Scientist of the Day - Antoni van Leeuwenhoek

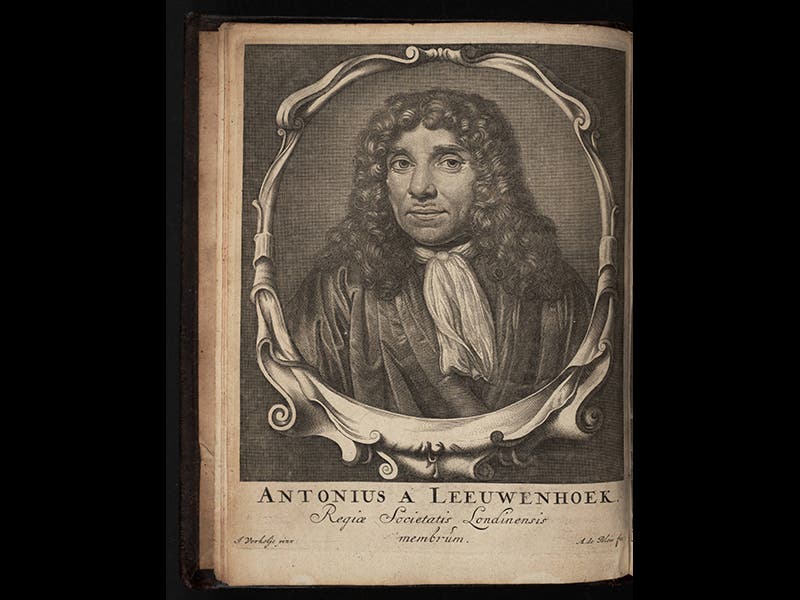

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch microscopist, was born Oct. 24, 1632, in Delft. Leeuwenhoek earned his living as a draper, an inspector of cloth, but in the 1660s he read Robert Hooke's celebrated Micrographia (1665), in which Hooke described a "simple" microscope, with one lens, before stating his preference for a multi-lens, or compound microscope. Leeuwenhoek had a go at making his own single-lens microscope, and he got so good at it that he never moved on. He looked at swamp water, blood, insects, tooth tartar, all manner of things, and sent his descriptions off to the Royal Society of London, which translated his Dutch letters into Latin or English and published them in their Philosophical Transactions for over 40 years, some 300 letters in all. At regular intervals, the letters were collected and published in both Dutch and Latin editions. We have a number of these editions in the Library, as well a several sets of the Philosophical Transactions, so we have Leeuwenhoek observations in abundance.

The Leeuwenhoek microscope is a confounding instrument (first image); it looks crude and cheap, fashioned from two flat pieces of brass not much bigger than postage stamps, with a tiny glass bead inserted between them before the brass pieces were riveted together. And yet these seemingly primitive instruments were in their time the most powerful microscopes in the world, allowing Leeuwenhoek to discover bacteria, blood cells, and spermatozoa, none of which Hooke was able to detect with his much classier compound microscope. Leeuwenhoek made some 500 instruments in his lifetime; 12 of these survive, most of them in museums in the Netherlands and Germany. The one illustrated above is the latest to be found, pulled out of a Delft canal just last year.

Leeuwenhoek's illustrations of bacteria and spermatozoa are important, but his drawings of fleas are more interesting (second image), because nearly everyone else who drew a flea made it look exactly like Hooke's flea; Leeuwenhoek was clearly his own man.

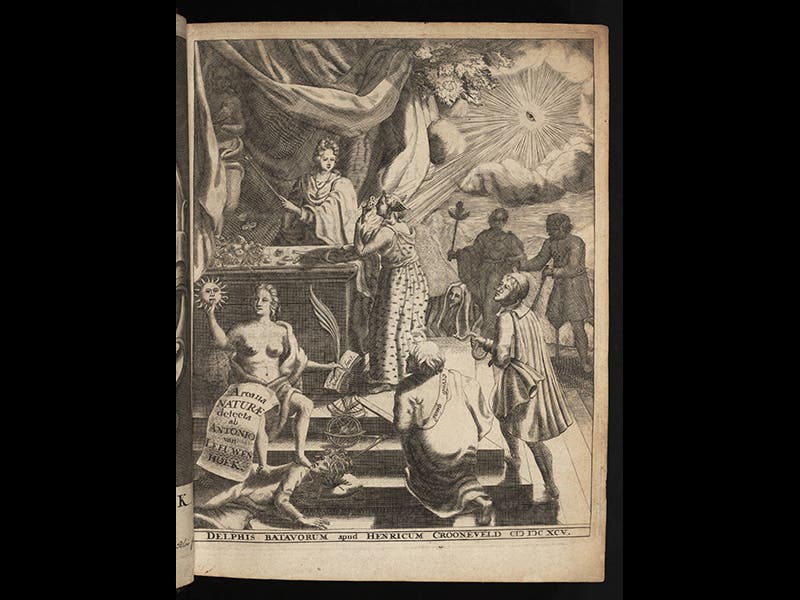

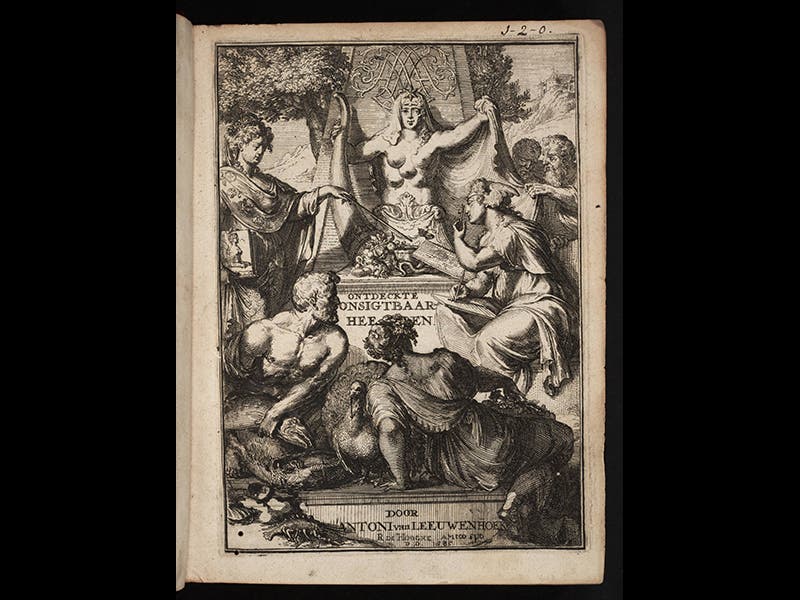

Because the tiny glass bead of a Leeuwenhoek microscope has a very short focal length, one has to hold the microscope very close to the eye for observation. Two of Leeuwenhoek’s book collections begin with allegorical frontispieces (third and fourth images), and in both of them, a personification we might call "Investigatio" is using a single-lens microscope to examine Nature (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.