Scientist of the Day - Ashton Lever and Sarah Stone

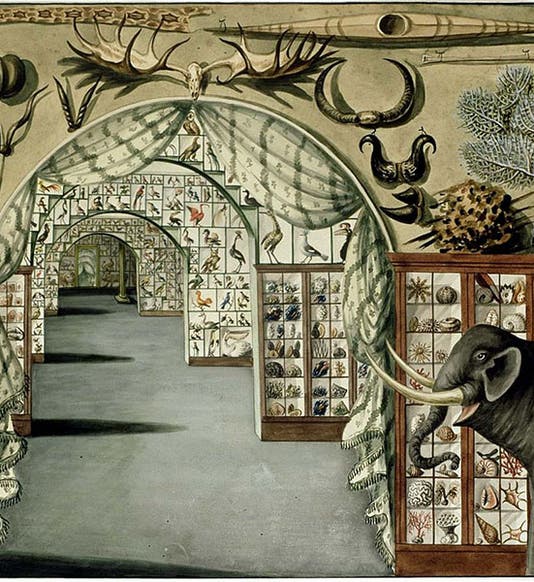

Ashton Lever, an English collector, was born Mar. 5, 1729. In 1760, Lever bought a large collection of shells and was hooked on collecting; indeed, he was on his way to becoming the most acquisitive collector of natural history objects in the British Isles. In 1772, he opened a museum at his estate near Manchester, and 2 years later he moved to London and installed his collection in a house on Leicester Square. It was called the Holophusicon ("encompassing all of nature:), which I am sure brought viewers in off the streets in droves. The museum contained some 25,000 exhibits, and we have a contemporary painting of the interior, made by a woman, Sarah Stone, about whom we will say more shortly (first image). The museum was open to the public, and even though he charged a small admission fee, Lever spent far more than he took in and eventually went broke, and he had to sell his entire collection in a lottery in 1786. He died 2 years later. The winner of the lottery, James Parkinson, kept the museum intact for 20 years, and then he sold it at auction in 1806, and the collection was dispersed, most of the buyers being individual collectors themselves or representatives of foreign museums.

Sarah Stone was born around 1760, we don't know exactly when. Her father was a fan painter, and Sarah showed considerable artistic talent at a young age. She was only in her mid-teens when Ashton Lever noticed her natural history paintings and commissioned her to sketch the items in his collection. These watercolors soon numbered in the hundreds and then the thousands, so that eventually several rooms of the Leverian Museum were devoted to displaying her work.

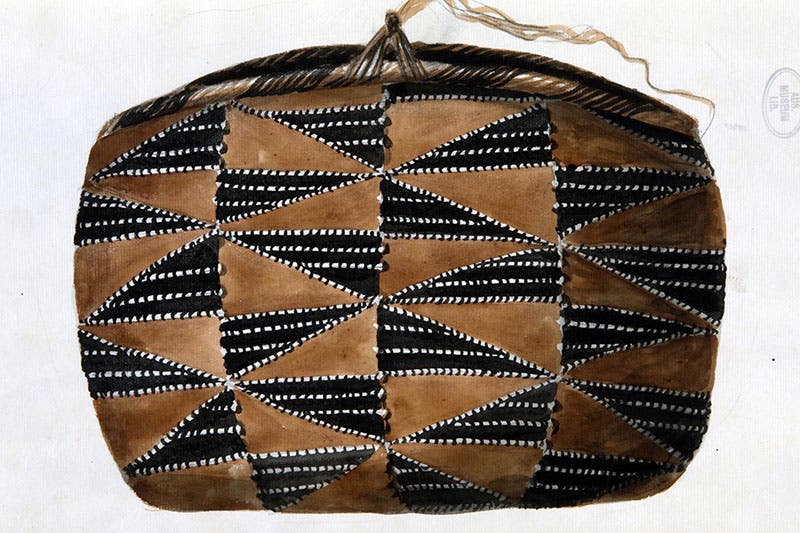

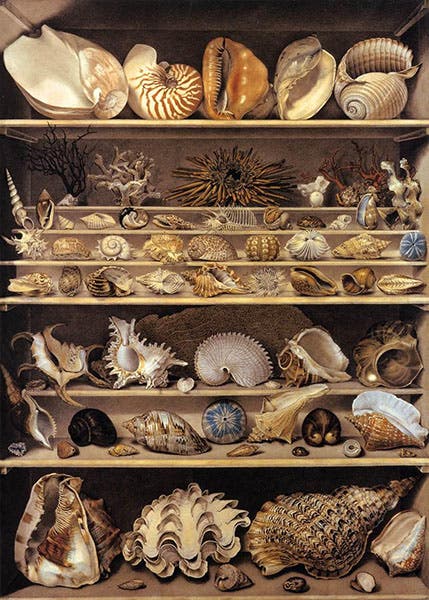

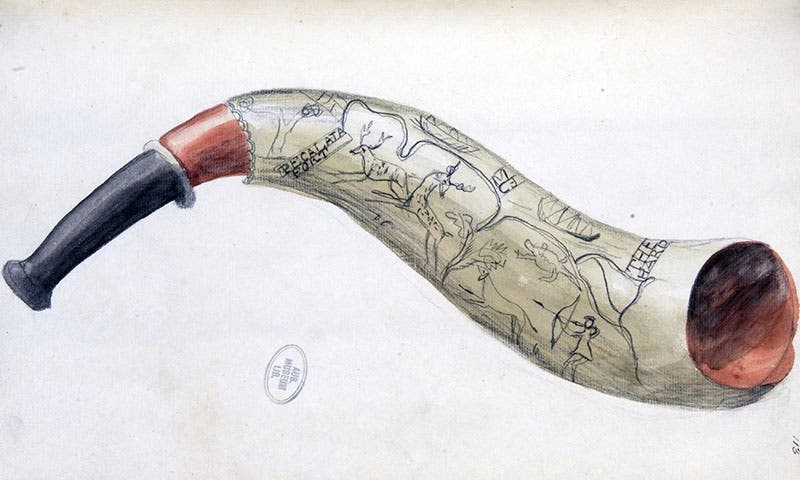

Fortunately, over 900 of these drawings still survive. Some of them were later bound up into albums, 6 of which are in various collections: one in the Natural History Museum of London (almost entirely birds; see second image), one in the Australian Museum in Sydney, three in the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, and one in the State Library of New South Wales. The prevalence of Stone drawings in Pacific collections is the result of the fact that many of her drawings show ethnographic items brought back from Captain Cook's second and third voyages, objects such as baskets from Tonga (third image above) and feathered idols from Hawaii.

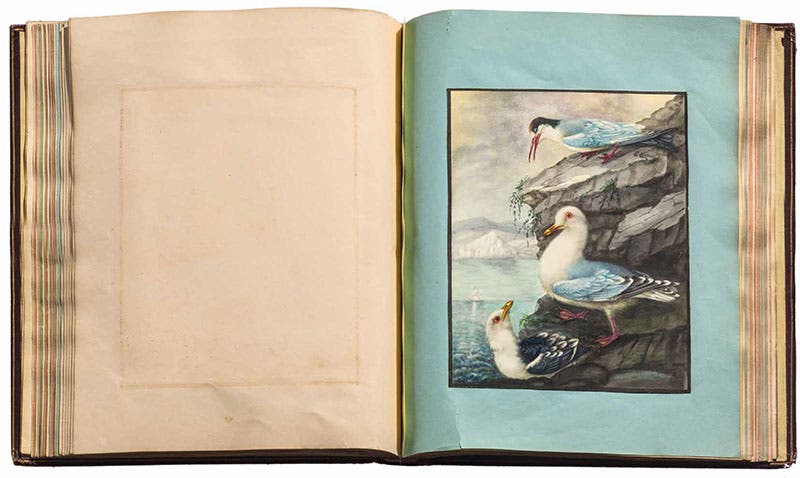

After Lever died, Stone kept painting, and her later works, which are often compositions rather than pictorial records, show that she developed into an exceptional artist. This painting of shelves of shells, which apparently is in the Natural History Museum (although you wouldn’t know it from their website), is extraordinary (fourth image just above). A small album of hers with 40 watercolors (now the 7th known) recently surfaced and is on the market – these were painted after she married a mariner and became Mrs. Smith – and they are lovely as well (fifth image just below).

Sarah Stone had an impressive reputation in early 19th-century England – to have a painting of yours compared to one of hers was high praise indeed. But her last known painting was the year of the auction – 1806 – and although she lived for 38 more years, we do not know much about her life after the dispersal of the Museum. We hope she enjoyed some fruit from the high esteem in which she was held by other natural history artists.

There is an excellent book on Sarah Stone by Christine E. Jackson, Sarah Stone: Natural Curiosities from the New Worlds (1998). This is a large quarto with many illustrations. Even more impressive is Holophusicon, the Leverian Museum: An Eighteenth-Century English Institution of Science, Curiosity, and Art (2011), by Adrienne L. Kaeppler. Ms Kaeppler, using the auction sale catalogs, has identified nearly all of the items in the Leverian Museum, and, over the course of 40 years, actually managed to locate many of them in present collections. The drawings of Sarah Stone, especially those of the ethnographic items, were indispensable in identifying the items in museum collections. This book, also a large quarto, has many hundreds of illustrations and is as impressive a piece of scholarship as one is likely to find. Both books are available in the Library’s general collections.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.