Scientist of the Day - Ptolemy of Alexandria

Ptolemy of Alexandria, sometimes referred to as Claudius Ptolemy, was the most accomplished and most influential astronomer of the ancient world, and he dominated the science until the mid-17th century. We have no idea when he was born or died, only that he lived in the second century of the Common Era. He was Greek and associated with the city of Alexandria. Ptolemy pretty much laid the groundwork for three sciences: astronomy, geography, and astrology. We will discuss today his contribution to astronomy, and save his book on mapping the Earth and his astrology for another occasion.

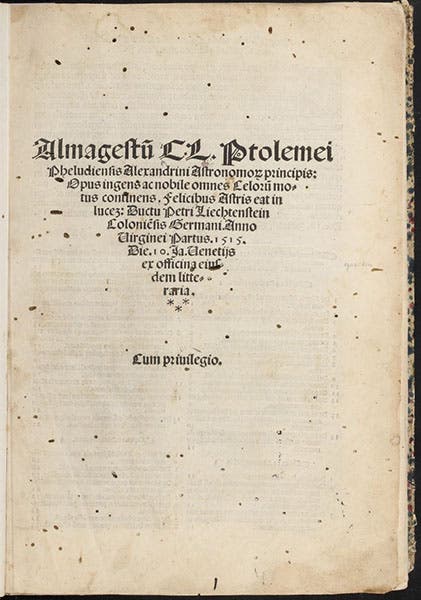

There were many accomplished Greek astronomers before Ptolemy (and many Babylonian astronomers before them), but Ptolemy stands out because he wrote a complete treatise on the principles and techniques of astronomy, and that treatise survived to be translated into Arabic and Latin and shape the course of medieval and Renaissance astronomy. Ptolemy's book is often referred to as the Almagest, from an Arabic title meaning "the greatest," i.e., the largest of his astronomical treatises. Many scholars prefer to call it the Syntaxis, part of the original Greek title. In my school days, it was always the Almagest, and I continue to refer to it that way.

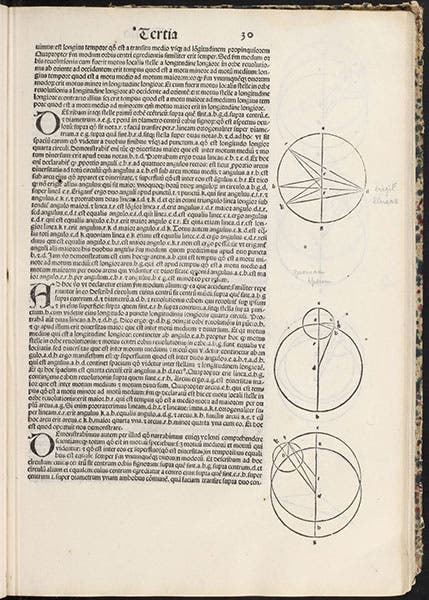

Ptolemy’s principal concern in the Almagest was to account for and predict the movements of the 7 heavenly bodies that the Greeks called "planets," which moved or wandered against the stars. This included the five visible planets out to Saturn plus Sun and Moon. Because Ptolemy assumed, as did nearly all ancient Greeks, that the 7 planets orbit a stationary central Earth, this was not easy to do. It required that the planets move on large circles, called epicycles, that in turn orbit the Earth on secondary circles called deferents. The epicycle-deferent system was different for each planet – Venus, which varies widely in magnitude, had a large epicycle that brought it close to, and then far from, the Earth, while Saturn, which changed little in brightness, had a small epicycle. In addition, Ptolemy complicated his models by putting the Earth slightly off center and by adopting other artificial centers of motion called equant points. The goal in all this fine tuning was to come up with models that predicted the motions of the planets to a fraction of a degree. Amazingly, Ptolemy was able to do this (amazing because the planets do not orbit the Earth), and so could any capable mathematician who had the Almagest in hand. Since Ptolemy included in his Almagest a catalogue of 1028 stars that did not wander, the book was a complete guide to the heavens.

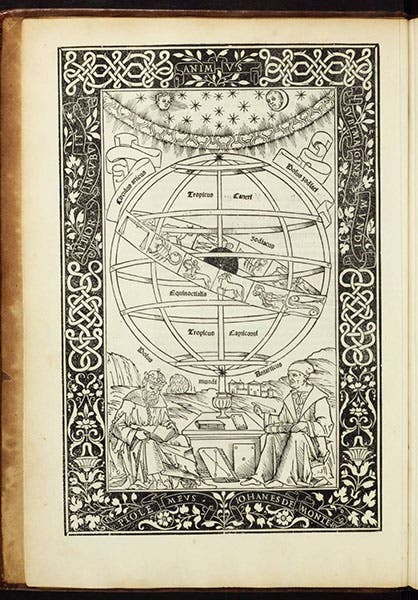

The Almagest was translated into Arabic during the Golden Age of Islam, and later, in the medieval West, into Latin, first from Arabic, and eventually from the original Greek, when Greek manuscripts became available in the Renaissance. Regiomontanus published an epitome of the Almagest in 1496, which served as an excellent introduction to Ptolemaic astronomy, and the Almagest itself was finally printed in 1515, late for a book of its importance, but it was a complicated book to print (fourth and fifth images). When Copernicus published his revolutionary book in 1543, proposing a heliocentric system of astronomy, it was the Almagest he was rebelling from, but only from the geocentricity of the models – he was fine with nearly everything else. Ptolemy’s epicycles and deferents would persist until the work of Johannes Kepler in the early 17h century.

The Almagest is a mathematical, not a cosmological, work, with two-dimensional models, so it would be easy to assume that the models were for computational purposes only, and were not intended to be real. But it is clear from another Ptolemaic work, the Planetary Hypotheses, in which he attempted to calculate the size of the universe, that Ptolemy did envision the cosmos as a nest of real three-dimensional epicycles and deferents. There were attempts in the early Renaissance, especially in the work of Georg Peurbach, to depict epicycles and deferents as solids, but usually only one planet at a time.

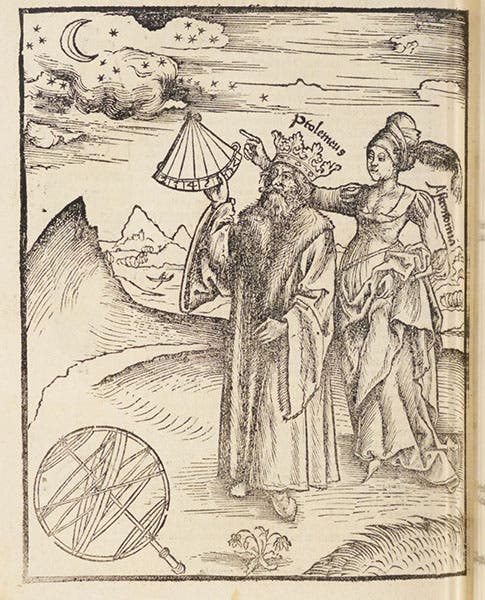

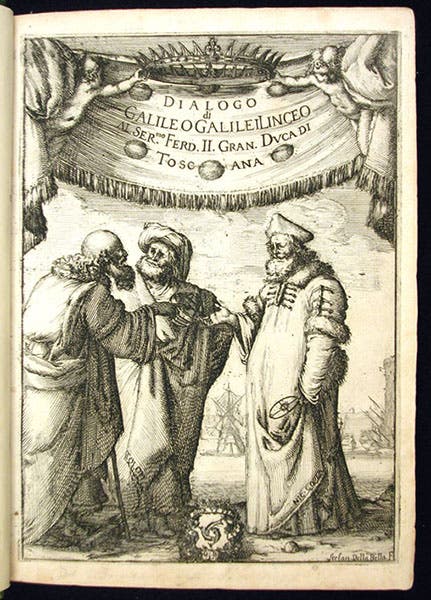

Since we have no idea what Ptolemy looked like, Renaissance portrait book editors could fashion Ptolemy's features as they wished. We show an engraving from Jean Jacques Boissard’s Icones (1597-99). But because he was such a famous astronomer, and a paragon of the Greek astronomical achievement, Ptolemy often appeared on the title pages and frontispieces of works by other authors. He was included on the woodcut frontispiece of Regiomontanus' Epitome of the Almagest (third image, at left; he wears a crown because he was often thought to be in the dynasty of kings that ruled Egypt), and he appeared in the section on astronomy in the Margarita Philosophica of Gregor Reisch (1503), again wearing a crown (second image). You can also find Ptolemy (with Aristotle) on the frontispiece to Galileo's Dialogo (1632; last image), and on that of Giambattista Riccioli's New Almagest (1651),

We have all the printed books mentioned above in our History of Science Collections, plus many more editions of the Almagest and Ptolemy’s other astronomical works, so plan to come here if you embark on a project that involves Ptolemy and/or the Almagest.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.