Scientist of the Day - Jacques Cassini

Jacques Cassini, a French astronomer, died Apr. 16, 1756, at the age of 79. Jacques was the son of Giovanni Domenico Cassini, a Bolognese astronomer who came to Paris in 1669 at the request of King Louis XIV to work at the Paris Observatory, then being constructed. Giovanni promptly changed his name to Jean-Dominique and carved out a large astronomical niche in the next 40 years. He also started a dynasty.

Jacques was the second in a long reign of Cassinis, taking over as the semi-official Observatory director when his father died in 1712, and siring a son, César-François Cassini de Thury, and, indirectly, a grandson, another Jean-Dominique, but this one a comte de Cassini. All four presided over the Paris Observatory during a long tenure of 124 years. To simplify things, they are often referred to as Cassini I, II, III, and IV. Today's subject, Jacques, is Cassini II.

Cassini II was unfortunate, in that he was born in an era when many French astronomers were having a hard time giving up the vortical cosmos of their countryman, René Descartes, in favor of the gravitationally bound universe of the Englishman, Isaac Newton. One of the many things Cartesians and Newtonians disagreed about was the shape of the Earth. Cartesians believed the Earth is prolate, or lemon-shaped, while Newtonians, using proofs based on gravitational attraction, insisted it must be oblate (grapefruit-shaped), flattened at the poles. The only way to determine the shape empirically was to measure the length of a degree along a meridian of longitude at different latitudes.

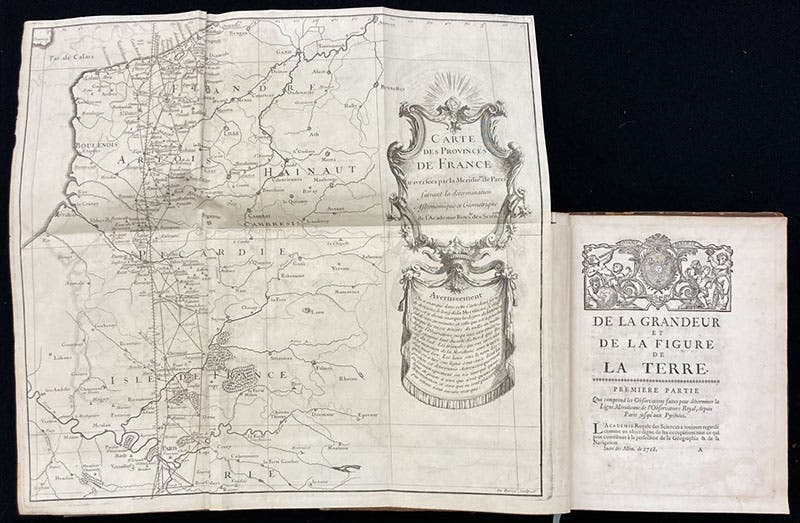

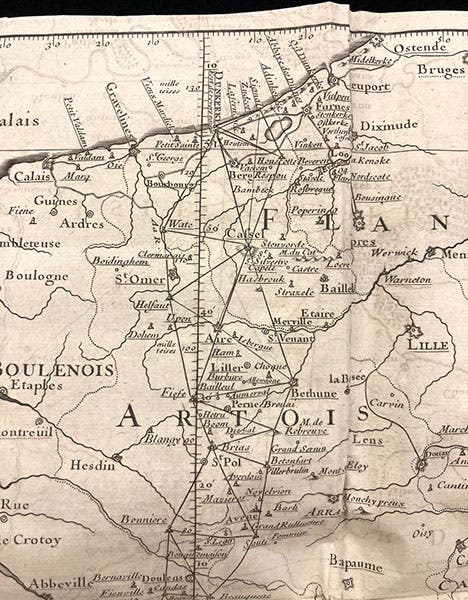

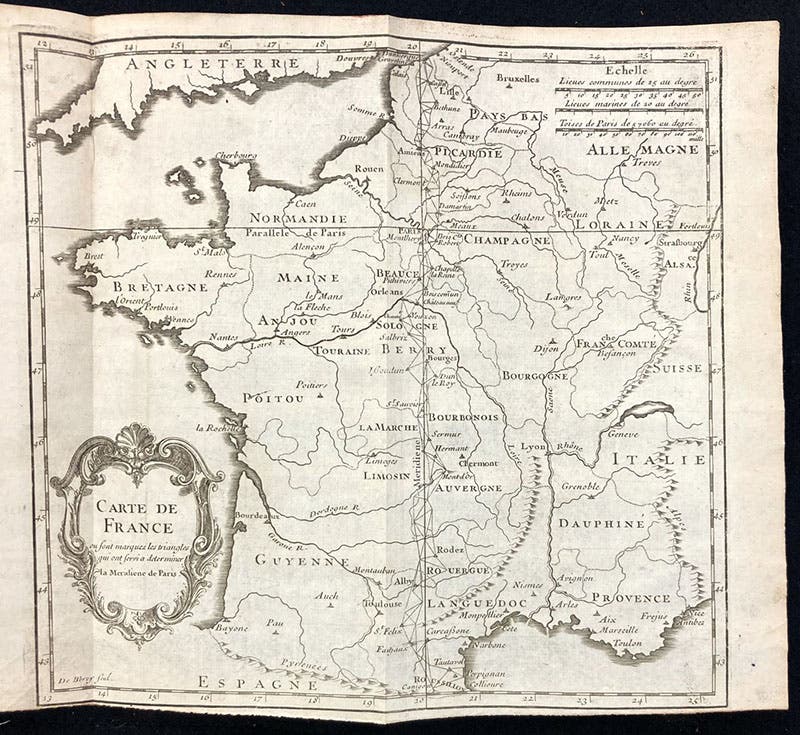

The French were old hands at this, Jean Picard having measured the length of a degree at the latitude of Paris in 1669-70. Cassini I continued the triangulations south toward the Mediterranean, and Cassini II did so northward to Dunkirk (third image), and he was convinced that the measurements revealed that the degrees were getting smaller as one went north, consistent with a prolate earth. He published a book in 1720 making that point, called De la grandeur et de la figure de la terre; it was part of the Suites des Mémoires of the Royal Academy of Science. We have this work in our collections – it is the source of images two through four. Jacques was apparently an excellent cartographer, and the map of France that he threw in at the end of Grandeur, though small, is state of the art (fourth image).

Unfortunately, Cassini II did not understand that the difference they were trying to measure was smaller than the margin of error of their instruments. The only way to make the differences larger was to go to the equator, or the Arctic circle. Younger French astronomers went to both places in the late 1730s and 1740s, and their measurements confirmed the oblate Earth of the Newtonians (for more on the French expeditions, see our posts on Charles-Marie de La Condamine and Abbé Réginald Outhier). Jacques could never accept that he had been wrong, and when his son Cassini III joined the Newtonian side in 1744, Jacques simply dropped out of the fray and did other things until his death.

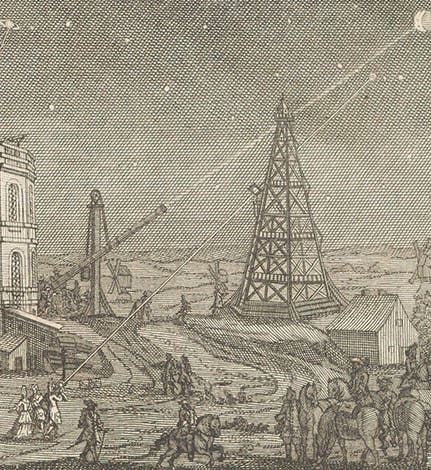

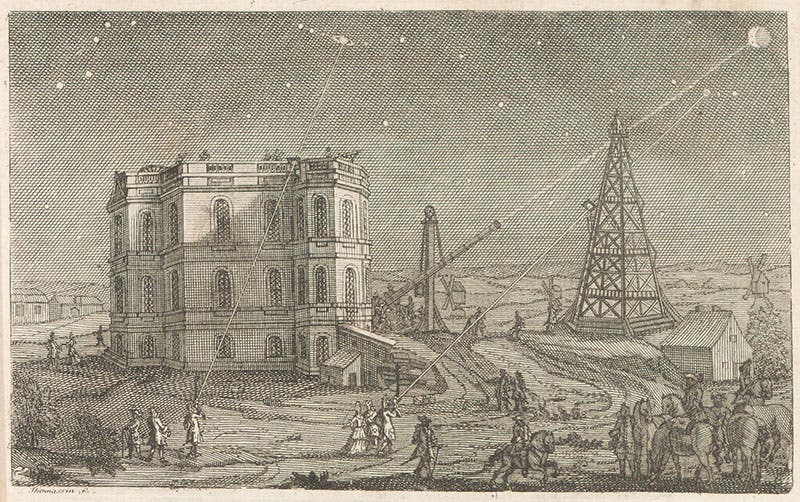

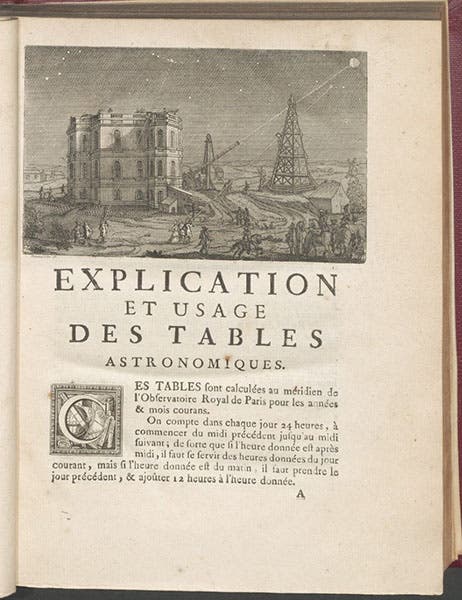

Cassini II published two other books, both in 1740, that did not address the problem of the shape of the earth; one was Élemens d'astronomie, essentially a fat textbook (fifth image), and the other was his Tables astronomiques (sixth image) . We have both in our collections. The latter is significant in an odd way, in that it has a headpiece on the first page of text, an engraving that provides one of the very few contemporary images of the Paris Observatory. We mentioned this just 2 weeks ago in a post on Pierre-Charles Le Monnier, who provided the other image of the Observatory of which I know, but it is not nearly as commanding as this one. It is often reproduced, but hardly ever in context, so we show both the full page (last image) and the enlarged vignette (first image).

A final oddity about Jacques Cassini is that he left no portrait behind. He was a wealthy and prominent man who married well and had an estate at Thury, and yet he apparently never commissioned a portrait. The engraving that is often shown as a portrait of Jacques (as on Wikipedia) is just a copy of a painting of his father, Giovanni Domenico. Jacques is still a faceless Cassini.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.