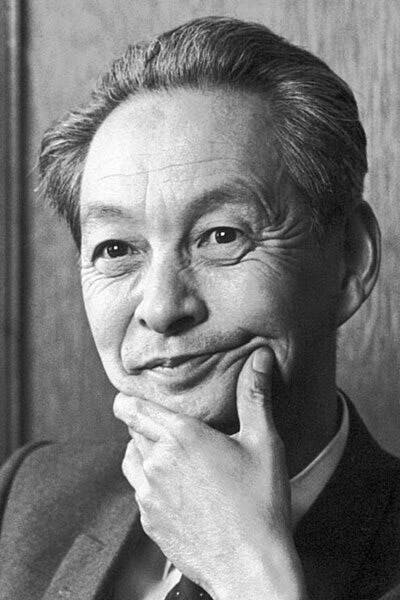

Scientist of the Day - Sin-itiro Tomonaga

Sin-itiro Tomonaga, a Japanese physicist, died on July 8, 1979, at the age of 73; he was born in Tokyo in 1906. He was a socially awkward and sickly child, but showed a real knack for scientific experiments, using equipment he built himself, such as electrolytic devices for generating hydrogen, or radio sets. After his father, a philosophy professor, got a job at Kyoto University, Tomonaga was able to enroll in the excellent high school there, where his grasp of science became apparent. At that school, he met and became friends with Hideki Yukawa, a year younger and equally enthused about relativity and, soon, quantum mechanics. It is odd that these two future Nobel Prize winners just happened to come out of the same high school physics class.

Tomonaga's major professor at Kyoto had studied at Cambridge, Copenhagen, and Heidelberg, three of the universities where the quantum revolution was forged in the 1920s, and beginning in 1929, he successfully persuaded Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and Paul Dirac to come to Tokyo to lecture and motivate his students. Tomonaga was especially taken by Dirac, who had formulated something called "quantum electrodynamics" (QED) in 1928. QED was the first attempt to combine quantum theory with special relativity. It was generally successful, in that it explained how electrons interact with light, and made many predictions later confirmed by experiments. In particular, it predicted something called the “fine-structure” of the hydrogen atom. But sometimes the “Dirac equation,” as one of Dirac’s constructs was called was called, generated solutions in the form of series which diverged to infinity, which was a problem.

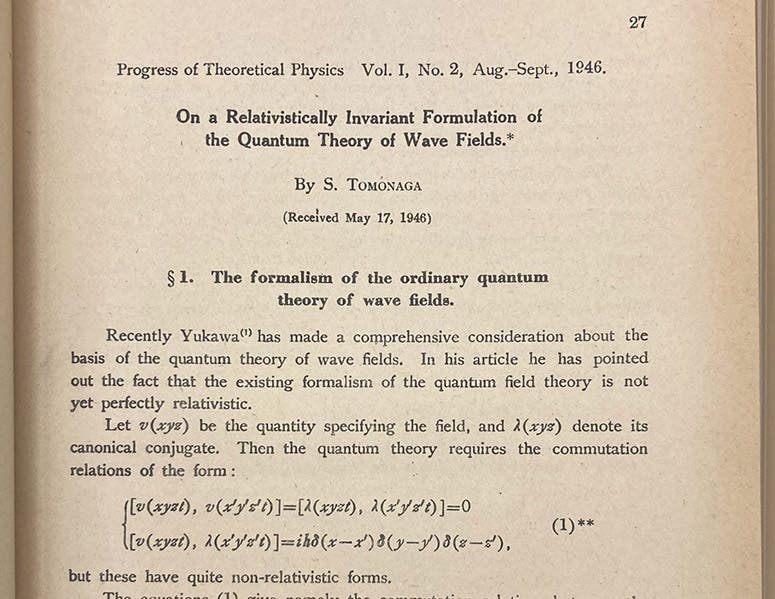

First paragraph, “On a relativistically invariant formulation of the quantum theory of wave fields,” by Sin-itiro Tomonaga, Progress of Theoretical Physics, vol. 1, p. 27, 1946 (Linda Hall Library)

Tomonaga worked on trying to get rid of the infinities, up to and into the war, with some success. He and a team of students even translated a Dirac textbook into Japanese in 1935. But by 1943, Tomonaga had been enlisted for war-related research, and when the war ended, he lost his home and suffered from severe food shortages. Nevertheless, he and his students were able to publish several papers in the English-language Tokyo journal, Progress of Theoretical Physics, founded in 1946. We happen to have a set in our library, printed on very low-quality paper, all they could get in Japan in 1946 and 1947 (second image).

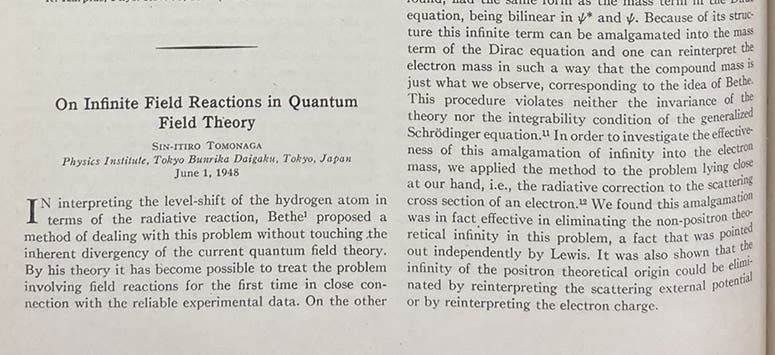

First paragraph, “On infinite field reactions in quantum field theory,” by Sin-itiro Tomonaga, Physical Review, vol. 74, p. 224, 1948 (Linda Hall Library)

Meanwhile, back in the United States, several dozen young quantum physicists convened in 1947 at Shelter Island, Long Island, for a conference organized by Robert Oppenheimer, to solve the problems of QED. They met again in the Poconos in 1948, and in Peekskill on the Hudson in 1949. Two of the brightest of these physicists, Julian Schwinger and Richard Feynman, independently, and using quite different methods, developed a process called “renormalization” that got rid of the infinities and made predictions that were accurate to a dozen decimal places. QED was now a complete success and everyone was pleased. But right after the Pocono conference, in April of 1948, Oppenheimer received a letter from Tomonaga, with some manuscripts and notes, and a few offprints; the letter provided an account of what he and his students had been up to regarding QED. Oppenheimer was amazed to discover that everything Schwinger and Feynman had done to cure the ailments of QED (except for the introduction of Feynman diagrams) had already been done by Tomonaga and his students under the most deplorable wartime and postwar conditions. Oppenheimer made copies of Tomonaga's letter and sent it to every participant at Pocono, and he arranged for Tomonaga to publish a short piece in Physical Review that same year (third image). Oppenheimer had been bothered by the smug superiority of American physicists, who thought the world revolved around their work, and he was happy to shift the spotlight to Japan. He was perhaps also feeling more than a little guilty that atomic bombs developed under his leadership had destroyed two of Japan’s cities.

Seventeen years later, in 1965, the Nobel prize in physics was awarded "for fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics," to Richard Feynman, Julian Schwinger, and Sin-itiro Tomonaga. To his credit, after a brief stint at the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton in 1949-51, invited there by Oppenheimer, Tomonaga chose not to stay in the United States, but returned to Japan and finished his career in Tokyo.

The second photograph was taken on the occasion of the award of the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics, which Tomonaga had to receive in Japan, due to injuries suffered in a recent fall.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.