Scientist of the Day - Andrew Jackson Grayson

Andrew Jackson Grayson, an American bird painter, was born Aug. 20, 1818. Grayson grew up in Louisiana, moved to Missouri after his marriage, and then, in 1846, set out with his family on the great California emigration of that year. He settled in the San Francisco area and established the first of a series of general stores, which provided him with a great deal of wealth, part of which he spent on a family oil portrait in 1850, celebrating their arrival in California (second image). But Jackson's childhood passion was painting, especially wildlife, and more especially birds. His parents and early schoolteachers did their best to stifle his artistic impulses, but he started drawing again in the 1850s after moving down to San Jose. Then, in 1853, his wife Frances saw a set of Audubon's Birds of America on display in the Mercantile Library in San Francisco and urged her husband to take a look. Grayson was transfixed. He also noted that Audubon’s masterpiece was misnamed – it should really have been called "Birds of America East of the Mississippi". Grayson immediately conceived of the project that would occupy the rest of his days, a set of paintings of western birds, a sequel to Audubon, to which he gave the working title, "Birds of the Pacific Slope."

After painting some of the birds of California, Grayson made several trips to Mexico and ran across dozens of bird species that were unrecorded. In 1859, he and Frances moved to Mazatlán, and Jackson started to take an interest in the birds of offshore islands like Tres Marias and Socorro. His portfolio grew, and he began to correspond with Spencer Baird, the assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and the foremost ornithologist in the United States. Baird offered encouragement and welcomed the specimens that Grayson regularly sent to Washington, such as the pretty little Red Chat from the Tres Marias Islands, which Baird named Granatellus francescaea, after Frances Grayson, and which Jackson painted.

But Baird never offered financial support, although Grayson begged for it regularly. Grayson's financial affairs were in steady decline, since he no longer had a steady source of income. He wanted badly to publish his book, but he had no resources to pay for the expensive lithographs. Grayson went to Mexico City to the court of Emperor Maximilian, who promised to help publish the book, as did the Mexican Academy of Science, but when Maximilian was executed in 1867, the Academy withdrew its offer. Grayson came down with yellow fever about this time, and he recovered, but not enough, for he suffered a relapse and died in Mazatlán in 1869, just three days shy of his 51st birthday, his paintings still unpublished. His body was returned to San Francisco for burial.

Grayson’s widow Frances tried for many years to find a way to print her husband's life work, but she was unsuccessful, and she ultimately gave the watercolors and all of Jackson's field notes to the Bancroft Library at the University of California in Berkeley, where they sat, rarely consulted, for over a century. Grayson was probably the finest bird painter of his generation, and no one even knew who he was.

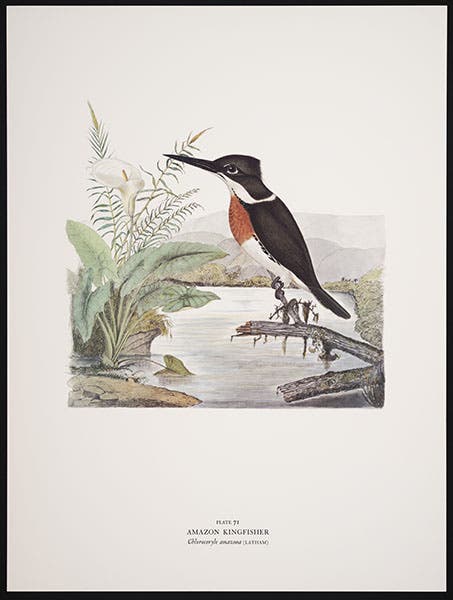

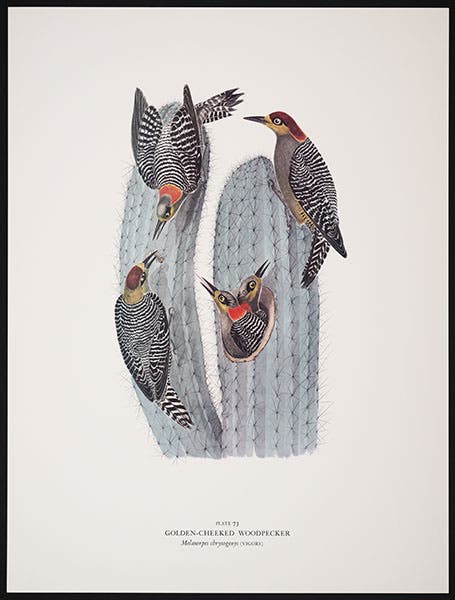

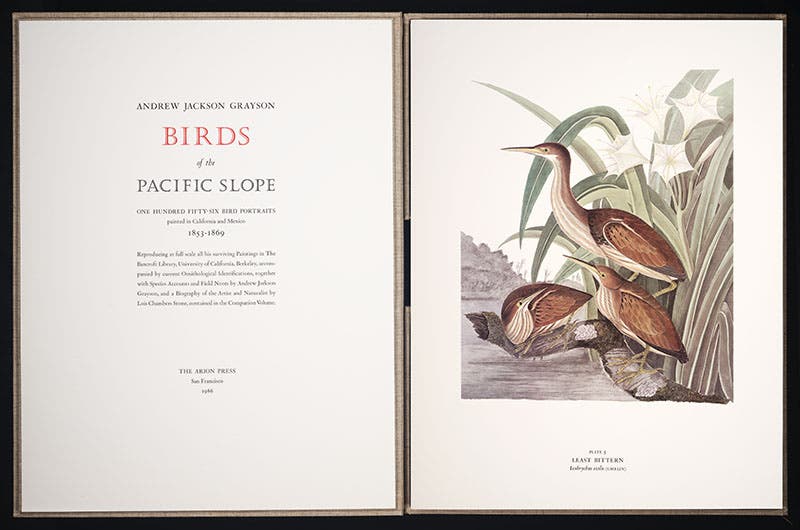

Fortunately, in 1986, the renowned San Francisco paragon of fine printing, the Arion Press, published all 156 of the surviving bird paintings in a large folio, calling it, as Grayson wished, Birds of the Pacific Slope, accompanied by a small folio volume containing a biography and the field notes. A set was given to our Library in 2014 by a private donor, and it now resides in our History of Science Collection. We chose 5 plates to illustrate this post: the Yellow-capped Night Heron (first image), the Amazon Kingfisher (third image), the Green Parakeet (fourth image), the Golden-cheeked Woodpecker (fifth image), and the Least Bittern (sixth image). The other 151 plates are just as remarkable.

We couldn’t resist snapping a shot of the enormous box of plates, with its letterpress title page and the Least Bittern plate on the top of the stack (sixth image, above).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.