Scientist of the Day - Anton Maria Schyrleus de Rheita

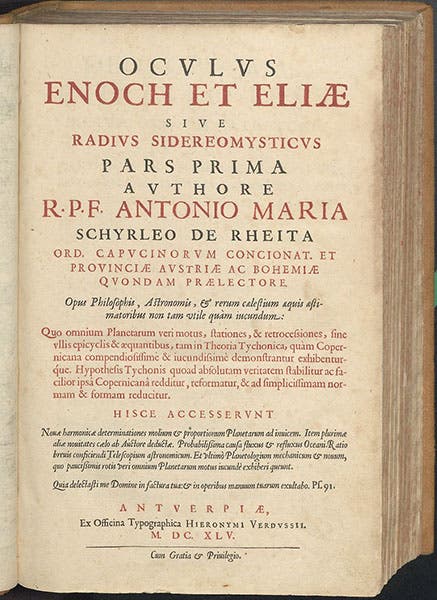

Anton Maria Schyrleus de Rheita was a Czech or Austrian Capuchin monk, who published a massive treatise on optics and astronomy in 1645. We do not know for certain the place or the year of his birth (1597 and 1610 have both been proposed), nor the day of his death, although he is said to have died in Ravenna in Italy, possibly in 1662. And there is no portrait of our Capuchin. All we really have to tell us about Anton Maria is his book, which was called Oculus Enoch et Eliae, sive Radius sideromysticus . An English translation may or may not be of assistance in trying to figure out what this book is about: The Eye of Enoch and Elijah, or the Starry Mystic Ray. It was published in 1645 in Antwerp. Some think Schyrleus de Rheita spent some time in Antwerp during the Thirty-Years War; others put him in the service of the Archbishop of Trier in Germany.

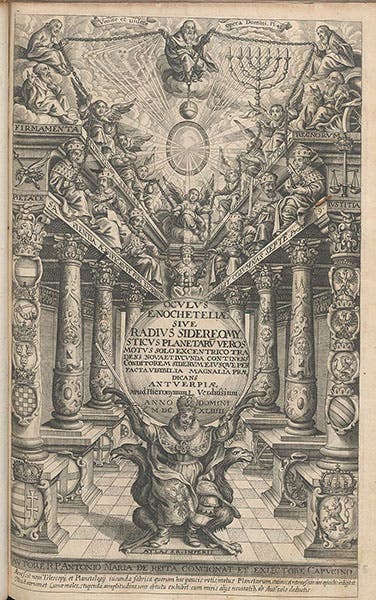

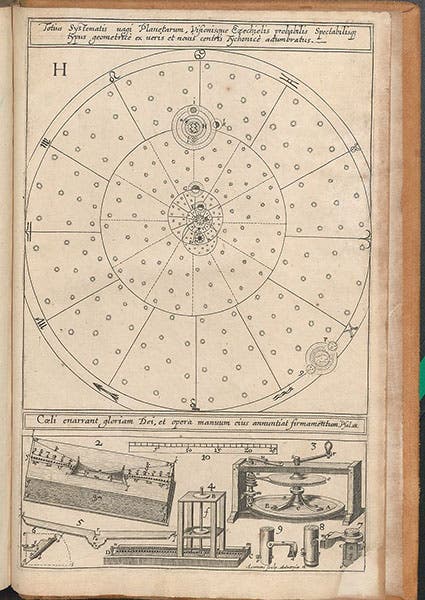

There is much about this book that is bizarre, starting with the engraved title page (third image), which shows the seven electors of the Holy Roman Empire, clinging to chains leading up the godhead, while below sits the Holy Roman Emperor himself, Ferdinand III, holding the world – or the Eye of Enoch – on his shoulders like Atlas. The book is divided into two parts; the first is dedicated to Jesus Christ and the Emperor; the second, titled “Theo-astronomia”, is dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The book has 8 engravings at the end, the last of which is the system of the world, according to the vision of Ezekiel and Tycho Brahe, with presumably the planetary epicycles being the "wheels within wheels" that Ezekiel saw in his vision.

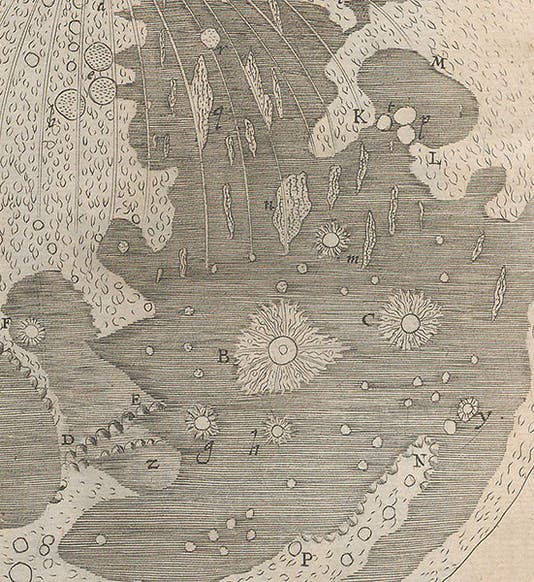

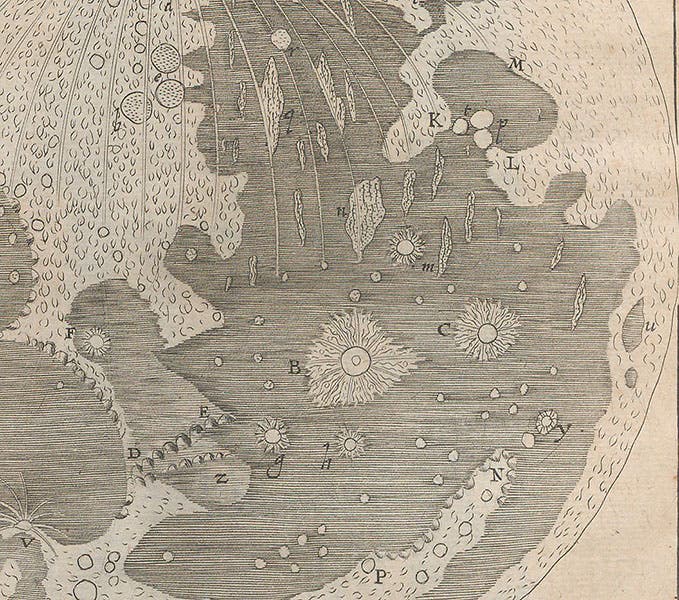

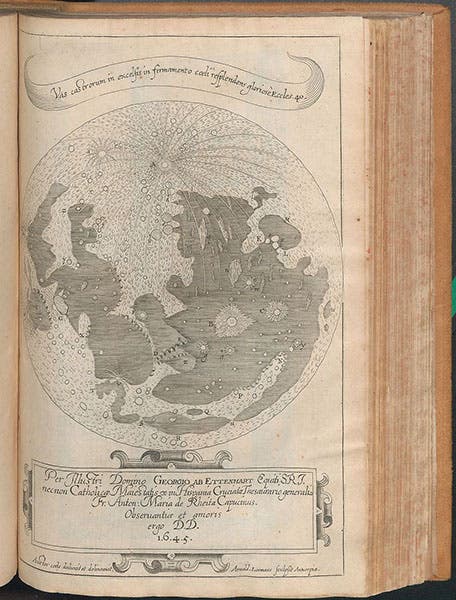

You might be excused for thinking that Schyrleus was a mystic religious figure who was unlikely to be making any contributions to the advancement of either optics or astronomy. But you would be wrong. There are several things not to sneeze at in the Oculus of Schyrleus. The first is his lunar map, which comes at the end of Part 1 (fifth image). By 1645, very few people had attempted to map the Moon, although 36 years had passed since Galileo first observed the Moon through a telescope. But Galileo did not attempt a moon map. Francesco Fontana starting drawing the Moon in 1629, but he did not publish anything until 1646, and his moon drawings would hardly qualify as maps anyway. Claude Mellan had produced three superb lunar maps in 1637, and had them engraved, but hardly anyone knew about them, so they remained exceptional. Schyrleus's lunar drawing was a map; even though it lacked a coordinate system, it had prominent craters in the proper places, labeled with indicator letters. In the detail with which we opened (first image), the craters that would later be called Copernicus and Kepler (B and C) in the Ocean of Storms are accurately positioned. And best of all, this map is absolutely original; he did not copy some other map and embellish it, because there was no other map to copy. In our exhibition of lunar maps, The Face of the Moon: Galileo to Apollo, which is more or less in chronological order, the lunar map in the Oculus batted third in the order, right after the original and the pirated editions of Galileo’s Sidereus nuncius. Schyrleus beat the more famous Selenographia of Johannes Hevelius into print by two years, and the Almagestum novum of Giambattista Riccioli (which gave us the crater names of Copernicus, Kepler, and the Ocean of Storms) by six years. Unfortunately, these two publications pretty much sent the Oculus map into permanent eclipse.

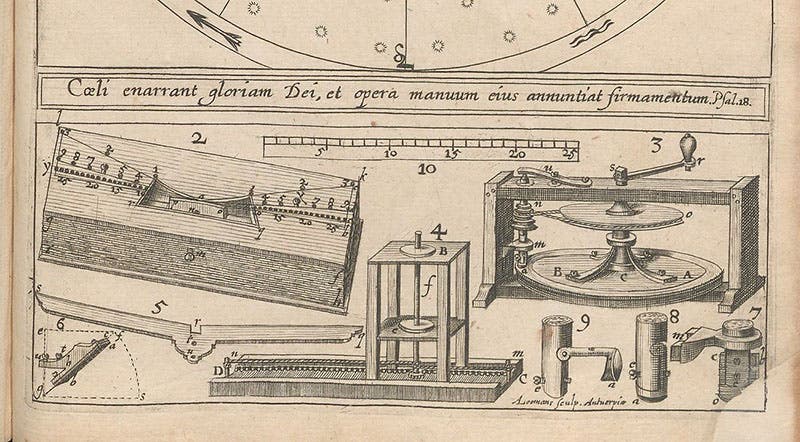

The other reason why one should not ignore the Oculus is that the section on telescope-making in Part 1 suggests how to make important improvements to the instrument. Galileo’s telescope had a convex (lens-shaped) objective, and a concave eyepiece or ocular, producing an erect image with a small field of view. Kepler invented a better, brighter telescope, using a convex ocular, but the image was inverted, so the moon seen through a Keplerian telescope was upside down (as in Schyrleus’s moon map). Schyrleus found that he could arrange three convex lenses to make a complex eyepiece that yielded an upright image in a Keplerian telescope. Three-lens oculars would become a staple for telescope-makers for the next century. And the terms objective and ocular, which we still use? Schyrleus coined them, in this book.

So the next time you want to judge a book by its cover, or its titlepage engraving, wait until you have had a look inside. There might be something there to surprise you. If you take another look at the engraving of Ezekiel’s system of the world (fourth image), you will see, at the bottom, one of the first images ever of a lens-polishing machine. I provide a detail to help you out (sixth image, below). Mysticism and science are sometimes not that far apart.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.