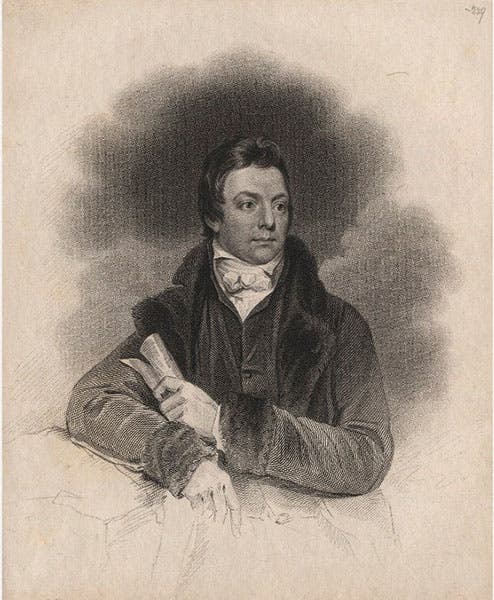

Scientist of the Day - Henry Salt

Henry Salt, an English artist, secretary, diplomat, and collector of antiquities, died Oct. 30, 1827, at the age of 47. He was born in Lichfield in 1780 and studied to become a portrait painter, but never made the grade, although he had artistic talent. In 1802, he was hired by George Annesley, Viscount Valentia, to accompany him on a trip to India via the Cape of Good Hope and the Middle East. Valentia planned to write a book about his travels, and Salt was probably chosen as his aide and secretary because he could draw. Valentia would publish his book in 1809, and it was illustrated with views by Salt. Salt even published his own book, 24 Views, with sketches that Annesley did not use.

Salt must have shown considerable ability as an aide, because the viscount sent him on several diplomatic missions to Abyssinia and Egypt; in Egypt, he met the new pasha, Muhammad Ali, and the two apparently hit it off. After they returned to England, the foreign office must have heard about Salt’s diplomatic skills, and about the welcome he received from Ali, for in 1816, Salt was back in Cairo, as the British consul to Egypt.

Before he left London, Salt met with Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, and also a Trustee of the British Museum. The museum had added a new wing, the Townley Gallery, in 1808, to display antiquities, and two of the rooms were given over to the Egyptian antiquities (including the Rosetta stone) that the British had confiscated from the French when Napoleon's army in Egypt was defeated in 1801. Banks apparently told Salt that the museum wanted more Egyptian artifacts and would pay for them, because as soon as Salt was settled in Cairo in 1816, he got to work.

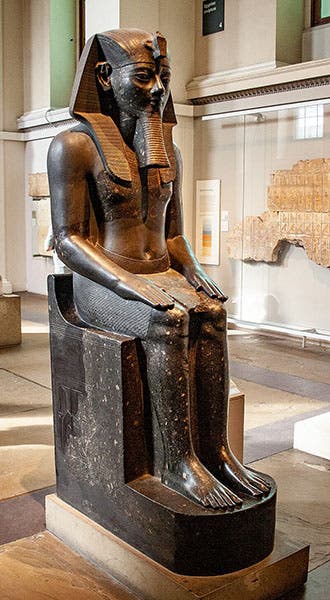

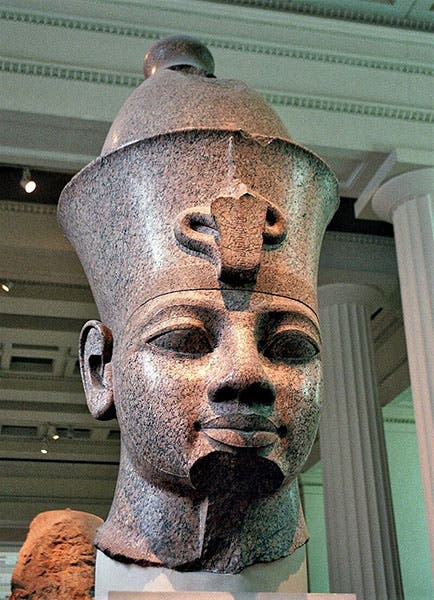

Salt heard that there was a monumental statue that had been toppled from its perch at what we now call the Ramesseum in the Valley of the Kings on the west side of the Nile at Thebes. Several enterprising scavengers had tried to retrieve it, but it weighed too much to move. Or so it was said. Salt met a former circus strongman now living in Cairo, Giovanni Belzoni, who agreed to take on the task of transporting the head and torso of what was variously called Ozymandias or the Younger Memnon to Cairo. Belzoni was successful, amazingly, and Salt and Johann Ludwig Burckhardt bought it, and they gave it to the British Museum in 1817. It arrived in London in 1818, and went on display in the Townley Gallery in 1819. We told the story in a post on Belzoni, and also in a post on Percy Bysshe Shelley, whose poem Ozymandias was supposedly inspired by the Younger Memnon.

Salt continued to collect all sorts of Egyptiana, ranging from other monumental heads and busts to funerary shabti and papyri, with the full permission of Pascha Ali to send them to London. By 1820, he had a fine collection, which he valued at £5000, ready to sell to the trustees. But Banks had died, and no one else at the museum really liked Egyptian art (compared to Greek and Roman art), and they offered only £2000 for the lot. Salt was saddened by the low offer, and no doubt somewhat embittered, for there were some glorious pieces in this first collection, including three or four monumental heads and busts of Amenhotep III. But he accepted the payment, and you can now see many works from his collection on display in the Museum, and here in this post.

Salt immediately began a second collection and offered it for sale, and when the museum tried to lowball him again, he sold the lot to France for £10000 pounds, and then started a third collection. He died of an ailment unknown to me in 1827, and his third collection was bought by the British Museum from his estate.

It is easy in modern times to deplore the actions of Salt and Belzoni in robbing Egypt of the artifacts of her golden Age, but the fact was, no one in Egypt at the time wanted any of it, not the ruling class, nor the working class, and everyone seems to have regarded the carved heads, animals, and scarabs as junk to be discarded. There were a few contemporary protests when Lord Elgin robbed the Parthenon of its frieze (the Elgin marbles came into the British Museum in 1816, just before the Younger Memnon). But absolutely no one, in Egypt or in England, objected to what Salt was doing. So when you visit the Egyptian rooms at the British Museum, most of what you see, other than the Rosetta stone and a few other Napoleonic items, was collected by Henry Salt. The man not only had good connections, he had excellent taste.

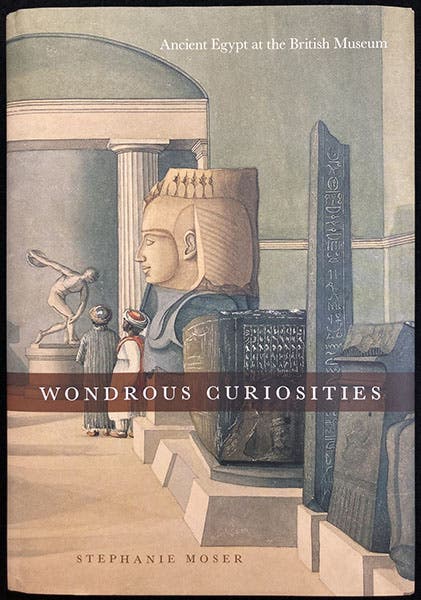

Dust jacket, Wondrous Curiosities: Ancient Egypt at the British Museum, by Stephanie Moser, University of Chicago Press, 2006, detail of a watercolor in the British Museum, dated 1819, with the Younger Memnon in the center (author’s copy)

An excellent book on the growth of the Egyptian collection at the British museum is Stephanie Moser's Wondrous Curiosities: Ancient Egypt at the British Museum (University of Chicago Press, 2006). The dust jacket (last image) shows a detail of a watercolor in the Museum's collection, which depicts one of the Egyptian rooms, and there, right in the center, is the Younger Memnon, unmistakable with its red granite head and gray granodiorite torso. The watercolor is dated 1820, and it says it was based on a sketch made on the spot in September 1819. The Museum and Wikipedia and everyone else state that the Younger Memnon did not go on display until 1821, and I used that date in my posts on Belzoni and Shelley. Clearly Memnon was in the Townley gallery and viewable by the public in 1819 – still not in time for Shelley to have seen it before he wrote Ozymandias, but closer. I cannot decide if I should go back and correct the earlier posts, or just refer readers to this one. I will probably do the latter. Altering historical documents should be done with caution, and only with full public disclosure.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.