Scientist of the Day - Arnout Vosmaer

Arnout Vosmaer, a Dutch naturalist, was born Sep. 23, 1720. In 1756, Vosmaer became director of the natural history cabinet of Prince William V of Orange. Since William was only 8 years old at the time, Vosmaer came by his appointment through William’s Governess, Anne of Hanover, widow of William IV, who was an ardent collector of animals, alive and dead, and of natural history artifacts. She learned about Vosmaer when he was an active bidder at the auction of the properties of the great collector Albertus Seba in 1752. Princess Anne was apparently impressed with Vosmaer's choices of specimens; not only did she hire Vosmaer, she also bought his entire collection for William.

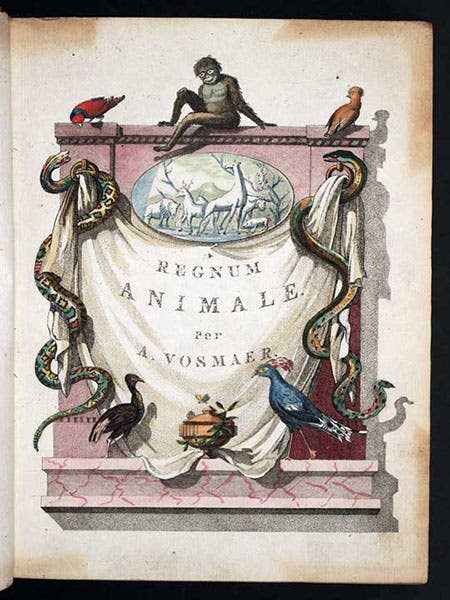

Vosmaer ended up supervising both the cabinet (the museum) and the menagerie that had been started by William IV and continued by his wife Anne. Starting in 1767, Vosmaer began issuing fascicles describing exotic animals and birds in the menagerie, accompanying the description with an engraving executed by a notable Dutch artist, such as Aert Schouman.(who did most of the birds). Vosmaer died in 1799; after his death, 33 of these brochures, each of which had its own titlepage, were bound up in a volume with a new title page: Description d'un receuil exquis d'animaux rares (1804). The volume also has an added engraved (and colored) titlepage, with the title Regnum animale, which is often used to refer to the book, although it is not its true title (second image).

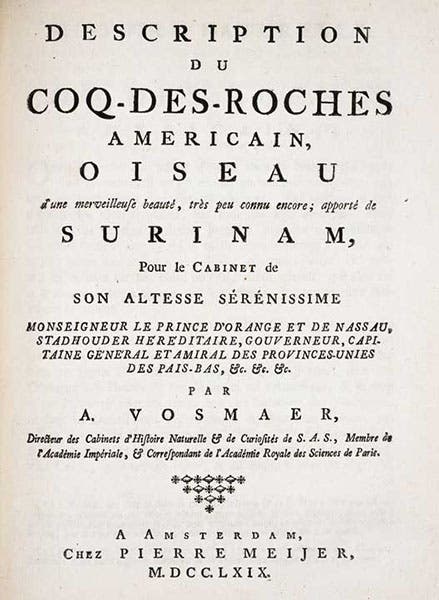

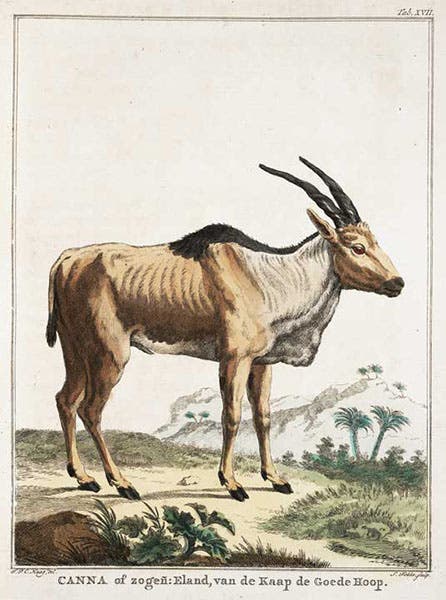

Vosmaer's book is the subject of the rest of our essay, and we will mostly allow the engravings to speak for themselves. They are colorful and attractive, and depict animals and birds that were not commonly portrayed in the usual natural history encyclopedias of the day. We begin with the cock-of-the-rock, a beautiful bird that had been brought to the menagerie at Voorborg from Surinam. Our first image is a slight close-up of the actual engraving. We show also the individual titlepage for the cock-of-the-rock fascicle; there are 33 of these, all different, in the volume (third image). The eland (fourth image) is one of at least three African antelopes in William V’s zoo (we showed the kudu (as well as the cock-of-the-rock) in our 2009 exhibition, The Grandeur of Life). The kingfisher (fifth image) came from Guiana, and the secretary bird (sixth image) from South Africa. All of these were alive at the time of portrayal; when they died, as exotic animals tend to do in captivity, they were stuffed and transferred to the cabinet.

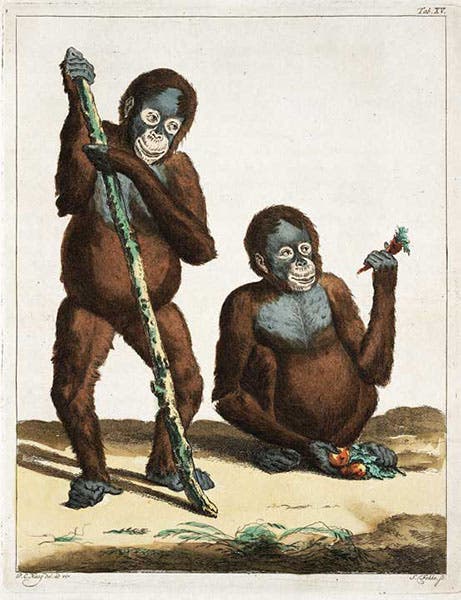

Vosmaer's one small claim to fame in zoology was in arguing that the primate often referred to as the "orangutan" by naturalists such as Buffon was not an orangutan at all, but rather an African ape (the chimpanzee). The true orangutan was native to the Dutch East Indies and was quite different from the chimpanzee. His publication on the orangutan included two engravings of juvenile orangs that William V had imported from Borneo. These are in fact the first printed images of real orangutans anywhere. We included one of them in the Grandeur of Life exhibition, and we display the other one here (seventh image).

Except for what the book tells us, we don't know much about Vosmaer. English naturalist Thomas Pennant visited William’s cabinet and was not impressed with its director, calling Vosmaer a "frenchified Dutchman, extremely ignorant." Vosmaer was far from ignorant, so Pennant may have been a bit jealous of the cabinet and the position Vosmaer occupied. As for portraits of Vosmaer, there is a portrait relief by Henry Fuseli, supposedly of Vosmaer, that one can find online in the inventory of an art reproduction vendor, but nowhere else. Until I can find that portrait authenticated by an authoritative website, which I doubt will happen, we will leave Vosmaer faceless.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.