Scientist of the Day - Antonio Pigafetta

Antonio Pigafetta, a Ventetian writer and adventurer, set sail on Sep. 20, 1519, on board the Trinidad, on what would turn out to be the first circumnavigation of the globe. The captain of the Trinidad was Fernão de Magalhães, a Portuguese navigator known to English speakers as Ferdinand Magellan. Although Portuguese, Magellan was sailing under the flag and patronage of the King of Spain. The purpose was to find a new western route to the Spice Islands. Pigafetta was on board as a supernumerary, just along for the ride. He intended to write and publish an account of his adventures.

We told Magellan's part of the story in a post on Magellan. After making it through the straits of Magellan (while losing two of his five ships, on to shipwreck and on to desertion), and discovering and crossing the Pacific Ocean (a sail of 110 days), they finally encountered the Isles of Thieves (Guam and the Marianas) and then the Philippines, where Magellan was killed in a skirmish on the island of Mactan. Down to two ships, and captained by Juan Elcano, the remainder of the crew, including Pigafetta, finally made it to the Spice Islands, or the Moluccas, where they loaded up with cloves and nutmeg. They loaded one ship so heavily that it burst at the seams, so Elcano took the one remaining ship, the Victoria, and the remnant of the crew (including Pigafetta), across the Indian Ocean, around Africa, and back to Spain, returning home on Sep. 8, 1522, almost three years from the day they left. The crew was down to 18 (still including Pigafetta), out of the 240-odd men who left in 1519. We told this last half of the story in a post on Elcano.

![“Hereafter are figured the islands of Zzubu, Mattan,and Bohol [the Philippines]”; Mattan (Mactan) has the additional legend: “Here died the captain general” [Magellan], watercolor in Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, by Antonio Pigafetta, French translation, Beinecke MS 351, fol. 53 verso (collections.library.yale.edu)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/c29d7b12-53a3-47dd-bcfb-d9e5cc35ee1f/pigafetta3.JPG?w=433&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

“Hereafter are figured the islands of Zzubu, Mattan,and Bohol [the Philippines]”; Mattan (Mactan) has the additional legend: “Here died the captain general” [Magellan], watercolor in Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, by Antonio Pigafetta, French translation, Beinecke MS 351, fol. 53 verso (collections.library.yale.edu)

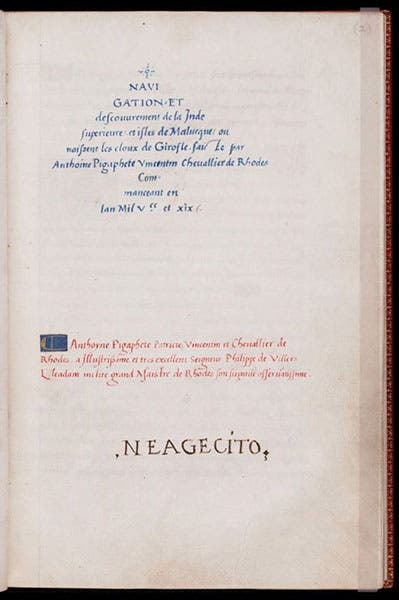

So now to Pigafetta. He was there for every event, including the death of Magellan, where he was wounded, and he kept a diary, with daily entries, three years’ worth. He also made charming drawings, often called maps, although they really just impressions, of the places they visited. From this diary, Pigafetta compiled a narrative, which he distributed freely to the likes of Emperor Charles V (Charles I of Spain) and the Doge of Venice. All the official records, including the logs of the officers, went into the secret archives of Spain, and they have never emerged and are presumed lost. So Pigafetta's account is the only one we have of this incredible saga, probably the most significant voyage of the entire 16th century. He called it: Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo (Report on the First Voyage Around the World).

Elcano seems to have made quite a few copies of his narrative for distribution to would-be patrons, but none of those survive, and none were printed. In the 1790s, a manuscript was found in Milan, and this gave rise to three translations into French. These four manuscripts are the only 4 that survive of Pigafetta's account. One of the French translations is in the Beinecke Library at Yale University, and it is said to be the finest of all, not only because the script and paper are lovely, but because it contains 23 watercolor copies of the drawings of Pigafetta. We have used four of those paintings to illustrate our post today. We used three to decorate our post on Magellan, with one being re-used for this post.

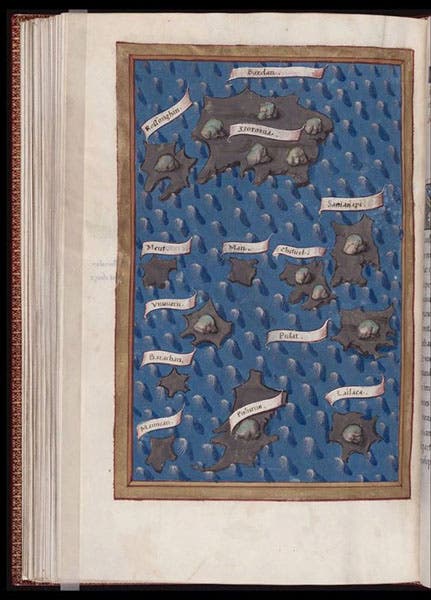

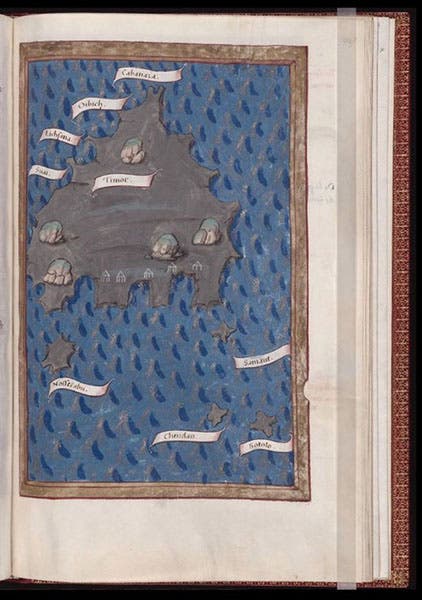

The drawings we include here show the island of Mactan in the Philippines, where Magellan was killed (his death noted in a little banderole) (third image); the Moluccas (the Spice Islands), including a clove tree (first image); Bandan, whose twelve islands provide nutmeg and mace (fourth image; Pigafetta tells us that only 6 of the islands provide mace and nutmeg; whether he knows that the two spices come from the same nut, I couldn’t tell); and the island of Timor, which they encountered just before heading home (fifth image).

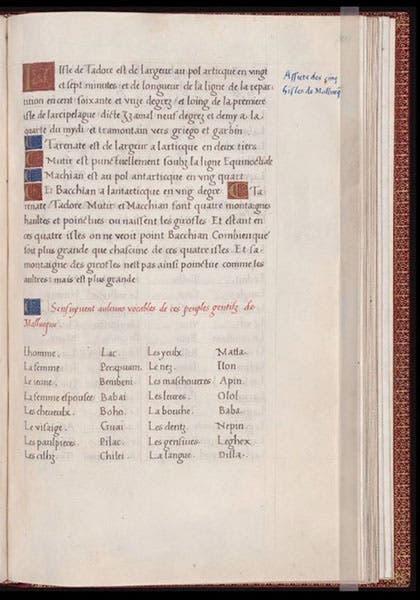

Pigafetta also made serious attempts to understand and record in his diary the languages of the peoples they encountered. He included pages of vocabulary from half-a-dozen languages in his Relazione. We show here the first page of a vocabulary for the natives of the Moluccas, where we learn that the Moluccan word for “the man” is “Lac,” while that for “rice” is “Bughaz” or “Baras” (sixth image). At the end he even has their words for the numbers one to ten (not shown on this page.)

I have never seen the original Beineke Pigafetta manuscript, known as Beinecke MS 351, and I have no excuse, since I grew up not 60 miles away. Fortunately, the Beinecke has made the entire manuscript available online. And before online facsimiles were possible, in 1969, Yale University Press published a two-volume set titled Magellan’s Voyage: A Narrative Account of the First Circumnavigation. The first volume is a translation of Beinecke MS 351. And the second is a facsimile reproduction of the original manuscript, in full color. Our Library has this set.

We have no real portrait of Pigafetta – it is a pity he never attempted a self-portrait. But we do have a statue, erected in his honor in Vicenza (sixth image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Five of the islands where grow the cloves [Moluccas],” watercolor in Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, by Antonio Pigafetta, French translation, Beinecke MS 351, fol. 85 verso (collections.library.yale.edu)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/e4518cca-321f-4ae4-bb99-321fdfbc2c79/pigafetta1.JPG?w=433&h=472&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![“Five of the islands where grow the cloves [Moluccas],” watercolor in Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, by Antonio Pigafetta, French translation, Beinecke MS 351, fol. 85 verso (collections.library.yale.edu)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/645d76e5-a6c5-464e-89a9-3e0d5b709f5d/pigafetta1.JPG?w=433&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)