Scientist of the Day - The Scopes trial ends

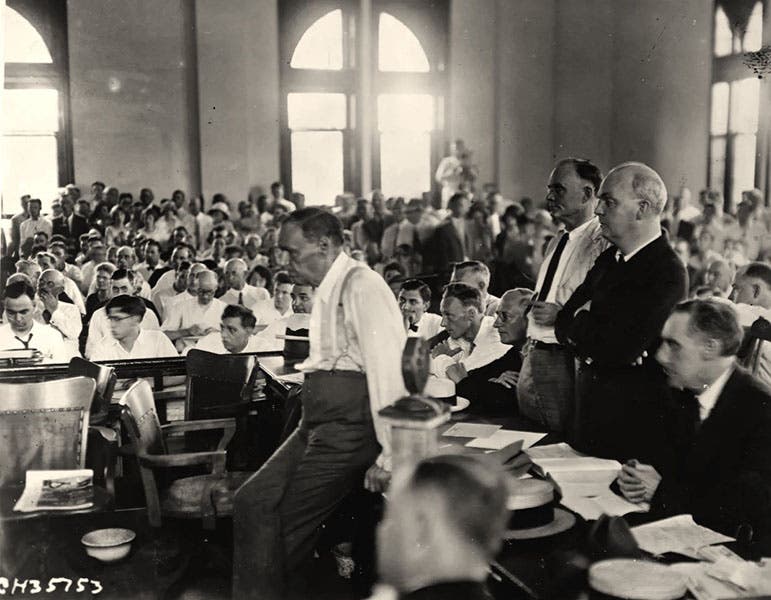

The Scopes trial hit its dramatic peak on the seventh day, Monday, July 20, 1925, when William Jennings Bryan, the special counsel for the prosecution, allowed himself to be examined by Clarence Darrow, the special counsel for the defense, on his knowledge of the Creation story related in Genesis. The encounter took place on a platform outside, on the courthouse lawn, because it was so hot inside. We told the story of this encounter in our first post on Bryan, back on July 20, 2021. We also commemorated the beginning of the Scopes trial just last week.

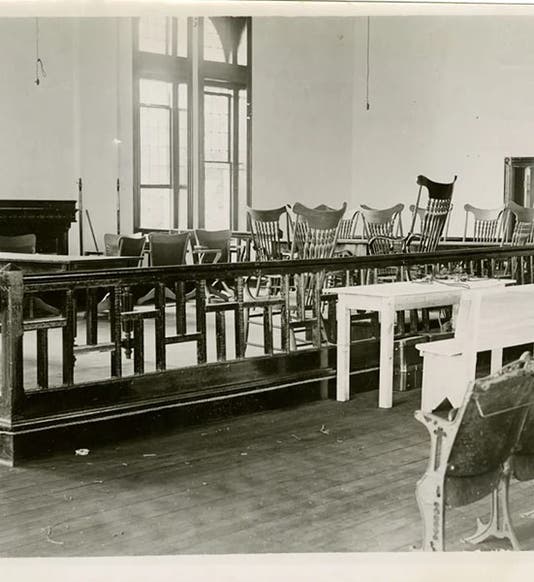

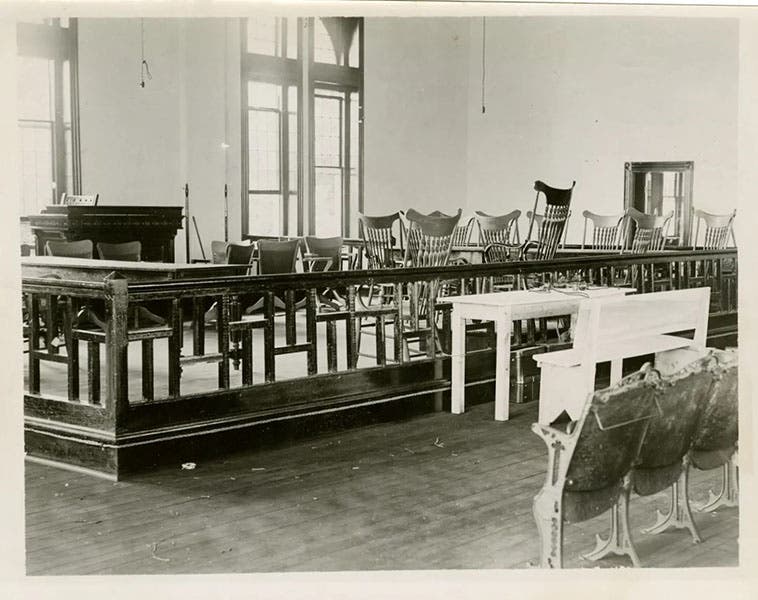

But by the next day, July 21, 1925, 100 years ago today, the drama of the cross-examination was gone, as if it had never happened, which, legally, it hadn't, as Judge Raulston expunged the entire confrontation of the previous day from the trial record. He ruled that the subject was not relevant to the question as to whether John Scopes had violated the Butler Act by teaching evolution in a Dayton, Tennessee classroom.

So Clarence Darrow threw in the towel and told the jury to bring in a verdict of guilty. That was really the goal of the ACLU all along, so they could challenge the legality of the Butler Act in a higher court. The jury did as instructed and found Scopes guilty, and Judge Raulston set the fine at $100 – the minimum possible under the law – and the Scopes trial was over. Five days later, as a first anticlimax, Bryan, suffering from diabetes, quietly died in his sleep. Six months after that, the Tennessee Court of Appeals set aside the verdict, pointing out that the jury should have set the fine, not the judge. The case was never retried, so it could not be appealed. The Butler Act stayed on the books.

What difference did it all make? Mississippi passed a similar anti-evolution law in 1926, and Arkansas followed in 1928, but every other state in which an anti-evolution bill was proposed, rejected it. Many publishers, fearful of a loss of revenue, removed the section on evolution from their biology textbooks (this happened, in fact, with the next edition of Hunter’s A Civic Biology, whose discussion of evolution provoked the wrath of Bryan at the Scopes trial; see our post of July 16, 2025). But evolution slowly crept back in; it was hard to teach biology without it.

In 1947, in the case of Everson vs. the Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court extended the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the states, declaring that no state may enact any laws that favor one religion over another. Twenty-one years later, in 1968, this ruling was applied in the case of Epperson vs. Arkansas to strike down the Arkansas law against teaching evolution. The previous year, Tennessee’s Butler Act had been finally repealed by the state.

There was a brief flurry of anti-evolution activity in the 1960s, lasting through the 1970s, when fundamentalists tried to argue that there was scientific evidence for creationism, and a few school boards in the South ruled that “creation science” should be taught alongside evolution, but in 1987, the Supreme Court ruled that creation science was not a science but a religion. When “intelligent design” was proposed as a science by creationists in the 1990s, it too was struck down by the Court as lacking any scientific credentials. Evolution was the last explanation left standing.

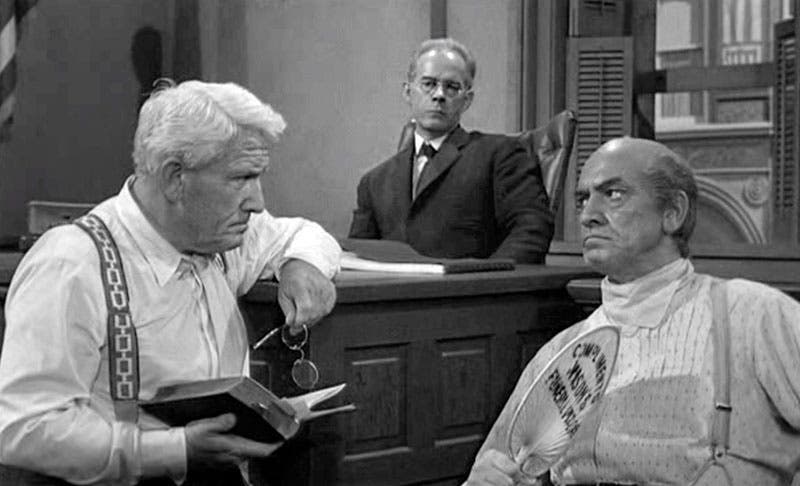

Perhaps the most constructive byproduct of the Scopes trial, other than alerting the Supreme Court to the dangers of state-supported religion, was that it inspired a play, and three films based on that play, called Inherit the Wind. I have not seen the play (1955), but I have seen all three film versions, multiple times. The first (1960) showcased Spencer Tracy as Clarence Darrow, Fredric March as Bryan, and Gene Kelly as a sardonic H.L. Mencken; the scene with Darrow questioning Bryan about Bible science was especially well done. Jason Robards made a pretty good Darrow himself in 1988, and George C. Scott was a wonderful Bryan in 1999. All are still available, at least on DVD, and some can be streamed. If the subject interests you, I recommend that you see them all, and if you have time for only one, cue up the 1960 movie with Spencer Tracy.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.