Scientist of the Day - Antonio de Ulloa

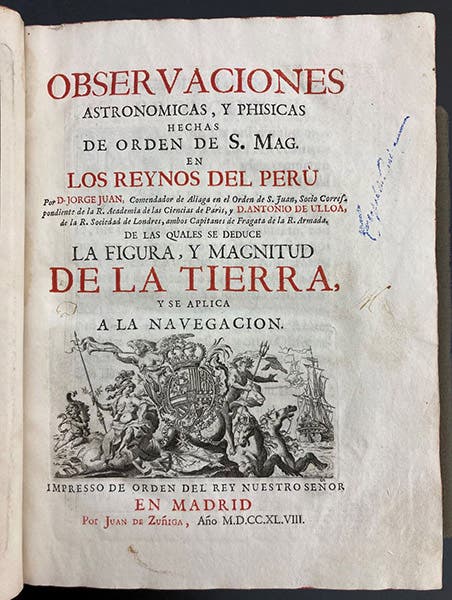

Antonio de Ulloa, a Spanish military officer, geodesist, and astronomer, died July 3, 1795, at the age of 79. Ulloa was only 19 years old and still a cadet at the naval academy in Cadiz, when he was sent, with a fellow cadet just a few years older, as the Spanish contingent of a French surveying expedition to the Vice-Royalty of Peru (modern-day Ecuador) to measure the length of a degree of latitude at the equator. His companion was Jorge Juan y Santacilia, and you can read all about the expedition, which lasted from 1735 to 1745, at our post on Juan. Since the two later co-wrote a book about their adventures, Observaciones astronomicas, y phisicas: hechas de orden de S. Mag. en los reynos del Peru (1748; third image), it is hard to tell the two apart; nearly everything we said about Juan could also be said of Ulloa, and we do not really need to say it again. So please read the post on Jorge Juan y Santacilia.

Differences between the two men first emerge on their voyages home to Spain. Juan and Ulloa decided to return on separate ships, reducing the likelihood that all their work might be lost in a single shipwreck. Juan made it home without mishap in 1745, but Ulloa's ship was captured by the British, and Ulloa was imprisoned and sent back to London. Fortunately, members of the Royal Society found out that there was a member of the French equatorial expedition in their midst, and the President, Martin Folkes, pulled strings to secure Ulloa’s release and the return of all his records and collections. So Ulloa eventually got back to Spain, a year late, and he and Juan were able to write and publish their book in 1748.

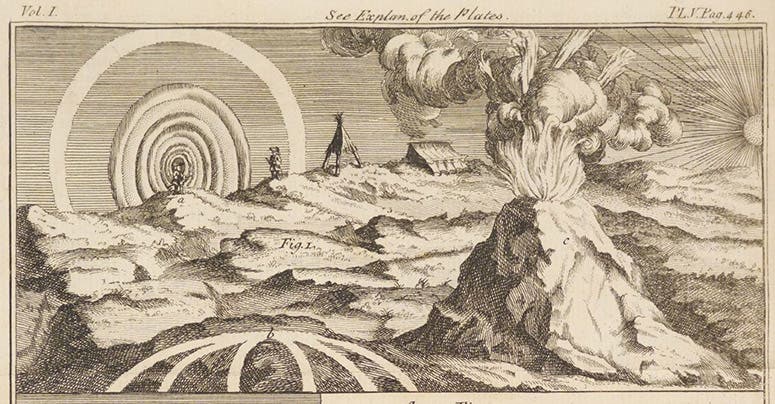

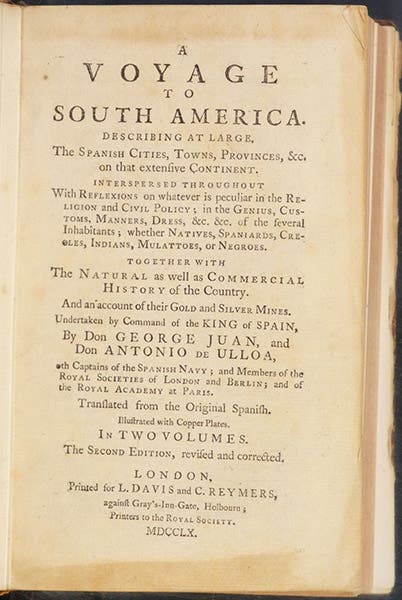

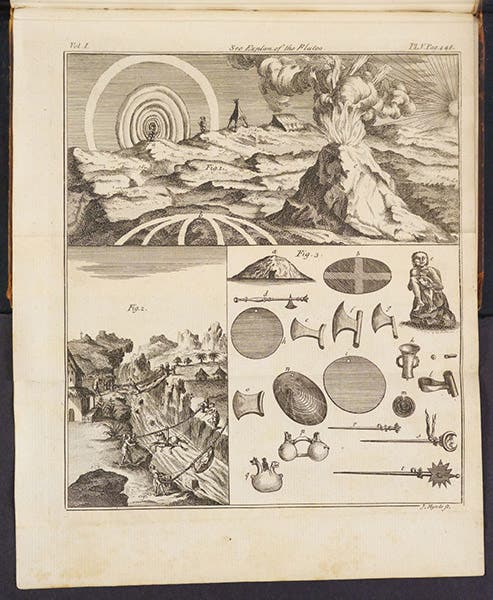

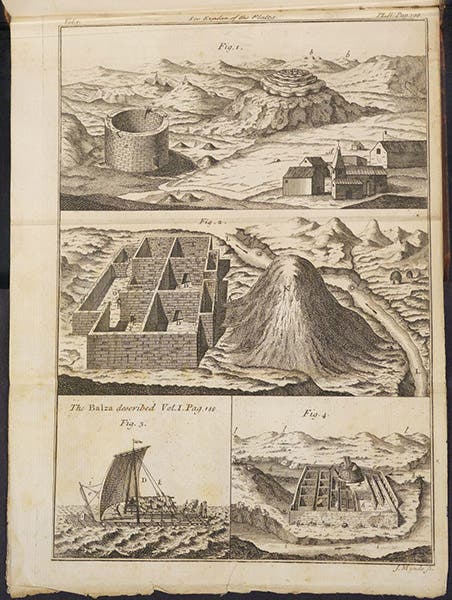

However, we have another book in our collections about Ulloa and Juan in South American, A Voyage to South America, which is a second edition (1760) of a translation of a Spanish account, Relacion historica del Viege a la America Meridional (1748), stated to be the work of both Juan and Ulloa, but apparently mostly by Ulloa (fourth image). We do not have the original Spanish edition of the Relacion, just the translation. It is different from the first book in that it is unconcerned with the geodetic work, and very much concerned with the natives and their activities and occupations, especially the mining of gold and silver, and the planting of opuntia (prickly pear) and the harvesting of cochineal, the red dye so much in demand in Europe. Ulloa also reported on odd physical phenomena, such as halos seen around shadows at the high altitudes around Quito. One plate depicts the halos and tosses in an eruption of Cotopaxi for good measure, as well as some of the Incan tools and relics found in Peru, and a view of the tarabitas or rope trams that are used to cross deep gorges in Peru. We show a detail of that plate as our lead image, and the complete plate just below (fifth image). Another folding plate depicts some Incan ruins (sixth image).

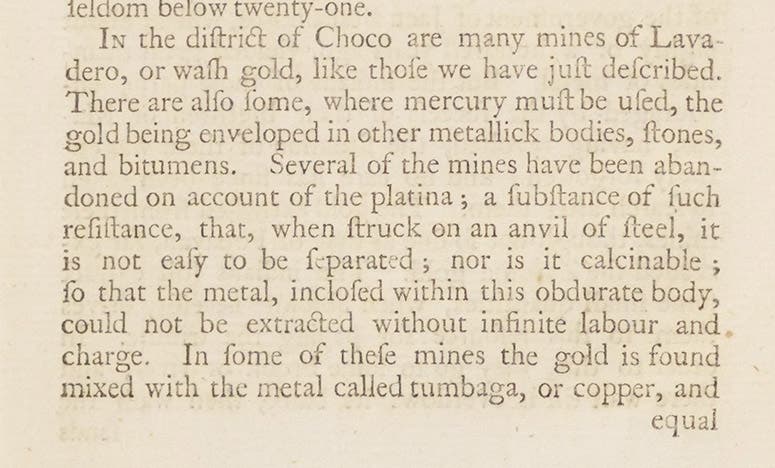

In his discussion of the gold and silver mines, Ulloa mentions a very hard substance that can clog up mining operations, and which he calls platina, “little silver.” This is one of the first mentions of platinum, and Ulloa is sometimes credited with the discovery of platinum. We show here a paragraph from the 1760 translation in which platina is mentioned and discussed (seventh image).

Ulloa spent the rest of his career as administrator of various Spanish territories in South America, including Louisiana, when the French ceded it to Spain. But Ulloa was not filled with the spirit of tact and diplomacy, and he usually aroused the hostility of the local citizens within a few years, so that he was often removed from office and sent on to another region, where the process was repeated. But in his defense, Ulloa never wanted a political life; he loved natural history and astronomy, and it is too bad, for his sake and ours, that he was not often allowed to pursue it.

Ulloa was promoted to Vice Admiral before he retired, and there are some monuments and plaques honoring Ulloa in Seville. There was a posthumous portrait painted in the 19th century that is quite nice (second image), and it was the basis for a postage stamp, issued by Spain in 2016, the 300th anniversary of Ulloa’s birth (last image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.