Scientist of the Day - Christophe Plantin

Christophe Plantin, a French printer, died July 1, 1589, at the age of about 69. Plantin is sometimes referred to as a humanist printer, but he wasn't really, at least not to the extent that predecessors like Johann Froben and Johannes Oporinus were scholars as well as printers. Plantin was simply a very good printer and an excellent businessman, who founded a press, the Plantin Press, or Officina Plantiniana, that was influential not only in his own lifetime, but for the next 300 years. People collect Elzevir imprints, and Plantin imprints, and that's about it for Renaissance and early modern collectible printers.

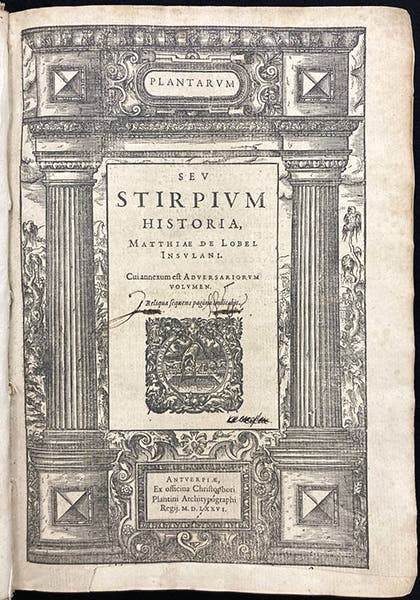

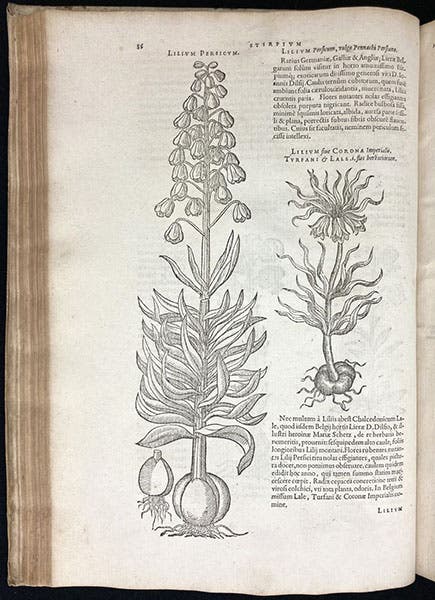

Plantin printed Bibles – the famous Polyglot Bible was his handiwork – and other liturgical material, and emblem books, none of which we collect. But he also published some scientific works, most notably the Theatrum orbis terrarum, or world atlas, of Abraham Ortelius (1570), with its beautiful hand-colored engraved maps. We have a 1592 edition, issued just after Plantin's death; you can see some images at our post on Ortelius. Plantin also published herbals, by renowned botanists such as Carolus Clusius, Rembert Dodoens, and Matthias de L'Obel, each of which has many hundreds of woodcuts. We show the title page of the Plantin imprint of Plantarum sev stirpium historia, by Matthias de L’Obel (1576; third image), as well as a sample page, this one showing woodcuts of a Persian lily and a crown imperial (fourth image)

Plantin established his press in Antwerp, and then when the Spanish destroyed that city, he moved to Paris, then to Leiden, and finally back to Antwerp, keeping the Leiden press open as well. He married and had 5 daughters who were involved in the business. One married Jan Moretus, who started working for Plantin as a printer’s apprentice, and who, with his wife, took over the Antwerp press after Christophe's death. Jan’s son Balthasar inherited the press after Jan died in 1610, and the Plantin-Moretus Press continued to issue significant scientific books, such as the beautiful Opticorum of Francois Aguilon, published in Antwerp in 1613, with its lovely headpieces, engraved after drawings by Peter Paul Rubens. You can see some of these at our post on Aguilon, as well as our post on Rubens.

Plantin designed a printer’s mark that is nearly as famous as the dolphin and anchor of Elzevir. It shows a drafting compass being used to draw a circle, and the motto "Labore et constanta,” with the fixed point providing stability and the moving point doing the work. There is a small woodcut version on the title page of L’Obel’s herbal (third image), but we chose to enlarge a handsome engraved version from a book of classical portraits written by Johann Faber and Theodor Galle in 1606 and published by the Plantin-Moretus Press (first image).

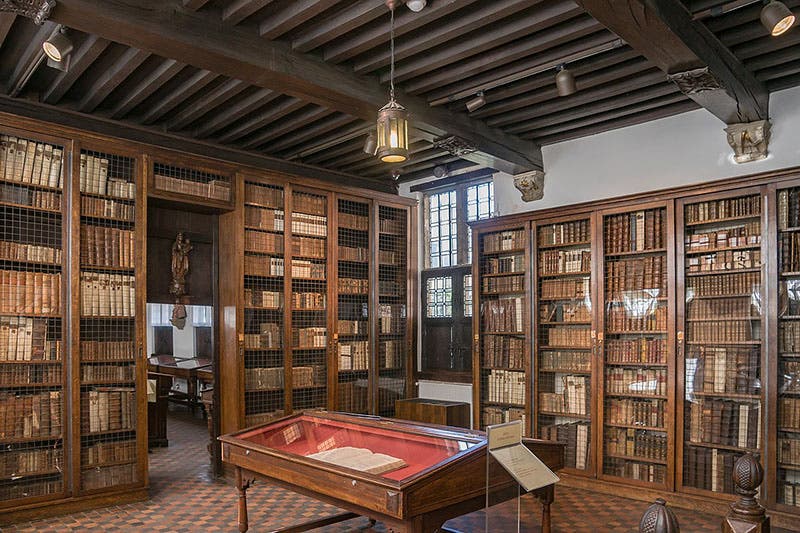

The Plantin-Moretus Press is renowned for another reason – they were in business for a long time, and they kept everything. When the press broke up in the late 19th century, it was quickly (and wisely) decided to turn the centuries-old building and its contents into a museum, the Plantin-Moretus Museum, the most important printing museum in the world. If you want to see Rubens' sketches for Aguilon's book on optics, you can find them in the museum archives, as well as the copper plates, proof strikes, and all the relevant correspondence. There is also a library filled with Plantin-Moretus imprints and author manuscripts, and a room displaying original 16th-century presses and type cases. If you are ever in Antwerp and you like books, you should visit.

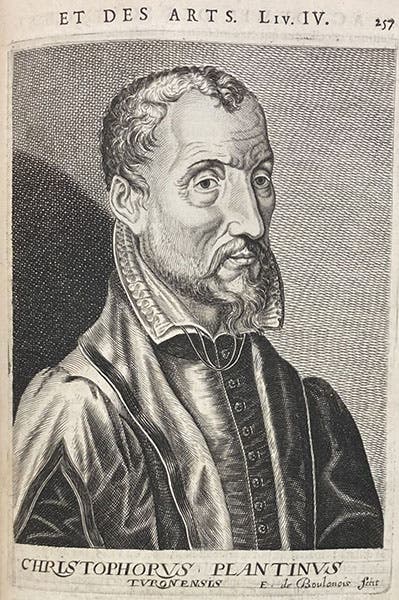

It is nice that we have an engraved portrait of Christophe Plantin, but the Plantin-Moretus Museum has a much finer one, painted posthumously by Rubens in 1612. We show it as our final image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.