegie Museum, William Jacob Holland, who put John Bell Hatcher in charge of the project, who turned the actual task of making the molds and the casts over to his assistant, Arthur Coggeshall.

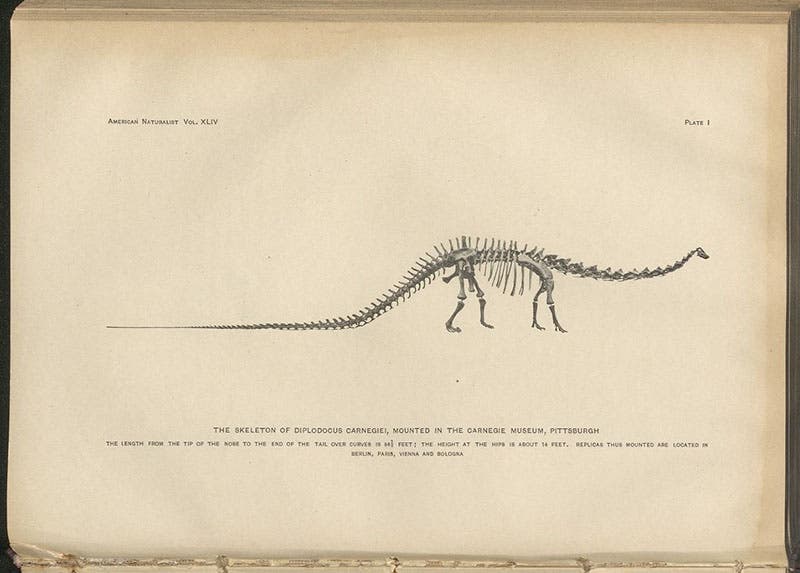

In May of 1905, Dippy 2 was unveiled in a formal ceremony in the Hall of Reptiles in what is now the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. Carnegie was disappointed that Edward VII was not present – he had taken great pains to pick a time when the king would be available – but he was content with Lord Avebury (John Lubbock), a good friend, doing the unveiling. There is a photograph of the ceremony in our post on Holland; here we show a photograph of the British Dippy when the crowds were absent, and from the other end, so you can see the head (third image). It is ironic that Dippy 2 had a home, but Dippy 1 did not – Carnegie was still waiting on the completion of an addition to the Carnegie Museum that was large enough to hold his namesake, and it would not be finished until 1907.

Once the molds were made, it was no particular problem to make additional casts, and over the next two decades replicas of Dippy were presented to museums in Berlin, Paris, Vienna, Madrid, Buenos Aires, and three other cities. Dippy in its 10 incarnations must be the most gazed upon dinosaur in history.

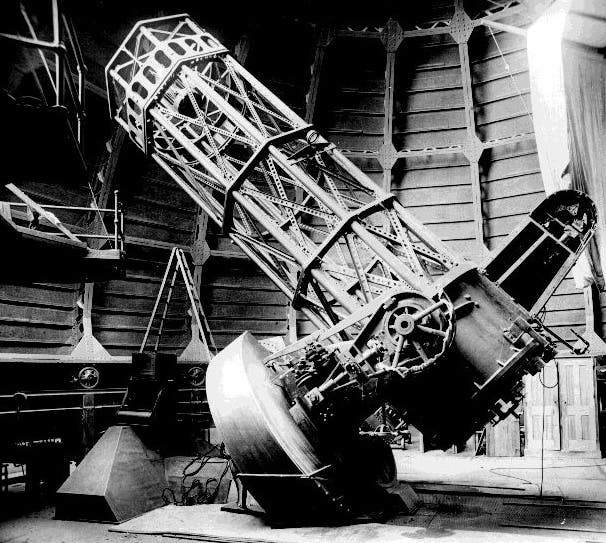

Dinosaurs were not Carnegie’s only scientific interests. He founded and endowed the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1902, to encourage basic scientific research. One of the Institution’s first projects was to build an observatory on Mount Wilson in Pasadena, California. Carnegie met and became good friends with George Ellery Hale, then at the University of Chicago, who was trying to come up with funding for a proposed 60-inch reflector, which would be the largest reflector in the world. Carnegie and his Institution told Hale that if he moved to Pasadena, they would foot the bill. There are several surviving photographs of Carnegie and Hale – I like the one included here (fourth image) where the two men are walking together in Pasadena (Carnegie is in the center, with the white beard and light suit; he holds Hale’s arm). The 60-inch Hale telescope saw its first light in 1908 (fifth image)

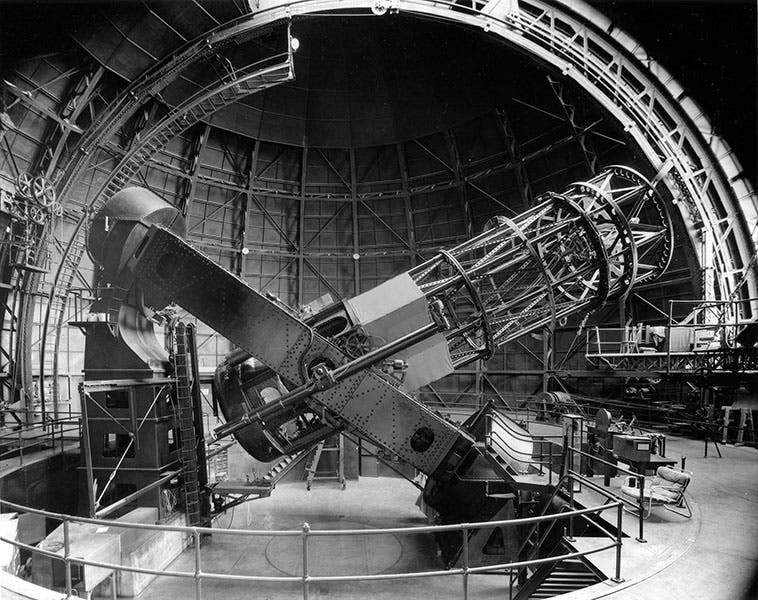

Even before the 60-inch was completed, Hale began planning for a 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson. He found a donor for the mirror – John D. Hooker, a wealthy hardware supplier – but he needed funding for the mount and the dome. In 1911, Carnegie gave an additional $10 million to the Carnegie Institution, with explicit directions that some of the money was to be used for Hale's giant telescope. Although Hale had nightmarish problems with the mirror (the glass blank, being cast in Paris, kept cracking in the cooling process), the problems were eventually solved, and the Hooker 100-inch telescope went into operation in 1917 (sixth image). Given that the mirror blank cost Hooker only $45,000, and that Carnegie and his Institution provided much more than that in funding, the telescope should really be called the Carnegie 100-inch reflector.

Should you want to see the London Dippy, be forewarned that they removed it from its perch in the museum in 2017, sent it on a grand tour to various British museums for 5 years, and have now parked it in a provincial museum in Coventry. Its place in the Natural History Museum has been taken by a blue whale. I am not pleased with this treatment of one of the most historic dinosaur mounts in the world. I suspect the ghost of Andrew Carnegie feels the same way.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.