Scientist of the Day - Annie Russell Maunder

Annie Russell Maunder, an Irish/English astronomer, was born Apr. 14, 1868. She was well-educated by her parents and took an early interest in observational astronomy. She attended Cambridge University and although she could not receive a regular degree, she did receive what amounted to an equivalent to a college degree, which distinguished her from most women in 1880s Victorian England who had aspirations to be an astronomer. Unfortunately, even for Annie, there was no possibility of pursuing astronomy professionally. The best she could do was get a job for a few years as a computer at the Royal Greenwich observatory. Greenwich was apparently trying to follow the model of the Harvard College women computers, but in this case it did not last. But it lingered long enough for Annie to meet, work alongside, fall in love with, and marry a male astronomer who was very much a professional, Edward Maunder. We published a post on Edward just two days ago.

Edward had little use for the stuffiness of Greenwich or the elitism of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), so he had no reservations about teaming up with Annie at Greenwich to study eclipses and sunspots. Annie could not join the RAS, but fortunately Edward had recently founded a new organization, the British Astronomical Association (BAA), which she was able to join, since they accepted women members, and which sponsored four eclipse expeditions made by the Maunders in the 1890s and early 1900s. Annie was a good photographer and observer, published papers on her work, and generally did what male astronomers did, except that she was kept by convention in the amateur category. She was, in the words of one historian, an obligatory amateur. Not until 1916 did the RAS break down and admit women to their ranks. But that was mostly a result of the tumult of the War, when men in England were hard to find. Annie was not the first to be admitted as a fellow, but she was admitted in that first year that women were eligible.

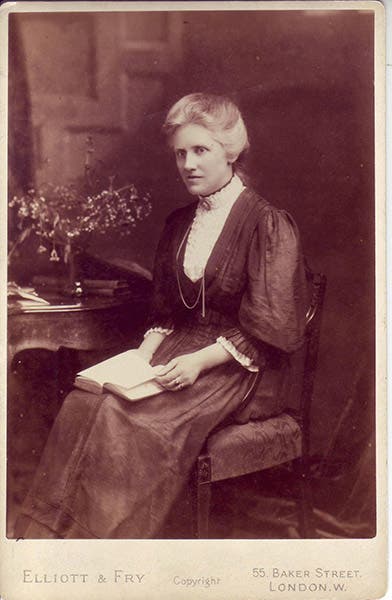

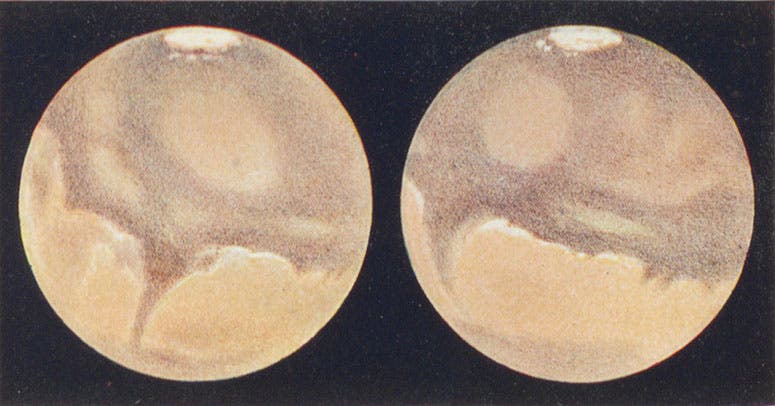

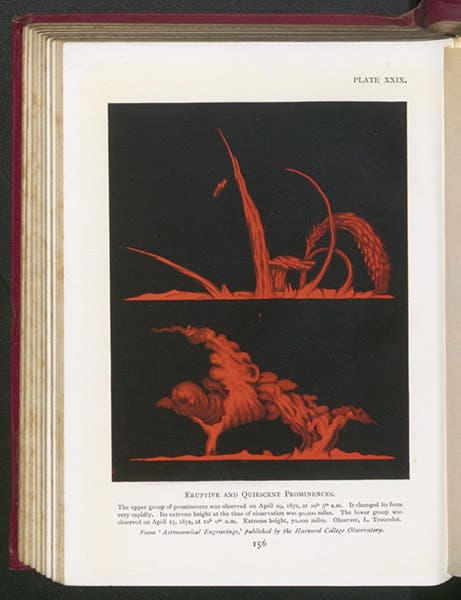

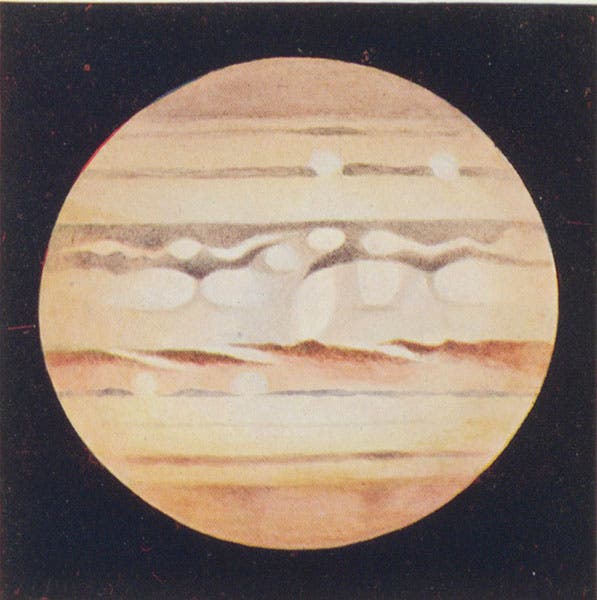

Today we are going to discuss a book that Annie wrote with Edward, called The Heavens and Their Story (1908), which we have in our special collections. It was a piece of popular science writing, intended for a public interested in astronomy, similar to the books of Robert S. Ball, the Irish astronomer who incidentally was a big fan of Annie and wrote a letter of recommendation for her when she was still trying to find a job within the astronomy profession. Annie's name is the first on the title page (fourth image), and in the preface Walter says the book was almost entirely Annie's work. Annie wrote well, but it is hard to demonstrate that here, so we will bear witness instead to her skill as a photo editor. With several exceptions, the illustrations were the work of others, but she chose very well. The best images of Mars available were those done by Nathaniel Green; she included four in the book, of which we include two here (second image). (The other great Mars observer of the time was Eugène Michel Antoniadi, and she included a color plate of one of his drawings as well). The paintings of Etienne Trouvelot were well-known at the time and were probably not to Annie's taste, being rather unrealistic in most cases, but I can see why she liked Trouvelot's rendering of solar flares (fifth image). Her image of Jupiter (sixth image) was provided by Theodore E.R. Phillips, who was chair of the Jupiter section of the BAA and would later coauthor a popular astronomy book of his own, Hutchinson’s Splendour of the Heavens (1923).

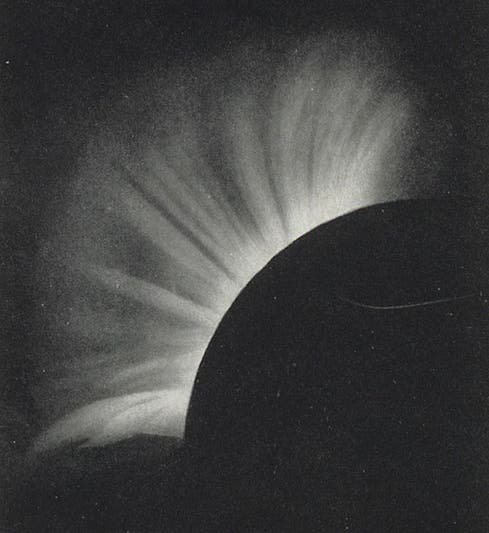

To me, the most interesting illustrations in the book are two that Annie did herself. They show the solar corona at the time of a total solar eclipse, in this case one that occurred on May 18, 1901, which she and Edward journeyed to Mauritius to observe. We show one of those here, as our lead image. The caption (cropped in our image) reads: "Southern region of the Corona of May 18, 1901, showing the polar 'plumes.' (From a photograph by Mrs. Walter Maunder, taken in Mauritius)."

And of course, a popular work of astronomy needs a colorful embossed front cover, which Annie and Walter certainly provided (seventh image).

Annie spent the rest of her life advocating for the importance of the amateur astronomer. Relegated to that status by her gender, she made a virtue of circumstance and embraced her fellow amateurs. She edited the Journal of the BAA for 13 years, and continued to publish in popular journals well after her husband’s death in 1928. She died on Sep. 15, 1947.

In 2018, telescopes returned to Greenwich Observatory when the Annie Maunder Astrographic Telescope was installed in the Altazimuth pavilion at Greenwich (eighth image, just above).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.