Scientist of the Day - Archimedes of Syracuse

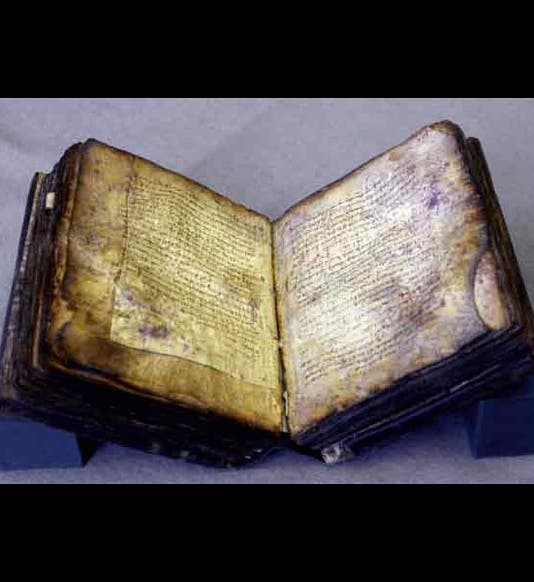

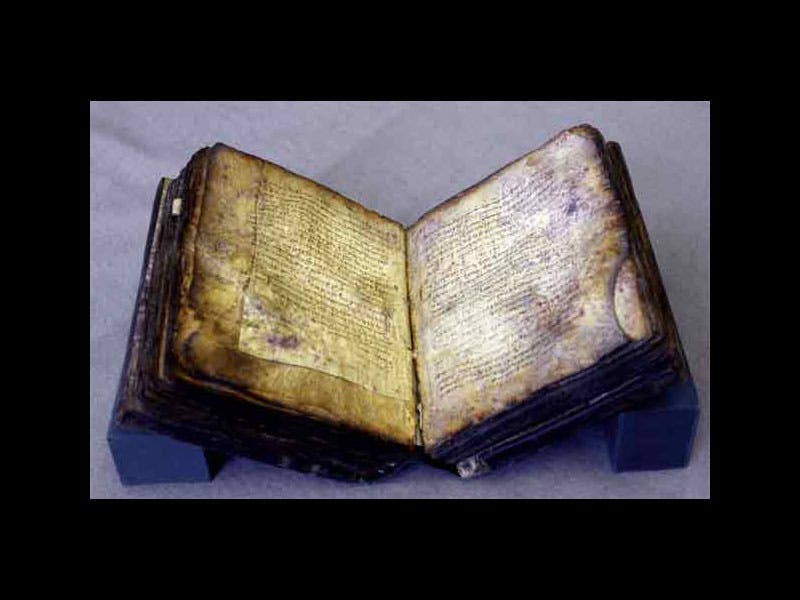

On Oct. 29, 1998, the gavel came down at the auction of an ugly-looking medieval manuscript (first image above). Splotched with mildew, displaying a Greek prayer book of no special interest, the codex appeared to have little going for it except its age, which was 13th century. But one important feature had brought bidders from around the globe and on the phone to Christie’s in New York: the manuscript was a palimpsest, which means the parchment had been scraped and reused, and there was another text, several centuries older and only faintly visible, lying under the prayer text. That "other text" proved to be a collection of seven of the works of Archimedes, in Greek, including a treatise, "The Method," for which no other copy exists.

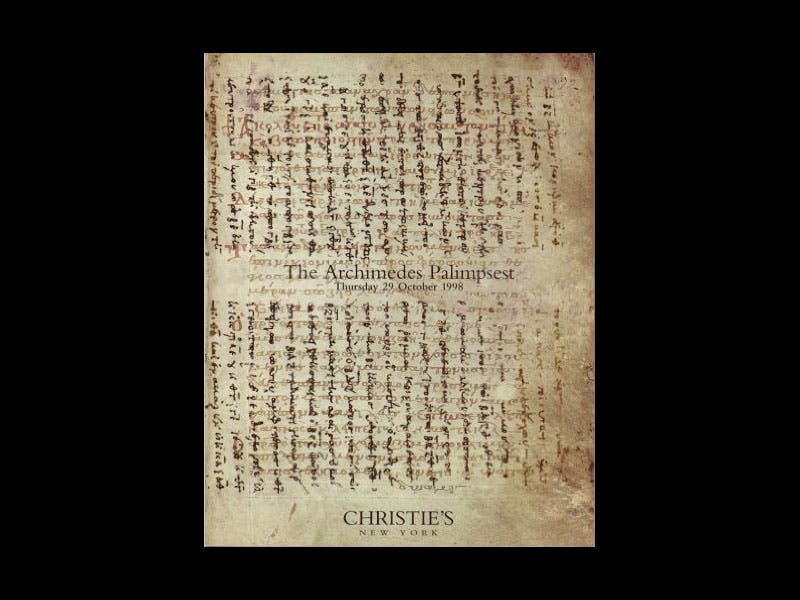

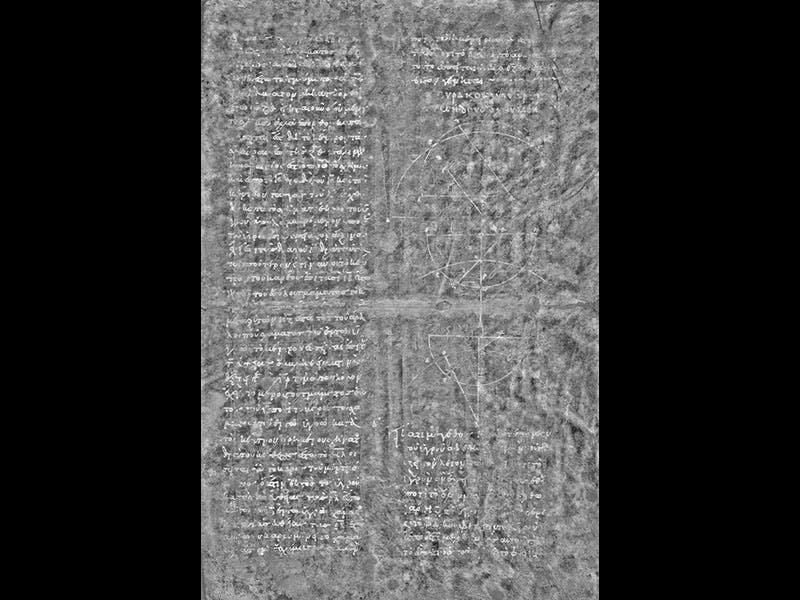

The Archimedes palimpsest first came to light in 1906, when Johan Heiberg, a scholar of ancient Greek mathematics, had examined it in Constantinople and recognized the underlying script as Archimedean. The manuscript subsequently turned up in the library of a French collector, then disappeared for 75 years, and then emerged again in 1998, when Christie’s offered it up at auction (second image). When the gavel dropped, the winning bid was an even $2 million (with another $200,000 in premiums added on top). The buyer remains anonymous (although it is a not-very-well-kept secret in the rare book world), but the new owner immediately consigned the palimpsest to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, where a large team of scholars, armed with state-of-the-art digital photographic equipment and sophisticated analytic software, have been teasing out the hidden text for about 15 years now (third image, where the underlying Archimedes text now stands out). It has been called the most advanced imaging project in the world, and there have been several popular books on the project written by the investigators. The Walters has placed a number of short informative videos concerning the palimpsest on Vimeo, including one that quickly leafs through part of the manuscript.

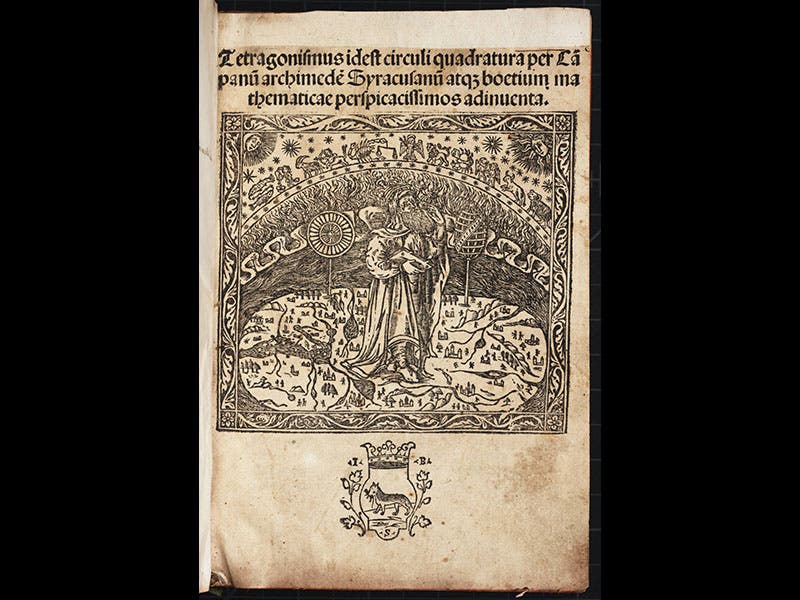

No one has any idea what Archimedes looked like, as there are no portrait busts from his time. We are partial to a title-page woodcut that appeared on one of the earliest printings of an Archimedes tract, the Tetragonismus (1503), which is part of our History of Science Collection (fourth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.