Scientist of the Day - Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine Lavoisier, a French chemist, was born Aug. 26, 1743. Lavoisier is rightly considered the father of the chemical revolution of the late 18th century, and he is remarkable for having achieved this stature without discovering a single new element or gas or any other natural phenomenon. Oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide were identified by others. What Lavoisier did was to reinterpret how these elements interact. Contemporary chemists invoked a substance called “phlogiston” to explain why things burn or rust; it was thought that phlogiston was given off when a substance burned. In 1778, Lavoisier proposed that oxygen was the key element; things burn by taking on oxygen, not by giving off phlogiston. Rusting is just a slower “oxidation” of an element.

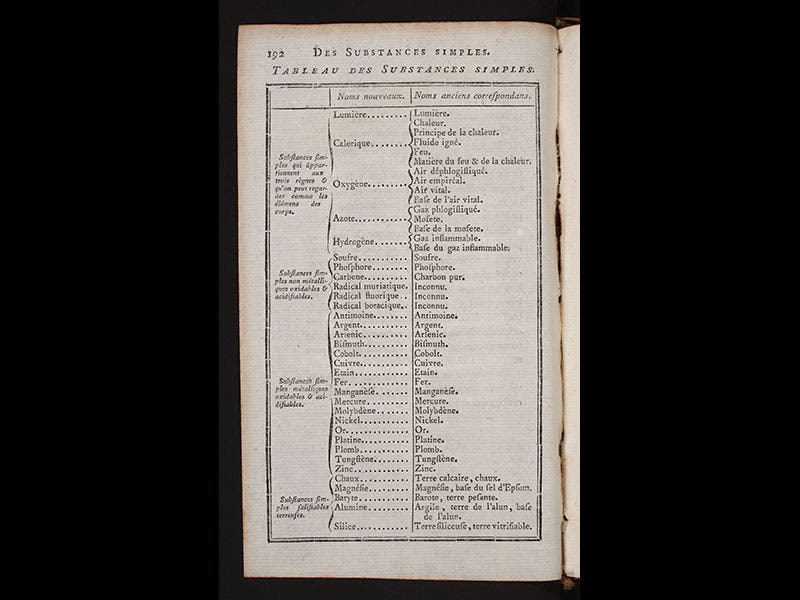

The oxygen theory of combustion turned out to have much more explanatory power that the phlogiston theory, especially since it explained why substances gain weight when they oxidize. Lavoisier later set down the first modern list of elements (second image), and he also reformed chemical nomenclature, dumping the colorful alchemical language of “flowers of sulfur” and “sugar of lead” in favor of carbonates and oxides and adjectives like sulfuric and nitrous. His collaborator in much of his work was his wife, Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, who also illustrated many of Lavoisier’s scientific publications. It is sad that she had to witness Lavoisier’s final fate. Lavoisier was a member of the Ferme-Générale, a tax collection agency, and he was arrested along with the other administrators during the Reign of Terror and executed by guillotine on May 8, 1794, at age 50. As a countryman said at the time, “It took only a moment to cause this head to fall, and a hundred years will not suffice to produce its like.”

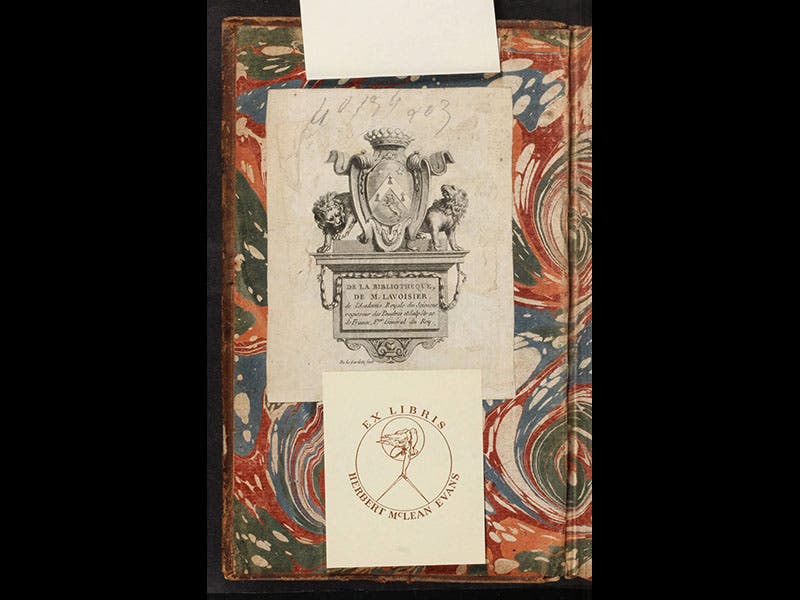

The first image above shows a reconstruction of Lavoisier’s laboratory at the Musée des arts et métiers in Paris. The third image is a double portrait of Antoine and Marie-Anne, painted by the great Jacques-Louis David in 1788; you can see it in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. We have nearly all of the works of Lavoisier in our collections, as well as numerous translations. An additional book in our Library, Rudolf Raspe’s Specimen historiæ naturalis globi terraquei (1763) has a bookplate indicating it came from Lavoisier’s Library; it also sports the subsequent ownership label of the great 20th-century physician and bibliophile, Herbert McLean Evans (fourth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.