Scientist of the Day - Andrew E. Douglass

Andrew Ellicott Douglass, an American astronomer, was born July 5, 1867. Although his principal claim to fame lies in archaeology, Douglass was an astronomer by profession, working first at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, and then, when he fell out with Percival Lowell over his Martian canal interpretations, at the University of Arizona in Tucson, where he oversaw the contracting and construction of the Steward Observatory and its 37-inch reflecting telescope, which had severe gestation problems during the First World War, but which finally opened for business in 1923.

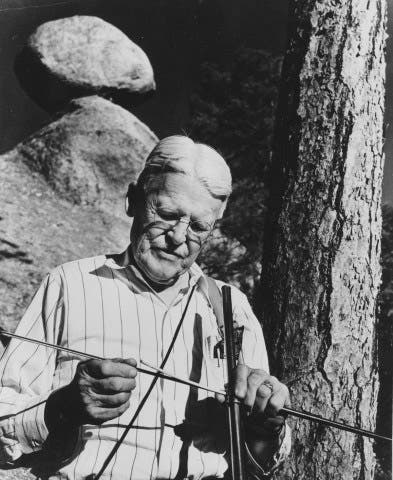

Douglass's particular astronomical interest was the 11-year solar cycle and its relationship to Earth's climate over time. To investigate any possible connection, one needs a precise climate calendar, one that tells you what the weather was like over a thousand years ago, over intervals as small as one year. It was supposedly while descending from the Kaibab plateau in a wagon that Douglass got to wondering about tree rings. It was known that tree rings record annual growth, and it was surmised that during years of abundant water, the rings were thicker than those grown during dry years. So perhaps the 11-year solar cycle might be reflected in tree-ring growth. But when Douglass began studying tree rings in 1904, it was not known whether the ring pattern was the same from tree to tree in one area, or in different areas, or how far back you could take a tree-ring calendar, if such a calendar indeed existed.

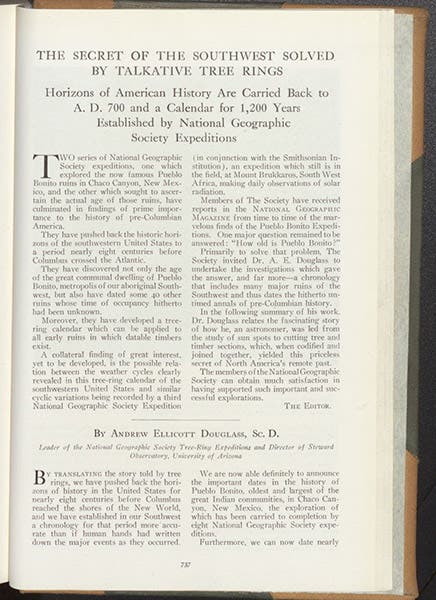

First page of "The secret of the Southwest solved by talkative tree rings,” by Andrew E. Douglass, National Geographic, 1929 (Dec.), vol. 56, no. 6 (Linda Hall Library)

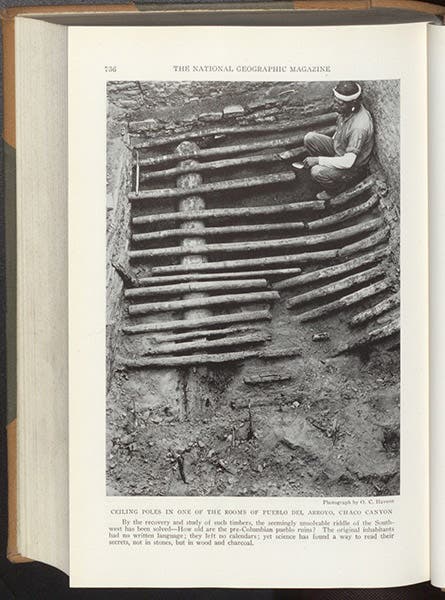

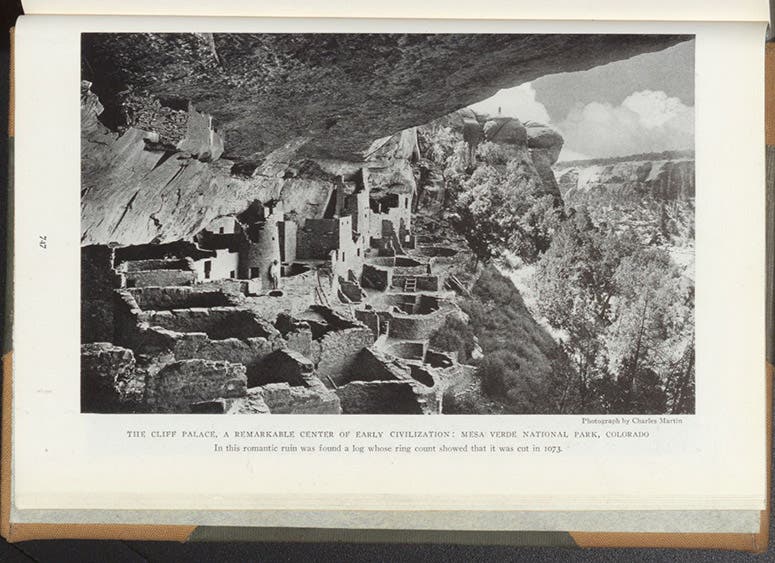

Douglass studied Ponderosa pines at first, and Douglas firs, and eventually graduated to the Giant Sequoias of California, which turned out to contain tree-ring calendars exceeding 3000 years. But his greatest achievement was in discovering how to overlap tree-ring patterns from different age trees and tree beams to build a continuous tree-ring calendar going back centuries. The states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado, contain dozens of ruins with wooden beams, usually of Ponderosa pine or Douglas fir (fourth image). No one knew how old these ruins were; many guessed for example, that the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde in southern Colorado were several millennia in age (fifth image). But if one could identify tree-ring patterns in the beams, they could be dated precisely.

Wooden ceiling poles at Chaco canyon, photograph in article by Andrew E. Douglass, National Geographic, 1929 (Dec.), vol. 56, no. 6 (Linda Hall Library)

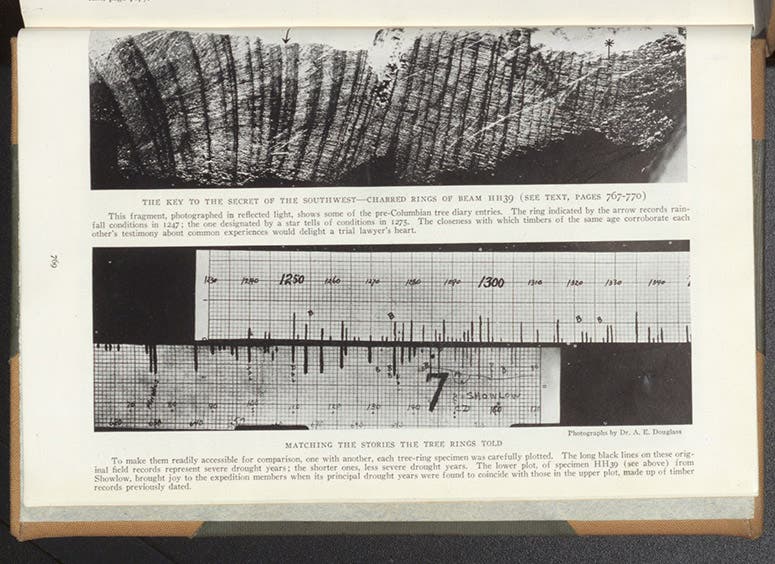

Douglass slowly developed two time-scales or calendars based on tree rings; one went back from the present to 1260 AD (or 1260 CE, as we would now call it). This was called the Flagstaff chronology. Another scale was compiled from wooden beams found at various Anasazi sites; it was 560 years long, but it did not connect up with the Flagstaff chronology; it was called the "floating chronology." In 1929, in a lushly illustrated article in National Geographic (third image), Douglass announced the discovery of a beam near the site of Show Low in Arizona, referred to as beam "HH-39", after its two discoverers, who worked for Douglass. The beam had a ring pattern on the outside (the more recent growth) that matched up with the beginning of the Flagstaff chronology, and an inner pattern that matched the tail end of the floating chronology (sixth image). The two were now spliced, and archaeologists suddenly had a calendar that went back to 700 CE. Chaco Canyon, Canyon de Chelly, and Mesa Verde could now be precisely dated. To everyone's surprise, the Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde turned out to have been constructed between about 1190 and 1260 CE, much more recently than anyone suspected. Archaeologists now had a dating tool that would prove invaluable, provided to them by Andrew Douglass, an astronomer. The new discipline was called dendrochronology, a term coined by Douglass.

Cliff House at Mesa Verde, photograph in article by Andrew E. Douglass, National Geographic, 1929 (Dec.), vol. 56, no. 6 (Linda Hall Library)

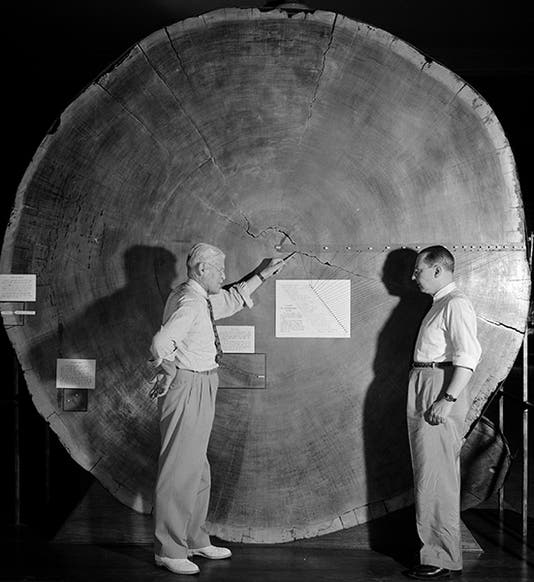

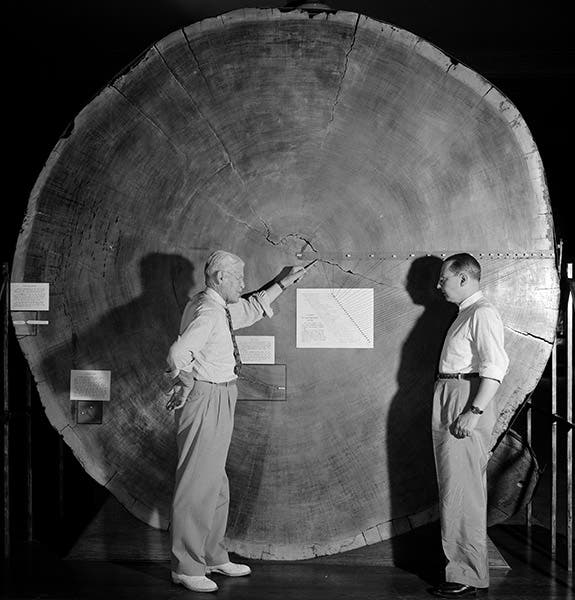

Several scholars have pointed out that the story of HH-39 is not only legendary, but also part legend, as Douglass had connected up the scales several years earlier – what he needed was corroborating evidence, and HH-39 provided just that. Nevertheless, HH-39 has been dubbed “the missing link” of archaeology and is an object of pilgrimage for archaeologists of the American southwest. It is preserved in a special environmental chamber in the Laboratory of Tree Ring Research at the University of Arizona in Tucson, which Douglass founded in 1937.

Beam HH-39, photograph, with a graph of its drought years matched up with the Flagstaff chronology, in article by Andrew E. Douglass, National Geographic, 1929 (Dec.), vol. 56, no. 6 (Linda Hall Library)

Douglass did publish more conventional scientific articles and monographs. His most important monograph was a three-volume set, Climatic Cycles and Tree-Growth: A Study of the Annual Rings of Trees in Relation to Climate and Solar Activity, published by the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1919-1936. I was excited to see an entry for this work in our digital catalog, but when I went to pull it off the shelf, I found, to my dismay, that volume 1 and 2 were in xerox, and only vol. 3 was original, a fact unmentioned in the catalog record. Sometimes these things happen in large libraries. The solution in this case will be not only to amend the record, but to find and acquire first editions of vol. 1 and 2.

Douglass lived a long and productive life, reaching the age of 94 before passing away on Mar. 2, 1962. He is buried in Evergreen Memorial Park in Tucson. I have not seen his gravestone, so I do not know if it has an epitaph, but a perfect one was provided by Stephen E. Nash in his 1999 book on tree-ring dating; he called his chapter on Douglass: “Lord of the Rings.”

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.