Scientist of the Day - Charles Mason

Charles Mason, an English astronomer, died Oct. 25, 1786, at about age 58. Mason was born in Gloucestershire in western England, and we know little about his upbringing. He must have had some training in astronomy, for he shows up as an astronomer at Greenwich Observatory about 1756. And he must have done well at Greenwich, for he was one of those chosen by the Royal Society to make a journey partway around the globe to observe the transit of Venus of 1761, in order to better determine the distance from the Earth to the Sun. His travelling companion was a surveyor, Jeremiah Dixon, a “Geordie boy” from the north country.

Mason and Dixon planned to go to Sumatra, but they got no further than South Africa, as they realized they would never make it to the East Indies in time, so they observed the transit from there. Their observations were so professional and accurate that when, shortly thereafter, several governors in the British colonies asked the Royal Society for help surveying their colonial boundaries, Mason and Dixon were offered up for the job. They traveled to Philadelphia in 1763, and over the course of four years, surveyed the dividing lines between Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia (then including West Virginia as well).

It may seem odd that the families of William Penn and Lord Baltimore (Frederick Calvert) would send all the way to England for surveyors, but the fact is that colonial surveyors were not well trained and had poor equipment. Mason and Dixon brought with them a zenith sector and a transit instrument, both made by John Bird, a noted London instrument maker. Mason also had the astronomical skills necessary to lay out an accurate line of latitude.

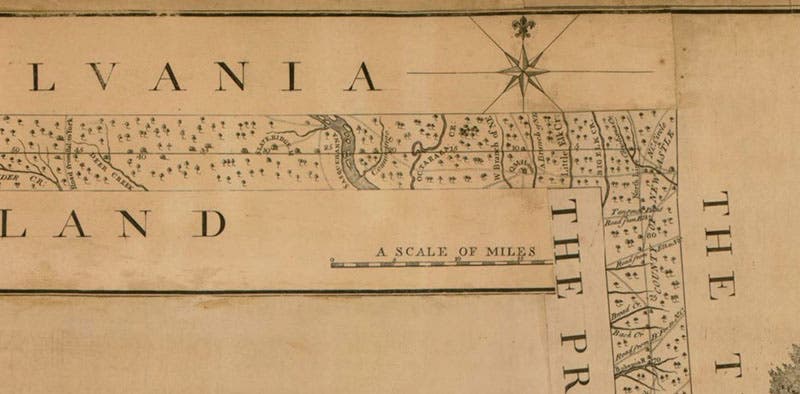

Mason and Dixon started at a point 15 miles south of Philadelphia’s southernmost point (second image) and worked their way west, establishing a line at 39° 43’ 20” North latitude. The line was marked every mile by a milestone. Amazingly, the stones were made in England and shipped all the way to Philadelphia. Since each milestone weighed hundreds of pounds, that was no easy feat. Each milestone was carved with an “M” on one side and a “P” on the other; perhaps it was easier to get the carving done back home. Every 5 miles there was a “crown stone”, taller than a milestone and carved with the coats of arms of the Penn family on one side and the Calvert family on the other (third image). This more elaborate carving would surely have been more easily done in England.

Mason and Dixon worked to establish their line for 4 years, from 1763-1767, before they were turned back by hostile Indians. The line west was extended to 233 miles from its origin. Mason and Dixon laid 132 stones themselves, many which are still in place, although most have been reset. Every now and then, one is dug up in a farmer’s field and added to the list. Some, especially the crown stones, have now been protected by iron cages (third image).

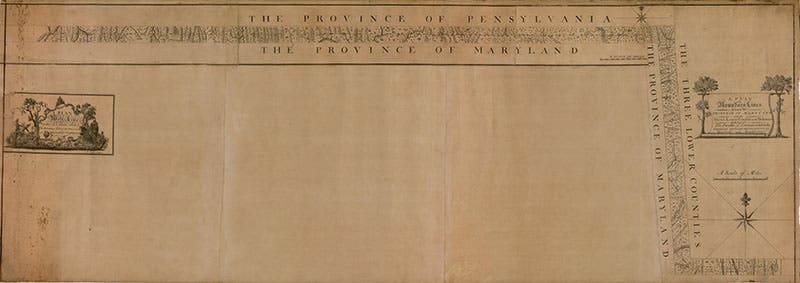

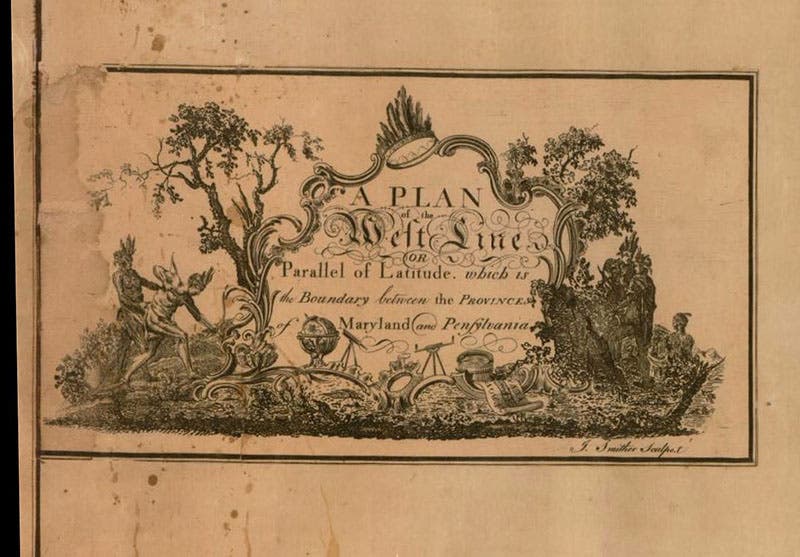

In 1768, a map was published showing the complete Mason-Dixon line, both the east-west part between Pennsylvania and Maryland, and the shorter north-south portion between Maryland and what would become Delaware (fourth image). The map (which must be 6 feet long) is very strange, since most of it is blank, with only the east-west line at the top, and the north-south line at the right, filled in. I don’t know who officially authorized the map; the copy I looked at (from afar) is in the Library of Congress. According to the LoC, Mason drew the map. We show the complete map; a detail of the upper right, where the line makes its right angle turn to the south (fifth image); and the legend at far left, which, you will note, makes no mention of Mason or Dixon (sixth image).

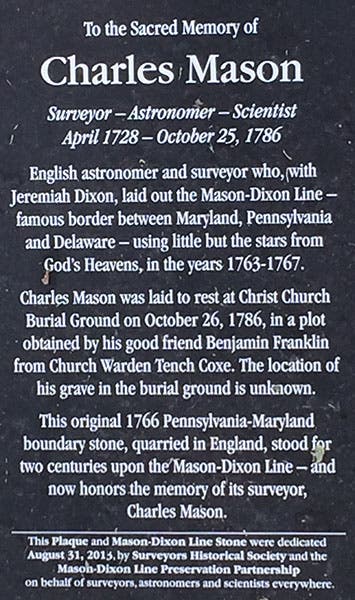

The Mason-Dixon line would not acquire its modern meaning (and fame) until the Missouri Compromise of 1820 interpreted the line as a boundary between North and South, between free states and slave states. It wasn’t even called the Mason-Dixon line until then. Mason went back to England in 1768, unaware that he would one day be half of a household name, and he spent some years trying to claim a portion of the Longitude Prize money for his lunar method of determining longitude (and was ultimately awarded some £750). For reasons unknown, Mason returned to Philadelphia, now part of the United States, in 1786, with his wife and large family, only to die a month after his arrival. He was buried in the churchyard of Christ Church, Philadelphia, supposedly in a plot secured by Benjamin Franklin, but the location of his grave is not known. In 2013, a milestone from the Mason-Dixon line was installed there as a quasi-gravestone, and a plaque put in place to explain it (seventh and eighth images). These will have to do as memorials (along with the milestones), since we have no portrait of either Mason or Dixon.

Mason and Dixon were the subject of a song by the renowned rock guitarist Mark Knopfler (formerly of Dire Straits), who released "Sailing to Philadelphia" in 2000. The song is a duet between Mason and Dixon, with Knopfler singing the part of Dixon, who (in the song) is optimistic about the promise of the American West, and the venerable James Taylor voicing the concerns of Charles Mason, “a baker's boy from the west country who joined the Royal Society,” who thinks the West promises nothing but danger and death (we actually have no idea at all what Mason or Dixon actually thought about westward expansion). You can listen to “Sailing to Philadelphia” here on YouTube. It is a good song, but short of Knopfler's best, such as “Sultans of Swing”. However, historians of science cannot be too choosy when it comes to songs about historical scientists – we will take what we can get. And if you don’t know “Sultans of Swing,” or haven’t heard it in a while, check out here a young Knopfler, circa 1980, with an unbelievable command of his 1961 Fender Stratocaster. To get back to our subject, a much older Mark Knopfler made a 10-minute video about Mason and Dixon, which is actually quite nice, and which you may view here. It has additional views of the stones, the map, and the archives of the Royal Society.

We wrote, long ago, a post on Jeremiah Dixon, with different images (except for the map), which is available here. There is an organization, the Mason and Dixon Line Preservation Partnership, which since 1990 has been helping locate and preserve the milestones, and which maintains a website with lots of information, and many, many photos of individual stones.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.