Scientist of the Day - John Westwyk

John Westwyk, an English monk and astronomical instrument maker, died sometime before 1400, probably in the infirmary at the Benedictine abbey of St. Albans, northeast of London. The Abbey, which was built largely of bricks and tiles gleaned from the nearby Roman city of Verulamium, was not far from the small village of Westwick, where John was born. He was probably educated at the abbey school and became a monk around 1380. He spent some time at Tynemouth Priory, a subsidiary of St. Albans, where he left behind some astronomical books he had copied, originally written by Richard of Wallingford, St. Albans’ most famous abbot (and clock-maker). John also engaged in a crusade against the anti-pope, and returned alive, but in poor health.

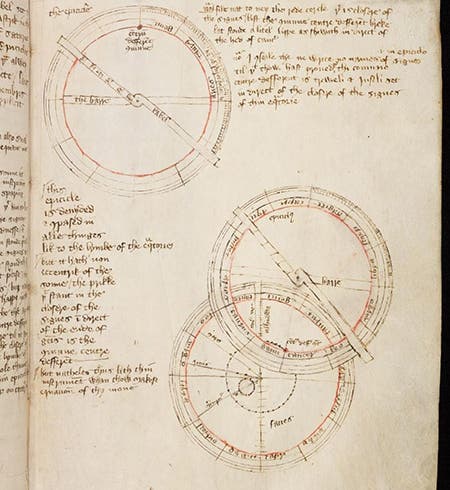

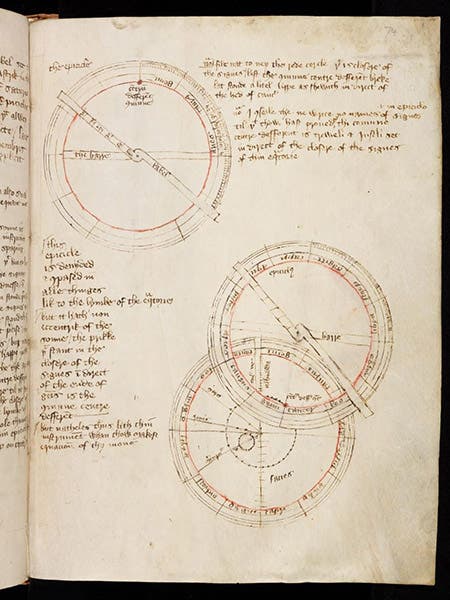

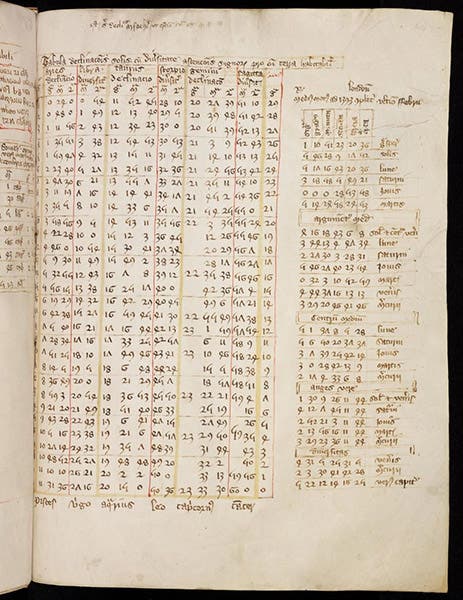

After his death, John lay amouldering in anonymity for over 600 years before he suddenly became famous, a least in a limited circle. It all started with Chaucer. In 1951, a young scholar named Derek Price found a medieval manuscript in the library of Peterhouse College at the University of Cambridge. The manuscript contained directions for building an instrument called an equatorium, which allowed one to calculate the positions of a superior planet (Mars, Jupiter, or Saturn), as well as Mercury and Venus. He called it, using a Middle English title, the Equatorie of the Planetis. Buried in the text, Price found the date 1392 and the name Chaucer. Geoffrey Chaucer, author of the Canterbury Tales, happened to have written a Treatise on the Astrolabe in 1391, which survives as one of the first pieces of medieval technical scientific literature written in English (albeit Middle English). Because Peterhouse Ms 75 seemed to be in the hand of its author (a correct surmise, as it turned out), Price thought he had discovered an unknown Chaucerian manuscript in the hand of Chaucer himself, and he announced his claim widely. It did not bring him any love at Cambridge, or among Chaucer scholars, but it did win him a job offer at Yale, where he had an illustrious career, expanding his name to Derek de Solla Price.

Unfortunately, for Price and for Chaucer, a Norwegian scholar named Kari Anne Rand Schmidt, in 1993, showed convincingly, using philological methods we cannot go into, that Peterhouse Ms 75 could not have been written by Chaucer, and therefore was not in the hand of Chaucer. Over 20 years later, in 2014, now writing as Kari Anne Rand, she announced that she had found a signed astronomical manuscript at Tynemouth that matched the handwriting of the Equatorie of the Planetis perfectly. The writer was John Westwyk. He had invented his own version of an equatorium, and provided tables and wrote the draft describing its use, that still survives at Peterhouse College Library.

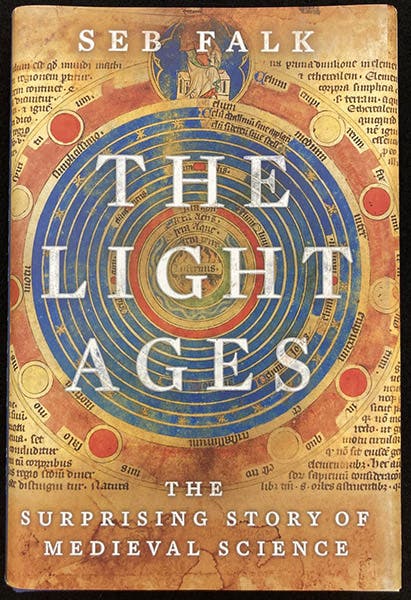

Dust jacket, The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science, by Seb Falk (New York: Norton, 2020). The American edition has a different subtitle, for a reason that cannot have been a good one (author’s copy)

I am guessing that the revelation that the Equatorie of the Plantis was designed and written by John Westwyk, and not Geoffrey Chaucer, is unlikely to change your life significantly, and I would probably not have made John the subject of a post, were it not for the fact that a Cambridge historian of science recently decided to make John Westwyk’s story the basis of a book, not about astronomical instruments, but about 14th-century culture and science, a book intended not for fellow historians, but for anyone with some intellectual curiosity. With a goal of showing that the Dark Ages were far from dark, the author called his book, The Light Ages: A Medieval Journey of Discovery (2020). The author is Seb Falk, and he did an excellent job of not only telling John’s story, but giving it a convincing setting in 14th-century England. Falk was also involved in helping create a replica of John’s equatorium for Peterhouse Library, which was then used to make a virtual operating model for the Peterhouse Library website. You can access it on this webpage. It works much better, at least for me, on a laptop rather than a smartphone. You can also learn a great deal more about the Equatorie of the Plantis at this same webpage.

We have in our collections Price’s 1955 book about the Equatorie, there attributed to Chaucer, as well as Rand Schmidt’s 1993 book, disproving the Chaucer connection, and also containing a complete facsimile and transcription of the manuscript and a concordance as well. We do not have her 2014 article assigning authorship to John Westwyk, which appeared in a philological journal to which we do not subscribe, but it is available online.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.