Scientist of the Day - Frank J. Sprague

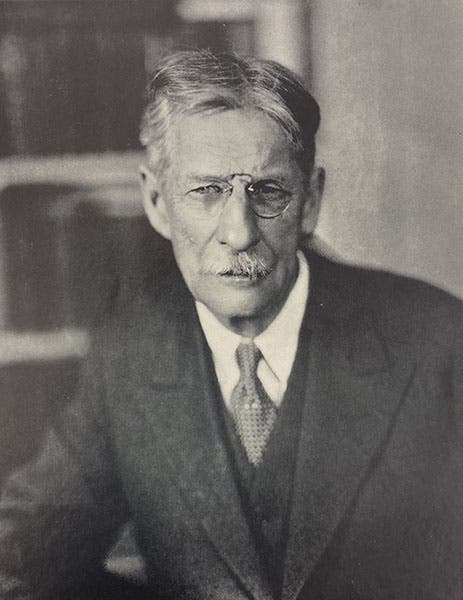

Frank Julian Sprague, an American electrical engineer, was born in Gilford, Conn., on July 25, 1857. He is renowned as the principal architect of electric traction in this country. He attended the U.S. Naval academy in Annapolis and served a few years before resigning to work for Thomas Edison. Sprague's passion was motors, while Edison's was lighting, so they made a good pair.

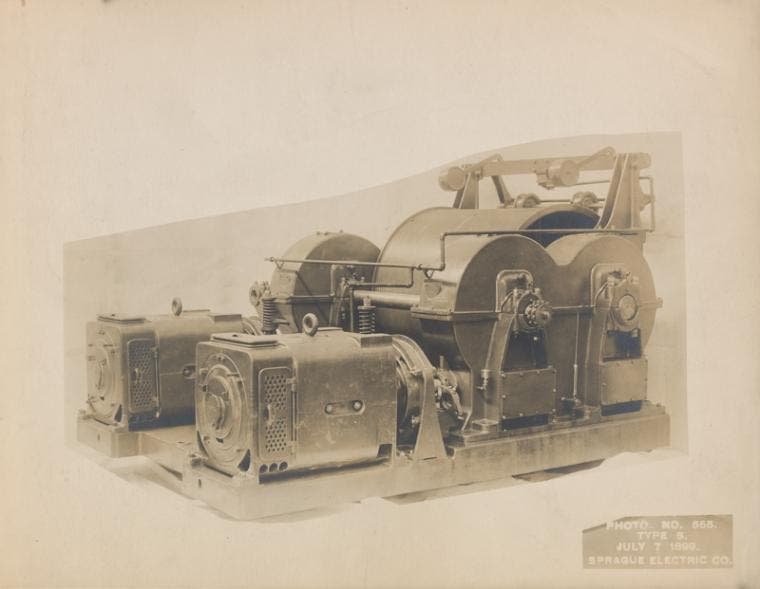

In 1884, Sprague invented a new electric motor that was brushless (and so did not spark) and provided constant speed, no matter the load. It was just the thing to power an electric streetcar. But there were no self-powered electric streetcars in the U.S. So Sprague set out to create a market. He resigned from Edison's company and set up his own. By 1888, he was ready to supply a willing city with a complete electric streetcar system. That lucky municipality was Richmond, Viginia, which now had the first electric railway anywhere, and it tolled a death knell for the cable car, everywhere except San Francisco, and for horse-drawn streetcars.

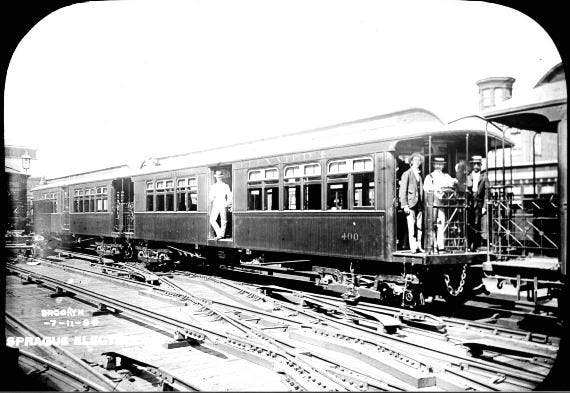

Soon Sprague was supplying electric railway cars for the Chicago elevated system, and for networks in Brooklyn nd Boston. One of the original cars for Chicago's El, put in service in 1892, is on display in the Chicago History Museum (fourth image). Most of Sprague’s streetcars received power through a trolley pole riding under overhead power lines. Sprague did not invent the trolley pole, but he certainly improved it. Sprague even helped Boson go underground, with a third rail system.

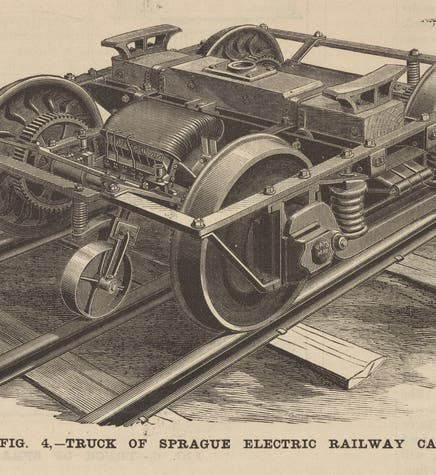

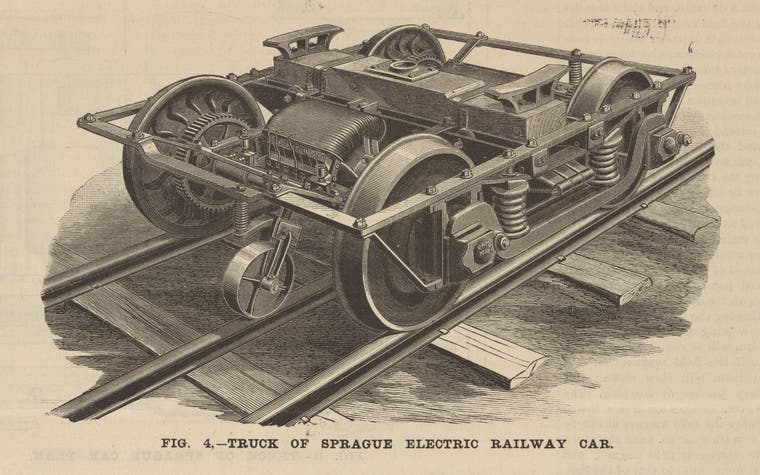

One of the key features that made an electric railway possible was another Sprague invention, the M-U or multiple unit system, where each car had its own powered truck, and a train of cars had a single set of controls. That was the final breakthrough, achieved by 1898, and soon electric streetcars were everywhere.

Sprague soon turned his attention to "vertical" electric transportation – elevators – and had just as much success there. The major obstacle was designing a motor that was powerful yet would fit in a small space, and Sprague did just that. His motors were amazingly compact for the horsepower they produced. Before his company was bought out by Otis Elevator Co., he had actually figured out a way to run express and local elevators in the same shaft! The skyscraper would have been impossible without an efficient electrically powered elevator system.

After Sprague's death in 1943, his wife deposited most of his papers in the New York Public Library, portions of which have been digitized. We drew on this collection for several of our images here. Later, before her own death, she endowed the Sprague Building at the Shore Line Trolley Museum in East Haven, Conn., and gave them a number of artifacts as well, including an original Sprague traction motor of 1884, the oldest Spague motor in existence. I don’t know what other Sprague items they have, but as the only trolley museum in the country, it might be well worth a visit.

We have no books by Sprague – I am not sure he wrote any – but we do have a nice short bio-tribute from the 1950s, Frank Julian Sprague, Father of Electric Traction, 1857-1934, by Passer, Harold (1952), which contains a friendly and not often seen photo of Sprague, which we used as our second image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.